Ah, spring break. Remember those magical weeks of cheap drugs, plentiful booze, and abundant sex? Well, I don’t; in college 30 (sigh) years ago I’d fly from thawing Chicago to somewhat less frigid New Jersey and home, usually with course-related reading material in tow.

Ah, spring break. Remember those magical weeks of cheap drugs, plentiful booze, and abundant sex? Well, I don’t; in college 30 (sigh) years ago I’d fly from thawing Chicago to somewhat less frigid New Jersey and home, usually with course-related reading material in tow.

Turns out Harmony Korine, the aging enfant terrible of American indie cinema (40, sigh), didn’t either. So he’s made up a movie about the annual ritual, Spring Breakers, which gave me a tingle as I settled in with both my tykes this spring break. (Times have changed.) Oh, those mischievous, lascivious Disney princesses, drawing penises, rubbing against one another, peeing through their bikini bottoms, and miming oral sex with beer-filled hoses and automatic weapons. Good times, ladies.

I also dozed off, more than once. Languid style, Skrillex-devised electronica paced to match arty editing rhythms, and an air of purposelessness will do that to an old horndog. I don’t think Korine will mind. Go with it, find your level, even in your dreams, I can hear him saying. As a critic I should compare Spring Breakers with the rest of his oeuvre, including Trash Humpers (2009) and Julien Donkey-Boy (1999), but as a moviegoer I must admit to seeing only his directorial debut, Gummo (1997), and calling it a day. Spring Breakers won’t have me going back to those gems I might have missed, but it is mildly diverting, if far less shocking to the system than Kids (1995) or Ken Park (2002), his screenplays for Larry Clark.

Not that there aren’t a few jolts along the way to the Florida coast. “It makes my tits grow!” enthuses one of the breakers early on as she slathers herself in cash obtained via a water pistol robbery of a local bistro. It may have been Ashley Benson (Pretty Little Liars); it may have been Vanessa Hudgens (High School Musical), I can’t recall, as they merged Persona-like in the soft swirl of Benoit Debie’s camera. (Selena Gomez, as a slightly lapsed Christian, and Rachel Korine, Harmony’s pop-topping spouse, round out the quartet.) Debie has shot films for the distasteful Gaspar Noe (Irreversible), who would have punished them and us for any transgressions. But Korine sends them down to St. Pete with a single, oft-repeated observation (“It’s like a videogame! It’s like a movie!”) and gets them into further trouble with the cornrowed Alien (James Franco), a drug dealer whose spiel (“Look at my shit!”) livens things up. Trying hard to outwigga Gary Oldman in True Romance, Franco is more comfortable here fellating a gun than he is talking with a monkey in Oz, and the movie dovetails nicely with his own less seen indie doodles. Clad in UV gear the girls go to war with a rival chieftain (rapper Gucci Mane, who bares more than any of his costars), which makes the proceedings sound more suspenseful than they are. I checked a summary and found I missed nothing during my own breaks.

Not that there aren’t a few jolts along the way to the Florida coast. “It makes my tits grow!” enthuses one of the breakers early on as she slathers herself in cash obtained via a water pistol robbery of a local bistro. It may have been Ashley Benson (Pretty Little Liars); it may have been Vanessa Hudgens (High School Musical), I can’t recall, as they merged Persona-like in the soft swirl of Benoit Debie’s camera. (Selena Gomez, as a slightly lapsed Christian, and Rachel Korine, Harmony’s pop-topping spouse, round out the quartet.) Debie has shot films for the distasteful Gaspar Noe (Irreversible), who would have punished them and us for any transgressions. But Korine sends them down to St. Pete with a single, oft-repeated observation (“It’s like a videogame! It’s like a movie!”) and gets them into further trouble with the cornrowed Alien (James Franco), a drug dealer whose spiel (“Look at my shit!”) livens things up. Trying hard to outwigga Gary Oldman in True Romance, Franco is more comfortable here fellating a gun than he is talking with a monkey in Oz, and the movie dovetails nicely with his own less seen indie doodles. Clad in UV gear the girls go to war with a rival chieftain (rapper Gucci Mane, who bares more than any of his costars), which makes the proceedings sound more suspenseful than they are. I checked a summary and found I missed nothing during my own breaks.

Still, absent the pulchritude of Russ Meyer, the pace of Roger Corman, or the more strident weirdness of Gregg Araki (Nowhere), Spring Breakers has a certain hard-to-define something that makes it watchable, when you’re prone enough to watch. Amidst the dullness of the competition its passage through malls has made for a minor spectacle, one that’s left the critics at a loss for words. It’s a fever dream.

