There’s a feeling you get. You know the one.

You’re listening. It’s a song you’ve heard before, maybe many times. Heard it, but really never listened. One of those songs that always just sort of been there. But this time, on your hundredth hearing, or your thousandth, something is different. Something jumps out at you: a lyric you’ve never caught, a familiar snatch of melody repurposed, some quote or allusion or reference that gives you a shock of recognition.

And this song, this evergreen, this classic-rock chestnut, this battered and clapped-out auld whorehorse becomes something wonderfully fresh and new. And a secret unfolds in your mind. No: Not unfolds. The opposite. Something opaque and featureless assumes new form and contour, a blank sheet of paper resolving into an origami swan.

That feeling. There must be a word for that.

It’s difficult, in practical terms, to define your Old Professor’s precise field of academic interest — turns out you can’t actually get a degree in Being A Smart-Ass, more’s the pity — but Modern Languages was not a part of the curriculum. I’ve retained nothing from two years of college-level Spanish but a ”hilarious” habit of pronouncing California place names in a bogus Castilian lisp (e.g., ”Loth Ankheleth”). To all purposes, I am — but for a smattering of high school French — solidly monolingual.

In a globalized entertainment-industrial complex, this makes me a minority market share. There’s literally a whole world of culture out there for which I am not the primary intended audience. And were I determined to stick with exclusively-Anglophone amusements — in the manner of one of those fundamentalist weirdoes who only consumes ”Christian”-branded entertainment — I would find the pickings too slim for my liking.

I take my pop thrills wheresoever I can find them; and the best — perhaps the only — way to guarantee a steady supply of fresh cultural product to punch my pleasure buttons is to cast my net as wide as my inherently limited options will allow. Luckily, I am not afraid of subtitles; nor am I hung up with a need to see ”people who look like me” on the screen. (I get plenty of that, thanks very much, just owning a mirror.)

But the numbers are against me. Only a tiny percentage of books written in languages other than English ever get translated; only a fraction of the movies and comics and TV shows produced around the world ever make it abroad, even with subtitles. For every Stieg Larsson or Haruki Murakami, for every Oldboy or Troll Hunter or Motorcycle Diaries, for every Persepolis, every Epileptic, every Yotsuba&! that breaks through to an Anglophone audience, there are dozens, perhaps hundreds of cultural products — no less deserving of wider exposure — of which English-speaking consumers will remain forever ignorant.

But music… ahhh, music! Radio doesn’t come with subtitles, but the glorious thing is that it doesn’t need them. Generations of opera lovers have been grooving on Wagner without speaking a lick of German; and adventurous Anglophone pop fans can get a kick out of Korean boy-band R & B, swoony chanson, or Italian diva-disco. It’s a marvelous property of music that meaning is secondary to the pleasures of melody — pleasures that transcend language.

All of which is by way of telling you how the Old Professor came to have one of those ”a-ha!” moments (is there an actual word for that? It seems that there must be) in an unexpected context. To undergo illumination without understanding. To hear, in a foreign-language pop song that I had previously experienced as a pleasant-but-meaningless stream of syllables, analogous to birdsong, a name. A name I recognized. A name I had not expected.

Los Fabulosos Cadillacs recorded ”El Matador” in 1994, as a bonus track for their compilation album Vasos VacÁos. I don’t think I heard it quite that early; but by the time it showed up on the soundtrack for the 1997 John Cusack vehicle Grosse Pointe Blank, ”El Matador” was in heavy rotation on Gyroscope, the now-defunct world music show that once aired on Boston’s WERS-FM, where — along with the tracks from the likes of Jovanotti, Mano Negra, Dubtribe Sound System, and the Buena Vista Social Club — it enlivened many a long homebound commute.

Los Fabulosos Cadillacs — El Matador

”El Matador” is itself a product of cross-cultural listening. Though hailing from Buenos Aires, the Cadillacs’ sound is grounded in Jamaican ska. The track’s deep Studio One bass-and-guitar skank is laid over the samba rhythms of a Brazilian street carnival, spiced with Afro-Cuban-style brass and singer Vicentico’s melodramatic, mariachi-tinged lead vocal. (Vicentico — whose full name is Gabriel Julio FernÁ¡ndez Capello — is married to film and television actress Valeria Bertuccelli, which I guess makes him, notionally, the Eddie Van Halen of Argentina.) With a monstrous gang chorus featuring both an ”Oh yeah” and a ”Hey hey,” it’s a stomping feel-good summertime jam of the first order.

