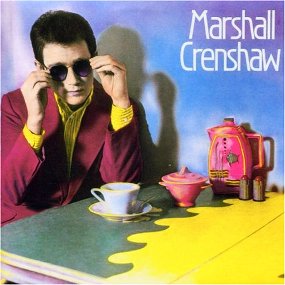

He showed up in our record stores with an art-deco album cover and the visage of a New Wave Buddy Holly. He arrived with a freshly inked major-label deal and on a tidal wave of media hype, armed with a clutch of catchy songs that seemed to re-stir the protoplasm of rock and roll. Having conquered New York with an indie single and a tight combo that tore up the clubs, he was declared ready to push aside the ’70s holdovers who were dominating early-’80s rock, and become the proverbial Next Big Thing … or at least, as Rolling Stone referred to him at the time, ”the next necessary thing.”

He showed up in our record stores with an art-deco album cover and the visage of a New Wave Buddy Holly. He arrived with a freshly inked major-label deal and on a tidal wave of media hype, armed with a clutch of catchy songs that seemed to re-stir the protoplasm of rock and roll. Having conquered New York with an indie single and a tight combo that tore up the clubs, he was declared ready to push aside the ’70s holdovers who were dominating early-’80s rock, and become the proverbial Next Big Thing … or at least, as Rolling Stone referred to him at the time, ”the next necessary thing.”

The extent to which NBT status didn’t happen for Marshall Crenshaw remains a disappointment, and something of a mystery, to this day. But that certainly doesn’t mean the ”necessary” label wasn’t operative then, or isn’t now. For his legions of (aging) fanboys and fangirls, Marshall Crenshaw remains a quintessential power-pop blast, not to mention a debut album that launched one of the sturdiest rock careers of the last three decades.

If any of that seems an overstatement, you’ll have to forgive me — I’ve been in the tank for Marshall Crenshaw since the week it came out. I was 16 at the time, and a sucker for the kind of critical consensus that veritably screamed, ”Buy this record now!” … not to mention a sucker for the kind of sound the album’s first single, ”Someday, Someway,” made when it came out of a radio. For me, the album was a primer on how to grow out of the hopeless-romantic idiocy that had kept me serially pining away for unattainable (and usually, in retrospect, uninteresting) high-school princesses. Crenshaw pointed the way toward a mature, still vaguely optimistic, late-adolescent skepticism — the kind that would send me out looking for a Cynical Girl instead of a cheerleader. Did it work? Not really, or at least not consistently — but at least now I had the roadmap, and the big-beat-driven impetus, to find me a Brand New Lover, ’cause there isn’t any other cure.

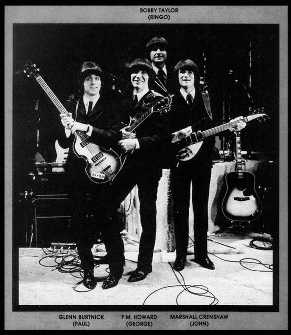

Crenshaw had cooked up his idiosyncratic stew of retro and cutting-edge sounds during an upbringing that was rather unusual among second-generation rockers. Raised in the Detroit of both Motown and the MC5, he turned off the radio in his late teens and instead steeped himself in the rock and R&B 45s of his early childhood. Frustrated by the lack of opportunity for a musician in his hometown during the mid-to-late ’70s, he answered a casting call for Beatlemania and headed for New York as a John Lennon understudy. He spent a year and a half with the musical, on Broadway and later on tour, then returned to NYC with a new focus and energy — his immersion in Fab Fourdom having served a role similar to the Beatles’ own apprenticeship in Hamburg. It wasn’t long before Crenshaw carved out a prominent place for himself in a city that was up to its ears in New Wave clubs.

Crenshaw had cooked up his idiosyncratic stew of retro and cutting-edge sounds during an upbringing that was rather unusual among second-generation rockers. Raised in the Detroit of both Motown and the MC5, he turned off the radio in his late teens and instead steeped himself in the rock and R&B 45s of his early childhood. Frustrated by the lack of opportunity for a musician in his hometown during the mid-to-late ’70s, he answered a casting call for Beatlemania and headed for New York as a John Lennon understudy. He spent a year and a half with the musical, on Broadway and later on tour, then returned to NYC with a new focus and energy — his immersion in Fab Fourdom having served a role similar to the Beatles’ own apprenticeship in Hamburg. It wasn’t long before Crenshaw carved out a prominent place for himself in a city that was up to its ears in New Wave clubs.

Soon he was making demos, then records — hooking up with producer/magazine publisher/Shake Records owner Alan Betrock for the one-off single ”Something’s Gonna Happen.” It was right about the time that Robert Gordon scored a local NYC hit with Crenshaw’s composition ”Someday, Someway” that the majors came calling. He went into the studio intending to produce his debut album himself, but when he discovered he was in over his head he called in the Record Plant’s house producer, Richard Gottehrer, to run the boards.