Preoccupied as I’ve been with my toddlers gone wild this spring break I’ve struggled to keep up with the current cinema. Still playing is the Oscar-nominated documentary The Gatekeepers, in which the six men who have run the Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence agency, talk about their time at the helm, amidst continual upheaval. Directed Fog of War-style by Dror Moheh, focused solely on each chief, the film is riveting, if blinkered by the absence of outside critique. But it commands attention, like having several seasons of 24 or Homeland pull up a chair and talk to you.

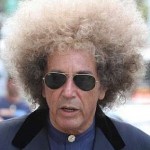

David Mamet’s HBO docudrama Phil Spector is a case of aggravated assault. Its veracity completely demolished, you have to wonder what Mamet was up to in an extremely partial view of the impresario’s mistrial for the murder of Lana Clarkson, for which he was found guilty in a subsequent proceeding. All I can think of is that Mamet sees in Spector a fellow artist whose celebrity and influence are waning, who deserves to be a cut a break by us naysayers and nobodies, the little people who lapped up his hit singles when he was on top. I call bullshit. The filmmaking, however, is pure Mamet, taut and lean, with Al Pacino (repurposing his eccentric stage characterization as Herod in Salome) and attorney Helen Mirren (whose motivations are inexplicable as portrayed) laying on the ham. A final scene involving the infamous “Hendrix wig” is suspenseful, humorous, and with a certain pathos, but like the hairpiece there’s very little underneath the irritating Phil Spector.

David Mamet’s HBO docudrama Phil Spector is a case of aggravated assault. Its veracity completely demolished, you have to wonder what Mamet was up to in an extremely partial view of the impresario’s mistrial for the murder of Lana Clarkson, for which he was found guilty in a subsequent proceeding. All I can think of is that Mamet sees in Spector a fellow artist whose celebrity and influence are waning, who deserves to be a cut a break by us naysayers and nobodies, the little people who lapped up his hit singles when he was on top. I call bullshit. The filmmaking, however, is pure Mamet, taut and lean, with Al Pacino (repurposing his eccentric stage characterization as Herod in Salome) and attorney Helen Mirren (whose motivations are inexplicable as portrayed) laying on the ham. A final scene involving the infamous “Hendrix wig” is suspenseful, humorous, and with a certain pathos, but like the hairpiece there’s very little underneath the irritating Phil Spector.

Speaking of irritating: Matthew Goode. That slick, silky, soft-spoken smarmy thing was fresh in The Lookout (2007), and fine for Watchmen (2009). By now, though, it’s tapped out, spent, yet here he is in Stoker, working it again.With flop indicator Nicole Kidman in the cast the U.S. debut of the esteemed Park Chan-wook (whose Oldboy Spike Lee is remaking) didn’t stand much of a chance at the boxoffice; with Goode semaphoring menace at every turn, it was sunk. Mia Wasikowska cuts an arresting figure as a huntress type, kept in check by mother Kidman, who unravels a family mystery; style, however, trumps logic at every turn, in a screenplay by said-to-be-former actor Wentworth Miller (Kidman’s co-star in The Human Stain). With the big reveal hinging on a child’s ability to move a massive quantity of sand in what appears to be minutes, I say, don’t give up your day job. Given forgettable roles are veterans Jacki Weaver and Phyllis Somerville as the Freudian/Hitchcockian/De Palmian stew never reaches full boil.

In wider release are two noteworthy films. The Place Beyond the Pines reunites writer-director Derek Cianfrance with Ryan Gosling, the star of his searing romantic melodrama Blue Valentine (2010). That film was a hard one to describe emotionally; it was difficult to describe the impact of its “tonal shifts,” to reuse the critical writing clichÁ© of last year. With this one the plot’s the pressure point, as it holds a few surprises best left unspoken. Suffice it to say that it’s a lengthy father-and-sons saga, unfolding from the 80s (Springsteen on the soundtrack, chain-smoking) to the present (Bon Iver, drug-taking), that reminded me more of Vincente Minnelli’s Home from the Hill (1960) than anything contemporary, with the feel and pace of a novel. An engrossing one, as Gosling’s motorcycle bandit, trying to provide for the child he wasn’t aware we had, crosses paths with corruptible lawman Bradley Cooper, who can’t escape a reckoning with his past. Cooper, an actor I’ve had problems with, is terrific here, and the strong cast includes Ray Liotta, Harris Yulin, and Mahershala Ali as a commendable father figure. (The leafy, working-class neighborhoods of upstate New York, where Cianfrance grew up, are themselves important characters, as they were in Blue Valentine.) Yes, it has unwieldy, clunky parts, and the final section isn’t quite as sure or well-developed as the third. But the ambition alone is worthy of praise.

