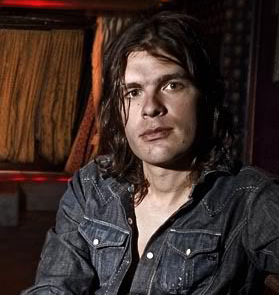

Paul Pope is a comics rock star. From his first self-published graphic novels in the early 1990s, his singular vision and staggering technique have led industry insiders to hail him as the future of comics — and as his self-bestowed nickname PulpHope indicates, he has embraced the role. I met him nearly twenty years ago, at a small-press expo in Montreal. The first and only issue of Buzz Buzz had just dropped, so this would have been 1996; Pope had only been publishing for two or three years at this point. But when he walked into the hotel bar, every head turned, as if Jim fucking Morrison himself had just strolled up. He’s just that kind of cat — handsome, gregarious, and charismatic.

Paul Pope is a comics rock star. From his first self-published graphic novels in the early 1990s, his singular vision and staggering technique have led industry insiders to hail him as the future of comics — and as his self-bestowed nickname PulpHope indicates, he has embraced the role. I met him nearly twenty years ago, at a small-press expo in Montreal. The first and only issue of Buzz Buzz had just dropped, so this would have been 1996; Pope had only been publishing for two or three years at this point. But when he walked into the hotel bar, every head turned, as if Jim fucking Morrison himself had just strolled up. He’s just that kind of cat — handsome, gregarious, and charismatic.

The thing is, Pope has got the chops to back up his rock-star swagger. His work blends formal discipline with bravura improvisation, Asian cool with European grime. His loose, kinetic brush, with its swirls of motion and puddles of black, shows the influence of masters like Hugo Pratt and Alex Toth — but his storytelling is allusive, elliptical, with moments of contemplative stillness even in his action sequences. He’s thinking of the page as a rhythmic unit, and his jagged beats are like no one else’s.

Pope’s work has encompassed original hardbacks, traditional pamphlets, and oversized magazine formats. He was one of the first western creators to develop work directly for the Japanese manga market, in his 1995 stint with the publishing giant Kodansha. He’s been relentlessly prolific, and his style is ever-evolving, but common threads running through his work include a fondness for science fiction elements, romantic fatalism, mouthy teenage girls, and weird libertarian digressions. After an extended detour reinventing Marvel and DC superheroes, he’s creating his own ”fighting comics,” aimed at younger readers, with the Battling Boy series of graphic novels.

Pope’s work has encompassed original hardbacks, traditional pamphlets, and oversized magazine formats. He was one of the first western creators to develop work directly for the Japanese manga market, in his 1995 stint with the publishing giant Kodansha. He’s been relentlessly prolific, and his style is ever-evolving, but common threads running through his work include a fondness for science fiction elements, romantic fatalism, mouthy teenage girls, and weird libertarian digressions. After an extended detour reinventing Marvel and DC superheroes, he’s creating his own ”fighting comics,” aimed at younger readers, with the Battling Boy series of graphic novels.

Heavy Liquid, from 2000, is a good place to start with his catalog. One of two original Pope works that DC put out through its Vertigo imprint (with DC also getting a third book, Pope’s politically-problematic take on Batman, out of the deal), Heavy Liquid is a lush cyberpunk noir set in a dilapidated future Manhattan and featuring one of Pope’s most striking narrative conceits.

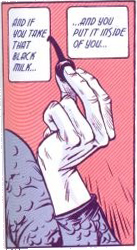

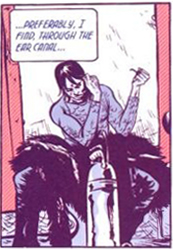

The ”Heavy Liquid” of the title is a bizarre contraband substance, extraterrestrial in origin, retrieved from a meteor strike site. Because of its rarity, the stuff is fabulously expensive — though no one seems quite sure what it does. Our protagonist, known only as S, is an ex-cop and full-time junkie eking out a living as an unlicensed private investigator. S has accidentally discovered that Heavy Liquid — which is semi-metallic and corrosive at room temperature — can be refined at high heat into a milky black substance with psychotropic properties. When he inserts a few drops into his ear, his sense of time and perception expands, and he feels sharper, more attuned with his surroundings. S has become addicted to the rush that the ”black milk” provides; as the story opens, he finds himself targeted for death, having stolen a quantity of Heavy Liquid from some criminal types.

