I’ll say this for director Denis Villeneuve–he knows where the bodies are buried. His last film, Prisoners (2013), uncovered a rotting corpse, reveled in details of missing and dead children, and tossed Hugh Jackman into a pit. If I want someone beaten up, ditto–over the course of two and a half hours, in between exhumations, Jackman punched a kidnapped Paul Dano into a twitching mass of hamburger.

I’ll say this for director Denis Villeneuve–he knows where the bodies are buried. His last film, Prisoners (2013), uncovered a rotting corpse, reveled in details of missing and dead children, and tossed Hugh Jackman into a pit. If I want someone beaten up, ditto–over the course of two and a half hours, in between exhumations, Jackman punched a kidnapped Paul Dano into a twitching mass of hamburger.

Villeneuve’s new film, Sicario, is a half-hour shorter, so it has to pack more in. It begins with FBI field agent Kate (Emily Blunt) discovering 42 cut-up corpses in a ramshackle house in Arizona, used by a Mexican cartel to stash drugs. (Or maybe it was 46; some are bisected, or trisected, making it hard to count.) Following the raid, Kate retches, a reaction many in the audience will share, not ten minutes in. Looking to do something about the flagrant creep of violence across the borderline, Kate agrees to join a task force, whose origins are opaque–maybe CIA, maybe something else. Her teammates are Matt (Josh Brolin, moving into the sorts of roles his No Country For Old Men co-star Tommy Lee Jones used to play), a bluff good ol’ boy who has Kate’s back except when she pokes too hard into the details of their mission, and the mysterious Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), who keeps to himself, except when Kate pokes too hard into the details of their mission.

Sicario (which means “assassin”) is best when it leaves the bodies and bloodshed behind to concentrate on the mundane details of tracking drug traffickers, the kind of routine agent work that Matt detests. It’s also the portion of the movie where Blunt, in full Clarice Starling mode, gets to exhibit a believably workaday bravado, alertly assembling clues and puffing on cigarette after cigarette as she realizes that little is what it seems as the team blithely storms into Mexico. But the screenplay, by actor and writer Taylor Sheridan (Sons of Anarchy), leaves Blunt high and dry as the smoke and mirrors are cleared away for a disappointingly simplistic denouement, as Sicario‘s lurid streak returns with a vengeance. My audience, having recovered from the initial shock, responded with scattered cackling and jeering as the movie went over the top, leapfrogging past all of Roger Deakins’ fancy, sun-blasted cinematography (the opposite of his rainy-day palette for Prisoners) and the fashionably doomy score, by Prisoners and Theory of Everything composer Johann Johannsson. All that hard work by Academy Award alumni, all that tell-it-like-it-is “realism,” squandered on what amounts to a dumpster dive.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the miseries of the drug war in Mexico; each week brings fresh outrages of street violence and backroom corruption. But it’s very easy to exploit them. The Mexican characters in Sicario are ciphers–assassins, dealers, or innocents, their hands helplessly soiled, stuck in the middle of a worsening situation. The movie pays lip service to the suffering of citizens, with many a glumly beautiful composition of ordinary folk struggling to find normalcy as gunfire erupts anew.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the miseries of the drug war in Mexico; each week brings fresh outrages of street violence and backroom corruption. But it’s very easy to exploit them. The Mexican characters in Sicario are ciphers–assassins, dealers, or innocents, their hands helplessly soiled, stuck in the middle of a worsening situation. The movie pays lip service to the suffering of citizens, with many a glumly beautiful composition of ordinary folk struggling to find normalcy as gunfire erupts anew.

Sicario concludes several minutes earlier than it does. One character tells another, “Move to a small town…this is a land of wolves now,” in the confident tone of a conspiracy-minded Trump supporter. The takeaway is: “The drug war is beyond governments and civilians now. Leave it to agents outside the law and forget about it.” With small-town America riven with drug violence, and plenty of snacking wolves to contend on this side of Trump’s mythic wall, yeah, that’s a great idea. Sicario is a small-minded, harebrained movie, a Charles Bronson revenge flick draped in the ecclesiastical garb of the fall season “prestige” film. And an insult to Bronson, whose movies always cut to the chase, minus the bullshit.

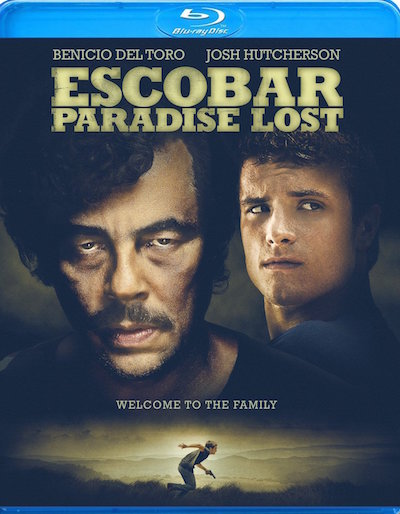

Benicio Del Toro’s role in Sicario can’t help but recall his Oscar-winning turn in Traffic (2000), with a few pounds and 15 years of descent into the abyss of drug warfare packed on. Or his henchman part in the Bond entry Licence to Kill (1989), or, for that matter, The Wolfman (2010), where he loved and menaced Blunt. In Escobar: Paradise Lost, on DVD and Blu-ray Oct. 6, he brings it all together, as the notorious Pablo Escobar, kingpin of Colombia’s Medellin Cartel, who loves his niece, prays with his mother, and has his enemies whacked before breakfast, usually when wearing sweaty tracksuits.