I never would have taken it for a socially-conscious jam, though. And I certainly wouldn’t have imagined it would reference one of the most horrifying and tragic episodes in south American history.

But there it was, in the vocal breakdown before the second chorus: the name. Victor Jara.

And a whole flotilla of origami swans hove into view, scudding through the cunningly-folded ferns and reeds across a blue-paper lake.

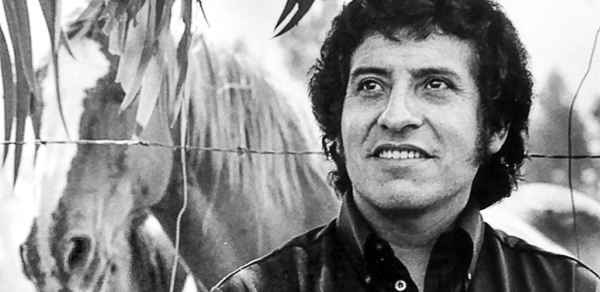

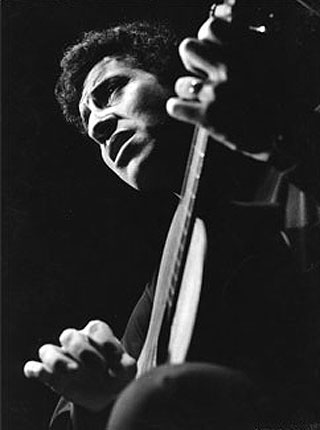

Songwriter, poet, musician and activist Victor Jara was a genuine hero — one of the artistic giants of South American history, a key figure in the development of a postcolonial cultural consciousness. Jara was born in Chile in 1931. After an early stint in the seminary and a hitch in the army, he took up a career in the theater; inspired by Chile’s rich heritage of music and folklore, he began writing poetry and songs, recording his first album in 1966.

In his brief career as a singer-songwriter, Victor Jara forged a sound that fell somewhere between Gilberto and Greenwich Village. His repertoire blended traditional material and original songs, all rendered in a sweet, lilting tenor. Over gentle Spanish guitar or ”El Condor Pasa”-style ensemble arrangements, Jara sang of lost love and dignity of labor, eulogized Pancho Villa and Che Guevara, even set the words of dissident poet Pablo Neruda to music. He also made explicit his connection to the North American folk revival , bringing songs by Peter Yarrow and Pete Seeger to the Spanish-speaking world. American folksinger Phil Ochs became a great champion of Jara’s music up north, after meeting and befriending Jara whilst touring South America.

Victor Jara — Plegaria a un Labrador (Prayer to a Laborer)

Chile in the 1950s and 60s, like many postcolonial societies, was profoundly stratified. A tiny minority benefited from crony capitalism and the old spoils system; the newly-emergent middle class was content with this status quo — so long as they got their slice of the pie — but the industrial and agricultural workers who formed the backbone of the economy were shut out of any prosperity. The rampant economic and social injustices led Victor Jara — along with many other bright, idealistic Chileans — to embrace communism. He became an outspoken supporter of the Unidad Popular, the leftist coalition led by Salvador Allende.

When the Unidad Popular won the Chilean presidency in a tightly-contested election, reactionary forces were terrified. Chile had enjoyed four decades of uninterrupted democracy — an exceptional record, given the general political instability and tradition of military dictatorships across the continent. But the prospect of a successful, democratically-elected Marxist regime in the Americas was too much; the Allende government could not be allowed to succeed.

A military junta, with the tacit (and occasionally not-so tacit) support of the US administration, began plotting to overthrow Allende. Elements of the Chilean government — notably economics minister Pedro Vuskovic — worked to destabilize Allende’s administration from within, flooding the country with paper currency and triggering massive inflation. Outside forces took action against Allende, too. Documents declassified in the 1990s show that the CIA covertly funneled money to right-wing groups to organize strikes and protests, disseminated anti-Allende propaganda, and even attempted to bribe the Chilean legislature.