The results conveyed Crenshaw’s own somewhat jaded romanticism (”Girls,” ”Not for Me”), celebrated his New York environs (”Rockin’ Around in NYC,” ”She Can’t Dance”), and paid tribute to his influences (Arthur Alexander’s ”Soldier of Love”). Beginning with ”There She Goes Again” and concluding with ”Brand New Lover,” the album seemed (but only seemed — Crenshaw says any hints of a ”concept” were unintentional) to cover the full spectrum of pre-marital romantic experience. And it did so with a sound that was rooted in his beloved rockabilly and girl-group singles.

I spoke with Crenshaw at length about his entire career, including those early days, for a Popdose Interview a couple years ago. Earlier this year we spoke again, specifically about the debut album and the swirl of activity that surrounded its making, promotion and reception. Crenshaw clearly had been thinking about the subject for a while, having participated in a 30th-anniversary celebration of his recording debut a year ago this week at New York’s City Winery. When we spoke he was taking a break from his version of the never-ending tour (which hits California this week, by the way); limbering up his DJing voice for his weekly, typically eclectic radio gig on New York’s WFUV-FM; and continuing to plot an online subscription scheme for a series of new vinyl EPs. Despite all that, he proved willing to indulge another of my trips down memory lane.

[youtube id=”YKZkhdvSNSI” width=”600″ height=”350″]There are a lot of clichÁ©s about the artist who goes into the studio on a high to record a debut album, having just gotten signed and all that. Did you do a lot of writing for the album in the weeks before you went into the studio?

Actually, by the time I went in to do the record, I hadn’t written a new song in months. I had stockpiled a whole bunch of songs in ’79 and ’80, and I finally stopped because I felt I was repeating myself. The last one I wrote during that time was ”For Her Love,” which at the time I thought was intensely mediocre, so I thought I should just stop before it got any worse. When we chose the songs we were going to include on the album, the only things that got left off were ”For Her Love” and ”Whenever You’re On My Mind.”

You must have been rather intimate with those songs from playing them live.

Yeah. We had been playing them live for several months. And I had recorded a lot of them a few times already before I got signed. I recorded a bunch of demos with my brother — those were great recordings [most of which are now available on Crenshaw’s 9-Volt Years collection or the expanded edition of Marshall Crenshaw]. The second time I recorded was in a studio, with a bunch of guys I don’t want to talk about. And we did ”Something’s Gonna Happen” for Shake Records. And then Warner Bros. sent us into a studio.

Did all that preparation make the recording process go more smoothly?

Did all that preparation make the recording process go more smoothly?

It was probably not a good thing, actually. The songs got more watered down each time I redid them. I was really happy the first time I recorded them, and thought they were just fine as they were. I remember that when we made the rounds of the Warners offices in Burbank, when I was trying to decide whether to sign with them or RCA, I had a meeting with a producer whose name you’d recognize. We listened to ”Something’s Gonna Happen,” and he asked me who had produced it. At that point I committed a grievous sin, and said I had produced it myself. Really it was Alan Betrock, but I opened my big mouth and cut him out of the picture. I’ll regret that til the day I die.

That conversation started the ball rolling toward me producing the first record. I really wanted someone to let me do it, which is why I said what I did. So I went into the studio, and I started floundering right away. The fact that I had recorded those songs already made it difficult to get inspired. That first time, which I had thought was really successful, I had used my own gear. But when we got into the Record Plant I was just overwhelmed by the experience.

I had been in two studios in NYC making Robert Gordon records — the Record Plant, where we worked with Richard Gottehrer, and the Power Station, where Scott Litt was the engineer. I’ve thought at times over the years, what would have happened if I’d gone into the Power Station with Scott for my record, instead of choosing door number two?

Anyway, it was a big old psychodrama making the record — there were a lot of bumps in the road. Eventually Richard came in, and that took some of the pressure off. What finally came out was sort of a compromise … a decent compromise.

I wasn’t happy. I remember the first time we played it back for the label, I thought, ”Oops!” We re-sequenced it, cut a couple songs, and I suppose that made it a bit better. I just remember that whole experience as being really hard. After that, when we got ready to do the second album, I said, ”There’s no way I’m going to go through that again.” And fortunately Steve Lillywhite was able to get a sound on Field Day that was closer to what I had wanted for the first record.

[youtube id=”ApmeElOc15k” width=”600″ height=”350″]Why did you choose not to include a version of ”Something’s Gonna Happen” on the album?