In wider release are two noteworthy films. The Place Beyond the Pines reunites writer-director Derek Cianfrance with Ryan Gosling, the star of his searing romantic melodrama Blue Valentine (2010). That film was a hard one to describe emotionally; it was difficult to describe the impact of its “tonal shifts,” to reuse the critical writing clichÁ© of last year. With this one the plot’s the pressure point, as it holds a few surprises best left unspoken. Suffice it to say that it’s a lengthy father-and-sons saga, unfolding from the 80s (Springsteen on the soundtrack, chain-smoking) to the present (Bon Iver, drug-taking), that reminded me more of Vincente Minnelli’s Home from the Hill (1960) than anything contemporary, with the feel and pace of a novel. An engrossing one, as Gosling’s motorcycle bandit, trying to provide for the child he wasn’t aware we had, crosses paths with corruptible lawman Bradley Cooper, who can’t escape a reckoning with his past. Cooper, an actor I’ve had problems with, is terrific here, and the strong cast includes Ray Liotta, Harris Yulin, and Mahershala Ali as a commendable father figure. (The leafy, working-class neighborhoods of upstate New York, where Cianfrance grew up, are themselves important characters, as they were in Blue Valentine.) Yes, it has unwieldy, clunky parts, and the final section isn’t quite as sure or well-developed as the third. But the ambition alone is worthy of praise.

Rodney Ascher’s strangely absorbing documentary Room 237 takes us into the worlds of a handful of otherwise functional adults obsessed with Stanley Kubrick’s film of The Shining (1980). No, it’s not the faulty, if intermittently arresting, Stephen King adaptation that disappointed me as a teenager–it’s a tract about Native American genocide, a treatise on the Holocaust, a coded signal that Kubrick sent up to tell us that with 2001 he and the government colluded to fake the moon landing. It’s a secret history of many things if only you know how to put it together, and don’t listen to the men behind the curtain who will tell you otherwise. (Like any conspiracy theory, the scenarios floated here all sound reasonable after 100 minutes of lecturing.) My favorite explanation for all this is Ascher’s, in an excellent interview with Cineaste magazine (check out all the links): “Since there’s nothing much plot-based happening, you have time to meditate on the carpet patterns, the music selections, or the pictures on the wall.” (Or ponder the continuity errors that even a “perfectionist” director can make.) Whatever you make of all this theorizing, and it can be as amusing, startling, or wearying as a feature-length comments section attached to a Shining blog, there is fun to be had with Ascher’s approach, which replicates the movie right down to its period logo, and armchair Kubrickians will enjoy the juxtapositions and links made among his films. Outside the headspace of the participants it’s compelling to mull how home video culture has changed our viewing experience by giving us the tools for deep-dish analysis and creative manipulation of images formerly restricted to the cinema.

Rodney Ascher’s strangely absorbing documentary Room 237 takes us into the worlds of a handful of otherwise functional adults obsessed with Stanley Kubrick’s film of The Shining (1980). No, it’s not the faulty, if intermittently arresting, Stephen King adaptation that disappointed me as a teenager–it’s a tract about Native American genocide, a treatise on the Holocaust, a coded signal that Kubrick sent up to tell us that with 2001 he and the government colluded to fake the moon landing. It’s a secret history of many things if only you know how to put it together, and don’t listen to the men behind the curtain who will tell you otherwise. (Like any conspiracy theory, the scenarios floated here all sound reasonable after 100 minutes of lecturing.) My favorite explanation for all this is Ascher’s, in an excellent interview with Cineaste magazine (check out all the links): “Since there’s nothing much plot-based happening, you have time to meditate on the carpet patterns, the music selections, or the pictures on the wall.” (Or ponder the continuity errors that even a “perfectionist” director can make.) Whatever you make of all this theorizing, and it can be as amusing, startling, or wearying as a feature-length comments section attached to a Shining blog, there is fun to be had with Ascher’s approach, which replicates the movie right down to its period logo, and armchair Kubrickians will enjoy the juxtapositions and links made among his films. Outside the headspace of the participants it’s compelling to mull how home video culture has changed our viewing experience by giving us the tools for deep-dish analysis and creative manipulation of images formerly restricted to the cinema.

Speaking of headspace: Upstream Color. After a recent screening ended I typed the following notes on my iPhone: “Walden. Pigs. Grubs. Kidnap.” From there I think I figured out what jack of all trades Shane Carruth (of the intriguing time travel story Primer) was up to, only to read in various interviews that he prefers viewers to think in a non-linear way, to float with the movie on its widescreen, dreamily colored, sort-of sci-fi wavelength. So, go with it–you won’t get much from the actors, whose performances seem to have been invoked or summoned, or the opaque, fragmented storytelling, which nevertheless seemed to coalesce into something as the movie ended, or, perhaps, slipped away. It’s not, however, infuriating; I left the theater tranquil, if perplexed, and only wished that Carruth’s non-stop scoring hadn’t interfered with my impression of his awesomely singular vision. There’s nothing quite like it in release, so if it spreads to your town and you feel up to a challenge, attend.

[youtube id=”EDrPsekEwPs” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Comments