On September 11, 1973, the junta implemented a full-on coup d’Á©tat that would ultimately see General Augusto Pinochet installed as dictator. Allende himself died during the overthrow; the military has always claimed it was suicide, but in all likelihood he was assassinated. The very next morning, paramilitary forces began to sweep the country, rounding up Allende supporters — many of them artists, intellectuals, and organizers — en masse. Public spaces were converted into makeshift prison camps where, hidden from the eyes of the world, Pinochet’s minions could torture and kill with impunity.

Victor Jara was plucked off the street on September 12 and imprisoned, along with thousands of others, in a soccer stadium. Four days later, his bullet-riddled body was found dumped on a country roadside.

Precisely what happened to Victor Jara in the Estadio Chile may never be known. A dramatic account of his martyrdom began to circulate in the years after his death. The details vary, according to who’s telling the story; but here’s the version that the late Pete Seeger used to give, transcribed from the 2010 film There But For Fortune, a documentary about Jara’s great friend Phil Ochs:

The army put several thousand students and professors, and Victor, all in a big soccer stadium. And they put a table in the middle of this stadium. They said, ”Put your hands on the table.” And they came down with rifle butts on his hands, til they were bloody pulps. And they said, ”Now sing for us, you cocksucker!” And he staggered to his feet, with his face white, and his bloody hands dripping; and he walked over to the stands and says, ”CompaÁ±eros, let’s sing a song for el comandante.” And waving his hands, his bloody hands, they sing the anthem of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity Party. And the whole stands — hesitantly — joined in with him. It was too much for the colonel. They opened fire with machine guns, sprayed the stands, and he was shot with many bullets in his back.

It’s a dramatic story, but almost certainly apocryphal. When formal charges were finally brought in 2008 — thirty-five years after Jara’s death — JosÁ© Adolfo Paredes MÁ¡rquez, an 18-year old army conscript at the time of the killing, laid out a narrative just as horrifying, but considerably less inspirational. Paredes testified that Victor Jara died out of sight, in the stadium’s locker room, from a single bullet to the brain, from a 9mm revolver loaded with a single round. According to Paredes, Jara was the sole and unwilling contestant in a game of Russian roulette; a low-ranking officer, Lt. Pedro Barrientos NÁºÁ±ez, repeatedly spun the revolver’s cylinder and put the gun to Jara’s head several times before finally hitting the loaded chamber. After Barrientos shot Jara, he ordered Paredes and another conscript to pump additional rounds into the body, presumably to obscure the exact manner of Jara’s death. The autopsy report indicates that he was struck by 44 bullets in all.

Pedro Barrientos, named as the triggerman in Jara’s murder, is a former career military officer. He was trained at the notorious School of the Americas, a US Defense Department facility at Fort Benning in Georgia, now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. After the fall of Pinochet, Barrientos emigrated to the USA and became a naturalized citizen; he is now 65 years old, and currently lives in Deltona, Florida. An international warrant was issued for his arrest in late 2012, but US authorities have thus far failed to comply.

Victor Jara’s music would not be heard in Chile for nearly 20 years. His songs were banned from the radio, and his albums disappeared from shops. The junta tracked down and burned whatever master tapes they could find. Not until after Pinochet’s ouster in 1990 was the ban lifted. But Jara’s music survived in samizdat cassettes, and his reputation grew by word of mouth. Over the decades, dozens of artists from Latin America and around the world have paid tribute, from those who knew him personally — like Ochs and Seeger — to folkie fellow-travelers like Bob Dylan, Christie Moore, and Holly Near, to international superstars like Springsteen, the Clash, and U2.

And Los Fabulosos Cadillacs. Argentina, let us not forget, is a country with its own tortured history of dictatorship and unrest. ”El Matador” turns out to be an imagined narrative of a political activist, hunted by the police. His nickname is a neat play on words. It’s used in English as a general term for a bullfighter, but the proper Spanish term is torero. ”Matador” comes from the descriptive title matador de toros. On its own, it simply means ”killer.”