Benicio Del Toro’s role in Sicario can’t help but recall his Oscar-winning turn in Traffic (2000), with a few pounds and 15 years of descent into the abyss of drug warfare packed on. Or his henchman part in the Bond entry Licence to Kill (1989), or, for that matter, The Wolfman (2010), where he loved and menaced Blunt. In Escobar: Paradise Lost, on DVD and Blu-ray Oct. 6, he brings it all together, as the notorious Pablo Escobar, kingpin of Colombia’s Medellin Cartel, who loves his niece, prays with his mother, and has his enemies whacked before breakfast, usually when wearing sweaty tracksuits.

Loosely based on a true story, the film co-stars Josh Hutcherson (The Hunger Games) as Nick, who has moved to Colombia to set up a surf camp with his brother Dylan (Brady Corbet). It begins toward its end, in 1991, as Nick has some time to ponder the wisdom of this not-so-bright decision while he tries to put off killing an Escobar underling, a hit ordered by the boss. “You’re family now,” says Escobar, as Nick indeed is–he’s fallen hard for his pretty niece, Maria (Claudia Traisac), who is proud of her uncle’s position as a “cocaine exporter,” one who gives back to the country’s poor with the billions in proceeds. In the film’s best, weirdly picturesque scenes, Nick and Maria hang out at one of Escobar’s haciendas, in countryside barren except for the compound and swimming pool. There the kingpin dines with solid gold utensils, real elephants roam amongst fake dinosaur statues, and the druglord’s hired guns laze around waiting for orders–which include offing some thugs who prey upon Nick and Dylan. This rather changes the meaning of “family,” and puts an unwitting Nick in Escobar’s debt, which must be paid in blood that the callow Canadian is unwilling to shed.

Other than Entourage‘s amusing movie-within-the-show, the Escobar story hasn’t been told on the big screen, though Oliver Stone and Joe Carnahan (Narc) made stillborn attempts. It still hasn’t. Escobar: Paradise Lost is mostly the uninteresting Nick’s story, with Del Toro making occasional appearances. (Note to filmmakers, not for the first time: Drop the pallid “audience identification” figures and just get to it.) They’re effective–Escobar, as hirsute as the actor’s werewolf, has a sleepy charm before baring fangs–but limited, in this indulgently long account, a feature debut by actor (Eat Pray Love), writer, and director Andrea Di Stefano. You binge-watch Netflix’s Narcos, which focuses on the hunt for Escobar; you slog through these two hours, and wonder how dense Peeta can be.

The disc does sport a good, half-hour making-of, with Di Stefano and the crew detailing the shoot in Panama. Del Toro, wearing a Cure “Disintegration” T-shirt, is heard from, loose and relaxed, and you marvel at the seeming ease with which he becomes the deadly Escobar, and the wily Alejandro. He owns these sorts of roles, but maybe they own him, too, and we underrate his considerable talent. There’s more to him than these Latino bogeymen.

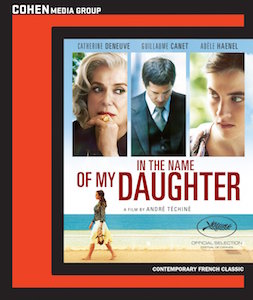

And now for something completely, sort of, different. After the horrors of Mexico and Colombia, Nice, the setting of In the Name of My Daughter, holds out promise for something more soothing. But don’t get too comfortable–director Andre Technine is a veteran disrupter of French cinema, and here he’s reunited with his partner in cinematic crime, the great ice queen Catherine Deneuve (they go back 35 years, and I saw them both onstage at the New York Film Festival in 1996, when their film Thieves was presented). Their latest movie recreates a sensational court case that riveted the nation in the 70s, and continues to reverberate. (The latest development came just last year.)

And now for something completely, sort of, different. After the horrors of Mexico and Colombia, Nice, the setting of In the Name of My Daughter, holds out promise for something more soothing. But don’t get too comfortable–director Andre Technine is a veteran disrupter of French cinema, and here he’s reunited with his partner in cinematic crime, the great ice queen Catherine Deneuve (they go back 35 years, and I saw them both onstage at the New York Film Festival in 1996, when their film Thieves was presented). Their latest movie recreates a sensational court case that riveted the nation in the 70s, and continues to reverberate. (The latest development came just last year.)

Deneuve, as unknowably beautiful as always, plays Renee Le Roux, a well-to-do widow trying to gain control of her deceased husband’s casino in the South of France. Her daughter, Agnes (AdÁ¨le Haenel), casts the deciding vote in her favor, but this is one of the few cases where they ally. Renee, for one thing, won’t give Agnes her share of her father’s inheritance. This may not be the worst thing, as a handsome ladies’ man, Maurice (Guillaume Canet), has been nosing around Agnes. Renee takes him for a fortune hunter, and in subsequent developments Agnes and Maurice, who has mafia ties, deprive her of her fortune. But money fails to buy happiness, and when Agnes disappears under baffling circumstances, Renee spends decades trying to bring Maurice to justice. But is he guilty?

Except for Haenel, a Cesar-winning actress who gives great despair in depicting Agnes’ torments, the mood here is of understatement, and a quiet willfulness as Renee moves through the courts, seeking justice that may never provide true closure, given past tensions. The film is beautifully crafted and acted, providing an unshowy showcase for its star and also Canet, who knows the territory well (he directed the hit thriller Tell No One). The Cohen Media Group Blu-ray shimmers–all those lovely surfaces, reeking of avarice and deceit beneath. (Techine could show Villeneuve a thing or two about burying bodies, literally and metaphorically). Extras are the film’s trailer and a Q&A with Canet, but the main attraction here is a haunting true story, well told.

Comments