For almost 80 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose joins the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network to explore the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, we ponder the musical question: Is it possible to pogo in ice skates?

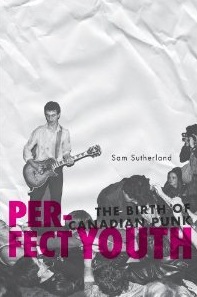

London, 1977. New York, 1975. Los Angeles, 1979. Punk rock arose (and arises still) in conditions of urban alienation. The Canadian scene, as chronicled in rock journalist Sam Sutherland’s new book Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk, was no exception.

London, 1977. New York, 1975. Los Angeles, 1979. Punk rock arose (and arises still) in conditions of urban alienation. The Canadian scene, as chronicled in rock journalist Sam Sutherland’s new book Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk, was no exception.

Canada is, contrary to perceptions abroad, a more urbanized country than the US, with its four largest cities accounting for a full 30% of the total population — that is, double the concentration as in the States. But — and here’s where the alienation comes in — those urban areas are geographically isolated from each other. The endless miles of prairie in between population centers made cheap, speedy touring nigh-impossible. Fans and bands alike were stuck with the venues available in their area. So it’s a misnomer to speak of ”Canadian punk” as a monolithic entity. As Sutherland tells the tale in this sprawling mosaic account, pieced together from interviews with dozens of musicians and fans, the varying scenes were highly localized, small-scale, and generally short-lived.

It’s a miracle that Canadian punk happened at all. The many arms of the Canadian establishment, so invested in the nation’s self-image as a bastion of decency and virtue, was hugely resistant. The very first gig by Toronto’s Viletones prompted the screaming newspaper headline ”Not Them! Not Here!” The twin obstructions of the musician’s union and the Mob — which owned many of the nightclubs — worked to keep punk bands out of most venues. But happen it did, in cities large and small across the sprawling nation. From Vancouver in the west to subarctic Winnipeg, from industrial Saskatoon to tiny St. John’s in Newfoundland, every city had at least one place for punks to play, and each had its own core audience who would come to every show.

This proved to be a mixed blessing; no band could play out too often, lest they wear out their welcome. Many performers scored additional stage time by recombining into the kind of one-off combos known vernacularly as ”fuck bands” — swapping instruments, banging out covers, or simply jamming onstage — and snagging opening slots. But few of these groups ever became seasoned road warriors the way the New York punks did; along with everything else, the mathematics were against them.

But the flame that burns briefest burns also brightest. The bands inspired both intense devotion and intense loathing, and managed to blaze all kinds of trails…

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments