A rumble of seismic proportions shook the Billboard 200 album chart in the magazine’s issue dated May 25, 1991. That’s the week when Billboard, for the first time, based the chart entirely on SoundScan point-of-sale data, jettisoning the old-fashioned method of allowing many stores to self-report their sales. The results were surprising, in terms of the computerized data’s effect on individual albums’ chart placements. They were instructional, too, revealing that sales in a few genres had been systematically under-reported by the old methodology — namely, those reaching primarily grown-up audiences. Adult contemporary and light-R&B artists suddenly found themselves reaching new chart heights — but the true revelation was the suddenly recognizable, and massive, popularity of country music.

A rumble of seismic proportions shook the Billboard 200 album chart in the magazine’s issue dated May 25, 1991. That’s the week when Billboard, for the first time, based the chart entirely on SoundScan point-of-sale data, jettisoning the old-fashioned method of allowing many stores to self-report their sales. The results were surprising, in terms of the computerized data’s effect on individual albums’ chart placements. They were instructional, too, revealing that sales in a few genres had been systematically under-reported by the old methodology — namely, those reaching primarily grown-up audiences. Adult contemporary and light-R&B artists suddenly found themselves reaching new chart heights — but the true revelation was the suddenly recognizable, and massive, popularity of country music.

Amongst the country CDs that began flooding the chart that week, one result really stood out. Garth Brooks’ 13-month-old album No Fences, which had been languishing for months in the lower reaches of the top 40 and had placed at number 16 in the May 18 issue, suddenly was number 4 — and it remained in the top 10 through the summer that followed. The album had peaked at number 3 shortly after its release, but it seems clear now that, had universal computer tracking been in place from the beginning of its run, it might have spent several weeks (if not months) atop the pop albums chart, as it had on the country chart (23 weeks). All told, No Fences has been certified by the RIAA for sales of more than 17 million copies — including more than 9 million registered by SoundScan, making it the second-most successful country album of the last two decades.

If you’re wondering why this column has commenced with such a detailed rehashing of chart histories and sales figures, there’s a good reason: The country-music industry of the early ’90s, not to mention Brooks himself, was obsessed with these numbers and their broader meaning. Indeed, tracking the commerce racked up by No Fences, and Brooks’ oeuvre in general, has vastly overshadowed discussions of the quality of his work in most analyses of his recording career. Those stunning numbers sparked a decade of expansion in Nashville, and a new understanding of country’s relevance to the aging audience that had been raised on ’60s and ’70s rock and pop. If you’re wondering why all your favorite songwriters now live in the 615 area code, blame No Fences.

All of this was top-of-mind as Brooks and Capitol Nashville prepared for the September 1991 release of his follow-up album, Ropin’ the Wind. By that point Music City recognized what it had in Brooks: a rock- and singer/songwriter-inspired savior who could lead the entire country genre to new heights among suburbanites, many of whom were turning away from pop radio as that format became more R&B-dominated. His self-titled 1989 debut had updated and transcended the ”New Traditionalist” movement that had dominated Nashville during the late ’80s (Randy Travis, George Strait, Dwight Yoakam, Steve Earle, etc.), and No Fences had not merely allowed Brooks and his label to start printing money — it had gone a long way toward making country, for a time, the most listened-to format on the radio nationwide, and had opened doors (both on radio and TV) for a generation of young artists like Clint Black, Alan Jackson and Travis Tritt.

All of this was top-of-mind as Brooks and Capitol Nashville prepared for the September 1991 release of his follow-up album, Ropin’ the Wind. By that point Music City recognized what it had in Brooks: a rock- and singer/songwriter-inspired savior who could lead the entire country genre to new heights among suburbanites, many of whom were turning away from pop radio as that format became more R&B-dominated. His self-titled 1989 debut had updated and transcended the ”New Traditionalist” movement that had dominated Nashville during the late ’80s (Randy Travis, George Strait, Dwight Yoakam, Steve Earle, etc.), and No Fences had not merely allowed Brooks and his label to start printing money — it had gone a long way toward making country, for a time, the most listened-to format on the radio nationwide, and had opened doors (both on radio and TV) for a generation of young artists like Clint Black, Alan Jackson and Travis Tritt.

The music industry commonly uses the word ”consolidation” to describe a label’s efforts to capitalize on, and broaden, the success of an act’s last release with its next one — and if there’s one word that describes the intent and the achievement of Ropin’ the Wind, it’s consolidation. The album — here comes some more chart ephemera — became the first ever to debut simultaneously atop the Billboard 200 and the country albums chart. It spent 18 weeks at number one during four separate runs atop the pop list. It has been certified platinum (1 million sales) 17 times over. And just for the sake of perspective: While Nirvana justifiably made history of its own, and placed a marker for alternative music’s rising popularity, when Nevermind scaled the Billboard 200 in January of ’92, it was there for just two non-consecutive weeks — and both times it was dislodged by Ropin’ the Wind, which racked up 10 more weeks at number one during the peak of Nevermind’s popularity.

But was it any good? More important, considering those sales … does it matter?

To the extent that it does, Ropin’ the Wind is a solid, if unremarkable, ”hat act” country album. Like most of Brooks’ long-players, it features a mix of melodramatic country-rockers, hokey honky-tonk anthems, faux-gritty paeans to the ”western” life, and sincere balladry — but it includes little of his best work in any of those styles. From start to finish, it seemed designed to … yes … consolidate the achievements of No Fences, and as a result it wound up sounding like a lesser version of its predecessor.

Start with the lead single, ”Rodeo,” written by frequent Brooks collaborator Larry Bastian (he had placed the ballad ”Unanswered Prayers” on No Fences). The lyric updates cowboy mythology to encompass the dudes who strap on chaps and ride bulls for show — but the rock-flavored arrangement and production are a hash on the biggest crossover hit from the last album, ”The Thunder Rolls.” That song had been about cheating and getting caught, and its video had become notorious (and earned VH1 airplay) with its allusions to domestic violence. ”Rodeo,” on the other hand, had no ambition more controversial than riding the coattails of ”Thunder” straight onto the radio dial — so it came as something of a shock when the single got bucked off the chart after peaking only at number 3. Perhaps country’s listenership was going cosmopolitan even faster than Nashville imagined.

Start with the lead single, ”Rodeo,” written by frequent Brooks collaborator Larry Bastian (he had placed the ballad ”Unanswered Prayers” on No Fences). The lyric updates cowboy mythology to encompass the dudes who strap on chaps and ride bulls for show — but the rock-flavored arrangement and production are a hash on the biggest crossover hit from the last album, ”The Thunder Rolls.” That song had been about cheating and getting caught, and its video had become notorious (and earned VH1 airplay) with its allusions to domestic violence. ”Rodeo,” on the other hand, had no ambition more controversial than riding the coattails of ”Thunder” straight onto the radio dial — so it came as something of a shock when the single got bucked off the chart after peaking only at number 3. Perhaps country’s listenership was going cosmopolitan even faster than Nashville imagined.

Brooks would fare better with the album’s second single, which laid bare his intention to expand his crossover audience. He had plucked the vaguely bluesy ballad ”Shameless” off Billy Joel’s 1989 album Storm Front, and had gained considerable buzz from what was seen as a rather blatant ”rock move” — though once the pedal-steel had been applied and Brooks had somehow amped up his Oklahoma twang even more than usual, his version was countrified enough to send it straight to the summit of Top Country Singles. Interestingly, however, Brooks still couldn’t sniff the Hot 100 — even with all those sales, all that hype, and a Billy Joel pedigree, pop radio in the early ’90s remained so closed to country that only an R&B-tinged cover could sneak a Nashville tune onto the charts. (See All-4-One’s massive hit versions of John Michael Montgomery’s ”I Swear” and ”I Can Love You Like That,” from 1994-95.)

Three more singles from Ropin’ the Wind would become big country hits. The heart-rending ballad ”What’s She Doing Now” (#1 for three weeks) was fine, but not quite in the same league as the earlier ”If Tomorrow Never Comes,” which it resembles; ”Papa Loved Mama” (another #3) is one of those honky-tonkers whose lyrical twists are wince-inducing to anyone whose senses aven’t been dulled by years of country radio (”Papa loved mama, mama loved men / Mama’s in the graveyard, papa’s in the pen”). Even within the narrow confines of that genre, it can’t hold a candle to his earlier ”Friends in Low Places” or his later ”American Honky-Tonk Bar Association.”

