Every now and then, some erudite so-and-so will get on TV or on talk radio and opine about the sordid state of the arts. He (sometimes she, but mostly he) will complain that we haven’t got the Great American Novel yet, and at this pathetic rate — with these pathetic smartphone zombies at the helm — we never will. It is a statement of supreme ignorance.

Every now and then, some erudite so-and-so will get on TV or on talk radio and opine about the sordid state of the arts. He (sometimes she, but mostly he) will complain that we haven’t got the Great American Novel yet, and at this pathetic rate — with these pathetic smartphone zombies at the helm — we never will. It is a statement of supreme ignorance.

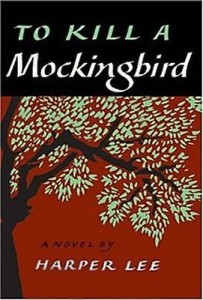

Everyone knows that To Kill A Mockingbird is the greatest Great American Novel. Even author Harper Lee knew it. That was why the book she wrote before it, the book an editor told her to take back and work over again (leading to the creation of Mockingbird), stayed “disappeared” for ages. It was in the care of her sister, also her literary agent, and might have stayed that way if Ms. Harper’s sister hadn’t passed first. I won’t belabor the point that I still believe Go Set A Watchman is the illegitimate successor to To Kill A Mockingbird, but this is all I’ll say on the matter. It’s all that is necessary.

Here’s why: In the legendary novel of a small Southern town, which had a tendency to have small problems, now facing some of the biggest problems of that day and today, everything you needed was there. You had a superhero as potent as Clark Kent. You had a fearful mystery man who was truly misunderstood, but he was considered a man in everyone’s eyes anyway. Then you had another man who wasn’t afforded that same benefit of the doubt. And you had the perspective of children, which had the perfect eyesight with which to view such complications. As children can see a situation and not be able to understand it, our heroine Scout illustrates a situation beyond understanding. Her innocence, our ignorance. It is a perfect analog.

Here’s why: In the legendary novel of a small Southern town, which had a tendency to have small problems, now facing some of the biggest problems of that day and today, everything you needed was there. You had a superhero as potent as Clark Kent. You had a fearful mystery man who was truly misunderstood, but he was considered a man in everyone’s eyes anyway. Then you had another man who wasn’t afforded that same benefit of the doubt. And you had the perspective of children, which had the perfect eyesight with which to view such complications. As children can see a situation and not be able to understand it, our heroine Scout illustrates a situation beyond understanding. Her innocence, our ignorance. It is a perfect analog.

I remember a passage from Stephen King’s workbook/love letter to his craft, On Writing. He pondered about the writers who pumped out multitudes in their lifetimes, all with a fairly steady level of quality. He understood that they shared his love of the creating, the process, the doing. In contrast, he thought about Harper Lee and how she walked away from it all after that one book. (Forget about how that one book would set her up comfortable for the rest of her life.) King wondered how she could not ever feel that itchy pang to write again. Maybe she did. Maybe To Kill A Mockingbird was so monolithic in her mind she was intimidated.

I don’t want to think that way. I’d rather think that, having made something so essential and perfect, she thought it best to leave that be. It is an innocent — okay, probably an ignorant — position to take.

There’s going to be a lot of conversation about why it had to be Atticus Finch that is the champion against racism. It’s already going on, really. The short answer is that the required evolution probably needs to begin in white America more than anywhere else. People loved Atticus because he represented that evolution not because he was white, but because he saw in Tom Robinson another human being who deserved fair due process, in a time where the black man was so hauntingly, sickeningly articulated by Billie Holiday as the strange fruit hanging from the sycamore trees. As the song spoke of how whites saw the “non-being” of blacks, this novel indicated the scales were falling from some men’s eyes, and they were going to share those lessons with their children. The allegation against Robinson might be false. It might be true. He still deserved fairness because he was a human being. This is why the depiction of Atticus in Watchman was so painful to so many. It showed the evolved human being as being no such thing. Indeed, if Atticus could fall, was there any hope for us? Our example was a clay-footed sham.

There’s going to be a lot of conversation about why it had to be Atticus Finch that is the champion against racism. It’s already going on, really. The short answer is that the required evolution probably needs to begin in white America more than anywhere else. People loved Atticus because he represented that evolution not because he was white, but because he saw in Tom Robinson another human being who deserved fair due process, in a time where the black man was so hauntingly, sickeningly articulated by Billie Holiday as the strange fruit hanging from the sycamore trees. As the song spoke of how whites saw the “non-being” of blacks, this novel indicated the scales were falling from some men’s eyes, and they were going to share those lessons with their children. The allegation against Robinson might be false. It might be true. He still deserved fairness because he was a human being. This is why the depiction of Atticus in Watchman was so painful to so many. It showed the evolved human being as being no such thing. Indeed, if Atticus could fall, was there any hope for us? Our example was a clay-footed sham.

That’s why To Kill A Mockingbird will continue to move people a century from now, long after our sequel/reboot culture has grown up to embrace the scary rewards of the unfamiliar over the recycled. That’s why Harper Lee will continued to be lionized. That’s why the search for the Great American Novel is a foolish one. She gave it to us. Now it is up to us to aspire to those heights, in creativity and humanity.

Comments