Holing up in Chinatown, S takes on a job for a reclusive and fabulously wealthy art collector. The collector has invented a process to stabilize Heavy Liquid by casting it in alloy with bronze, and wishes to commission a sculpture in this new medium. He hires S to track down the talented young sculptress Rodan Esperella, who vanished into seclusion some years previously, and convince her to create the piece. S has reasons of his own for wanting to find Rodan; she and he were lovers, years ago, and it was their breakup — spurred by his growing addiction to the black milk — that prompted her disappearance in the first place.

Holing up in Chinatown, S takes on a job for a reclusive and fabulously wealthy art collector. The collector has invented a process to stabilize Heavy Liquid by casting it in alloy with bronze, and wishes to commission a sculpture in this new medium. He hires S to track down the talented young sculptress Rodan Esperella, who vanished into seclusion some years previously, and convince her to create the piece. S has reasons of his own for wanting to find Rodan; she and he were lovers, years ago, and it was their breakup — spurred by his growing addiction to the black milk — that prompted her disappearance in the first place.

A romp ensues through a variety of New York underworlds, both criminal and Bohemian. In the course of his investigation, S dodges a trio of clown-masked assassins, gets caught up in a teenage-girl gang initiation gone wrong, gets fucked up on black milk, and is hog-tied by a platoon of tiny robots controlled by a demented six year-old who believes she’s living on a pirate ship. He also finds himself pursued, for reasons unknown, by a sinister government agent.

Finally, having traced Rodan to Paris, S secures the collector’s commission; the lovers, now irreparably estranged, say their final goodbyes, and S boards a train to Rome — only to find the G-Man waiting for him. The Heavy Liquid that S stole, as it turns out, has explosive properties, and there are a number of parties eager to use it as a weapon. In the course of his escape, S makes his own discovery about the black milk — that what he thought was a mere drug just might have a will and intelligence of its own…

It’s a breathless adventure, raucous and often funny, shot through with Pope’s trademark lyricism and tenderness. The art, rendered in a unique two-color process, is frankly gorgeous in the moody, shadowed style of classic noir. And the Heavy Liquid itself makes for an inspired, multi-layered metaphor. At first it seems a simple Maguffin, an object of desire to set the plot in motion, but as the narrative moves forward it becomes a complex symbol. On a basic, near-literal level, Heavy Liquid is ink; but as a stand-in for the artistic process as a whole, it encompasses the endless possibilities of medium, the intoxicating rush of art, the outlaw danger, the appropriation of aesthetics in service of ideology or even violence — and, in the end, it becomes a vehicle for contact with the numinous, with something strange and true and hitherto-unimagined.

Like all of Pope’s work, Heavy Liquid is steeped in music. The title comes from a Stooges tune, and S is indeed referred to repeatedly as ”the stooge.” References abound to rock n’ rollers from Mick Jagger to Nick Cave. What follows is an attempt not to trace Pope’s allusions (although there’s a little of that), but to evoke the themes and atmosphere of his work — the squalling decay of New York’s neighborhoods, with their street festivals and their hazardous nightlife, where you feel like you should pack your passport just to walk uptown; every block like its own small town, with its own customs and local characters; a dream-city of screeching metal and sidewalk steam, with strange music and half-heard conversations drifting from every window as you pass by, bound for some treacherous rendezvous of your own.

Heavy Liquid (1:21:51)

PLAYLIST

Conceptual Theater intro bumper

Loisaida [excerpt] — Joe Jackson

Yo Pumpkin Head [edit] — Yoko Kanno & the Seatbelts

Black Milk — Massive Attack with Elisabeth Fraser

Eardrum Buzz — Wire

Chinatown My Chinatown — Firehouse Five Plus Two

Modern Art — Art Brut

No Surprises — Radiohead

Private Goes Public — Suzanne Vega

Pablo Picasso — John Cale

The Clown Song — Thin White Rope

Junk — The Pogues

Haul On The Bowline — Bob Neuwirth

Green Jeans — The Fabulous Flea-Rekkers

He’s On Drugs Again — Some Girls

Chain — Chris Whitley

Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On) — Talking Heads

Trouble — The Rakes

(montage: I Don’t Like the Drugs (But the Drugs Like Me) — Marilyn Manson)

Cameras In Paris — The Fixx

Brand New Life — Young Marble Giants

Trans-Europe Express [fade] — Kraftwerk

Shadowman [edit] — Afro Celt Sound System

Contact — Daft Punk

Conceptual Theater outro bumper

atmospheres and institials contains elements of recordings by the U.S. Steel Cello Ensemble and the BBC sound effects library

Zack will be in this space in two weeks’ time; I’ll be back in December with something that should… should… dammit, I had something for this. Anyway, until then, look sharp — and be careful about what you put in your ears.

Comments