Three more singles from Ropin’ the Wind would become big country hits. The heart-rending ballad ”What’s She Doing Now” (#1 for three weeks) was fine, but not quite in the same league as the earlier ”If Tomorrow Never Comes,” which it resembles; ”Papa Loved Mama” (another #3) is one of those honky-tonkers whose lyrical twists are wince-inducing to anyone whose senses aven’t been dulled by years of country radio (”Papa loved mama, mama loved men / Mama’s in the graveyard, papa’s in the pen”). Even within the narrow confines of that genre, it can’t hold a candle to his earlier ”Friends in Low Places” or his later ”American Honky-Tonk Bar Association.”

Then there was the album-closing ”The River,” which is easily the best track on Ropin’ the Wind and which slotted nicely in the newfangled ’90s tradition of gospel-tinged, inspirational country anthems (the Judds’ ”Love Can Build a Bridge,” Martina McBride’s ”A Broken Wing,” etc.). ”The River” occupies a point on that spectrum that’s less bombastic than ”We Shall Be Free,” the song that would lead off Brooks’ next album and prove way too liberal for country radio. But it was somewhat more obvious in its dramatics than was ”The Dance,” the ballad that had lifted his career to a new level in 1990.

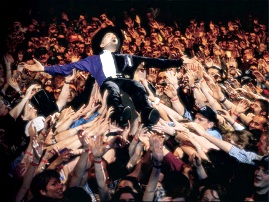

Following the commercial triumph of Ropin’ the Wind, Brooks went on to model atrocious western wear on the booklets for several more chart-topping CDs through the decade, though the returns inevitably diminished a bit through The Chase, In Pieces, Fresh Horses and Sevens. He also became the biggest live act on the planet, putting on shows whose energy and duration (if not necessarily quality) rivaled the Springsteen marathons of the ’70s and ’80s. He finally cracked the Hot 100 in 1994 … with a version of ”Hard Luck Woman,” from the Kiss My Ass tribute album. He had haphazard success with further crossover attempts: A cover of Aerosmith’s ”The Fever” couldn’t even crack the country Top 20, but his version of Bob Dylan’s ”To Make You Feel My Love” became an adult-contemporary hit after it was featured in the Sandra Bullock movie Hope Floats.

His biggest pop hit, the top-5 ”Lost in You,” came from his much-maligned 1999 ”Chris Gaines” project, for which he bewilderingly chose to don a wig and pose as a fictional rock star. Ziggy Stardust he wasn’t — but the attempt betrayed a wanderlust that (along with family troubles and a desire to be closer to his young daughter) eventually led him to give up making records and touring shortly after the millennium. Since then he has become tabloid fodder (divorcing his first wife and eventually marrying fellow singer Trisha Yearwood), has continued to blaze new (if not particularly street-cred-friendly) commercial trails through a huge exclusive deal with Wal-Mart, and most recently has become one of the more recent acts to make Las Vegas a stage home away from home. Just last month, he announced from that Vegas stage that his daughter would soon be turning 18, and that, once she does, he’ll be ready to hit the road again.

His biggest pop hit, the top-5 ”Lost in You,” came from his much-maligned 1999 ”Chris Gaines” project, for which he bewilderingly chose to don a wig and pose as a fictional rock star. Ziggy Stardust he wasn’t — but the attempt betrayed a wanderlust that (along with family troubles and a desire to be closer to his young daughter) eventually led him to give up making records and touring shortly after the millennium. Since then he has become tabloid fodder (divorcing his first wife and eventually marrying fellow singer Trisha Yearwood), has continued to blaze new (if not particularly street-cred-friendly) commercial trails through a huge exclusive deal with Wal-Mart, and most recently has become one of the more recent acts to make Las Vegas a stage home away from home. Just last month, he announced from that Vegas stage that his daughter would soon be turning 18, and that, once she does, he’ll be ready to hit the road again.

Comments