I don’t know — I honestly don’t remember. I’m glad we didn’t re-record it, though. I like ”Something’s Gonna Happen,” sonically speaking, more than a lot of tracks on the debut album. That song rocks! To be honest, I didn’t even want to record ”Someday, Someway.” My thought at the time was that Robert had had a big hit in New York with it — he just missed having a top 40 hit — so I thought people had heard it enough already. But I was kinda ordered to do it by the Warners people. Obviously, I’m glad I did.

Were there other ”compromises,” as you called them, involved in getting the album accepted by Warners?

The compromises were probably more with myself than with Warners, you know? We finally got the record to the point where everybody was cool with it, and was willing to go forward. It took a lot of doing to get the record done. The promotion was another thing altogether.

You and I talked last time about how you responded to the grind of promoting and touring. But at that point it was all new to you.

I was kinda terrified at that time, in general. It was a hell of a learning experience to get out there and actually be in show business. It wasn’t great. Well, that’s not completely true — we really did have a lot of fun — but the show-business part was not the fun part.

I remember this one moment when I was on the phone with the wife of a radio station programming director, and I was told that if I would sing ”Happy Birthday” to her, they’d add my record. I remember thinking, I got into rock and roll so I wouldn’t have to kiss people’s asses, and yet here I am…

You know, you couldn’t be ambivalent about that promotional stuff if you wanted to succeed. It’s probably just as true now, but it was definitely true when I was starting out. And I remember being around people who were really driven about this stuff — people who were willing to do whatever was asked of them. I didn’t have that mindset.

We also discussed last time how it wasn’t until years later that you began to get the full story of the stuff that got in the way of your debut being marketed the way it could have been.

We also discussed last time how it wasn’t until years later that you began to get the full story of the stuff that got in the way of your debut being marketed the way it could have been.

When my A&R person at Warners passed away a few years ago — Karen Berg, she was really a beloved person to me, I really dug her — at Karen’s funeral somebody finally told me that nobody at the label was ever willing to give any money to promote that record. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard something like that, but it was interesting to hear it at that moment. I had been in the studio doing my Downtown album when this guy sought me out — he literally called me on the phone in the studio. I had met this guy when the first album was out, he was a big promotion guy at Warners. And so he got me on the phone and he apologized to me. He said, ”I still have regrets about not banging singles out on the first album, one after another.” He said there was a lot of tension between the East Coast and the West Coast people at the label back then.

I didn’t know any of that was going on, but I was an East Coast signing, so there was problematic stuff going on with the marketing people in Burbank. When that book Hit Men came out, my dad read it and he said to me, ”According to this book, when your first album came out Warners on the West Coast was boycotting the use of East Coast indie [promotion] firms.” He went through the whole story that was in that book, and a lot of things became clearer to me.

Are there songs from the debut album that you still really enjoy playing live, and others that you avoid?

”There She Goes Again” I still really dig playing. I cut the time in half, like I’m doing with a bunch of songs — not to slow it down, but to reinterpret it from a groove standpoint. I don’t have any problems playing ”Someday, Someway” … ”Mary Anne” … there are probably seven or eight I still love playing. The ones I don’t play that often are ”Brand New Lover” and ”She Can’t Dance.” Those were kind of slapped together in the first place, and they don’t really resonate for me now. I actually refused to sing ”She Can’t Dance” during those 30th-anniversary shows at City Winery. There were probably a few people who were disappointed, but nobody started a riot or anything.

[youtube id=”lkWxF85LqRE” width=”600″ height=”350″]Having lived with it for three decades, how do you look back on the album itself at this point in your career? Does all the business stuff get in the way of your appreciation for it?

I guess I’d rate it pretty highly, compared to everything else I’ve done. I don’t say this to brag, because I’ve made a lot of mistakes, but I was a good artist from the start. I had a sense of purpose about every little stroke, a certain amount of self-knowledge about how I wanted to express myself, even at that point.

You know, the business stuff was not easy, the promotional stuff was not easy. And when the album didn’t really do what some people had thought it was going to do, we just had to go forward from that. Again, the show-business part of the whole thing really scrambled my brain, and it stayed scrambled for a while.

There was a lot of throwaway stuff on those major-label albums, but the lyric writing on that first album is really good and strong. Down the road, it got harder for me to do that, in the middle of everything else you have to do to keep going as a major-label artist. When it came time to work on the Best-Of [the Rhino collection This Is Easy, from 2000], when it came to winnowing down what we were going to include, I went through all those songs from the first album and thought, Yeah, I’ll stand by that stuff. I was really trying hard to do my best work at that time, and I was aware of everything that I was looking to accomplish.

It’s hard to talk about what I was thinking and doing 30 years ago, even though I have a clear memory of it. As we were getting ready for the City Winery gig, I was thinking it’s just funny that anybody wants to talk about it, or remember it to this extent. But thanks for the interest, man. Thanks for asking.

For an even longer interview with Crenshaw about his debut, including track-by-track analysis, check out this page.

Comments