And Los Fabulosos Cadillacs. Argentina, let us not forget, is a country with its own tortured history of dictatorship and unrest. ”El Matador” turns out to be an imagined narrative of a political activist, hunted by the police. His nickname is a neat play on words. It’s used in English as a general term for a bullfighter, but the proper Spanish term is torero. ”Matador” comes from the descriptive title matador de toros. On its own, it simply means ”killer.”

Me dicen el matador, nacÁ en Barracas

si hablamos de matar mis palabras matan

”They call me the Matador, born in Barracas” — a rough neighborhood of Buenos Aires, originally the site of slave quarters, later a district of slaughterhouses and tanneries; our revolutionary hero is again associated with the killing of cattle and bulls. But his weapon of choice is not violence, but poetry: ”You talk about killing — I kill with my words.”

But the cops are closing in; the Matador is holed up in a bare unfurnished room, ready to make a last stand. (It’s unclear to me, with my paltry Spanish, how much of what happens is real, and how much is in the Matador’s paranoid imagination. I never was much good with conditional tenses…)

Viento de libertad sangre combativa

en los bolsillos del pueblo la vieja herida

de pronto el dia se me hace de noche

Murmullos, corridas y golpe en la puerta,

llego la fuerza policial

The wind of freedom blows, and the militant blood is rising — but there are still old wounds in the hidden parts of town. And as the night falls, he hears — or thinks he hears — voices outside, then a flurry of knocks on the door, a sound that reminds him of bullfights (corridas).

And then the cops bust in, or he imagines the cops busting in, and he thinks of Victor Jara:

Mira hermano en que terminaste

por pelear por un mundo mejor

Que suenan, son balas, me alcanzan,

me atrapan, resiste, Victor Jara no calla

”Brother, they took you down for fighting for a better world.” He hears — or imagines — the bullets striking him. ”What a sound!” he thinks. He is trapped, but he resists: ”Victor Jara would not be silenced.”

In the aftermath, the Matador — like Victor Jara — becomes a folk hero: they talk about the Matador in all the hundred neighborhoods of the city.

No tengo por que tener miedo mis palabras son balas

balas de paz, balas de justicia

soy la voz de los que hicieros callar sin razon

por el solo hecho de pensar distinto, ay Dios

Santa Maria de los Buenos Aires, si todo estuviera mejor!

”I have no fear,” the narrator thinks, ”for my words are bullets; bullets of peace, bullets of justice. I am the voice of those who were silenced without reason, just because their way of thinking was different.” And he ends with an anguished prayer to God and the Blessed Virgin: ”If only everything were better!”

That’s a pretty broad, adolescent sort of prayer, a very rock n’ roll prayer — rock being an idiom that’s short on sophisticated social stances. There’s an essential naÁ¯vetÁ© to it, a big-screen earnestness worthy of Coldplay or, well, U2. Where Victor Jara could be resigned or ironic, his idealism grounded in the wisdom of a life fully-lived, Los Fabulosos Cadillacs are all youthful bombast; and the labor of translation makes the over-the-top melodrama — My words are bullets! Bullets… of peace! — all the more apparent to the Anglophone listener.

But it’s a hell of a lot of fun, and the image of the torero makes a nifty metaphor for the artist as socialist revolutionary — of the triumph of cunning and style over brute force. He tempts the crushing power of the bull, waving his brave red flag and inviting the charge — then evades, and avoids, and wears his enemy down. It’s not just about winning. There’s an aesthetic element to his triumph; the beauty of the performance is as important as the kill. He outwits the lumbering beast, lures it, maneuvers it to the spot where he wants it, using its own great inflexible strength against it.

It’s one of those songs that you hate yourself a little for liking it so much — it’s not a guilty pleasure, exactly, but a song that gives you that feeling — you know the one — the feeling of gladly giving yourself over to the artless exuberance of the thing, because even if it’s ham-fisted and awkward, its heart is in the right place, and you can appreciate the blood-pounding velocity of it even as you smile fondly at its overreach.

You know. That feeling. There’s got to be a word for that. Though probably not in English.

Comments