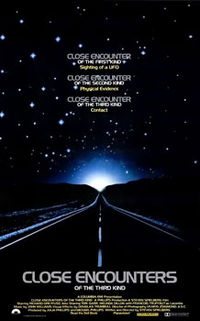

The summer of 1977 gave us Star Wars, but later that year TV ads started cropping up for something else entirely — something involving UFOs, with a “first,” “second,” and “third kind” terminology I wasn’t familiar with. What the hell is this? I wondered. A documentary? Or one of those cheesy “Schick Sunn Classic Pictures” pseudo-documentaries about Noah’s Ark or Bigfoot?

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/iJ195AlcurA" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

It turned out that in the realm of 1977 sci-fi blockbusters, Star Wars was not alone.

I wanted to see this film so badly I couldn’t stop talking about it. One day my parents took me for a little drive and soon we pulled into the parking lot of the Century 5 in Pleasant Hill, California, with its huge, domed main auditorium. Writer-director Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind had just opened, and my parents were surprising me by taking me to see it.

At the time I knew very little about sound systems, but of all the theaters we normally went to in the East Bay, “the dome,” as we called it, was the best. Close Encounters begins in blackness, then suddenly cuts to the bright daylight of the Sonoran Desert. John Williams’s accompanying music begins quietly, but he hits the transition to the desert with a massive full-orchestra stinger, which shook the theater.

The opening scene involves an international science team led by Claude Lacombe (played by French director FranÁ§ois Truffaut), who discover in the Sonoran a squadron of airplanes that went missing in 1945 — over the Bermuda Triangle.

I was hooked. And I left the theater that day thinking that Close Encounters was the best film I’d ever seen. (Since then it’s been relegated to the #3 spot on my list of all-time favorites, behind Spielberg’s Jaws and E.T.)

Richard Dreyfuss plays the film’s protagonist, Roy Neary, an “everyman” who has a close encounter with a UFO, as do several other characters in the film, notably single mom Gillian (Melinda Dillon) and her three-year-old son, Barry (Cary Guffey). Roy and Gillian begin to have similar visions of a mountain-shaped object, which leads them and everyone else who’s had a close encounter to Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, the place the aliens have apparently chosen to formally introduce themselves to the human race.

Richard Dreyfuss plays the film’s protagonist, Roy Neary, an “everyman” who has a close encounter with a UFO, as do several other characters in the film, notably single mom Gillian (Melinda Dillon) and her three-year-old son, Barry (Cary Guffey). Roy and Gillian begin to have similar visions of a mountain-shaped object, which leads them and everyone else who’s had a close encounter to Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, the place the aliens have apparently chosen to formally introduce themselves to the human race.

However, unlike in most science fiction films, the aliens aren’t here to conquer us or eventually “serve” us from their extraterrestrial cookbooks. Rather, they’ve come to our planet to communicate with us through music.

Composer John Williams wrote endless variations on the famous five-note theme heard in the film. He thought he could do better with seven, but Spielberg insisted on five, even though he was unable to explain why. When Williams finally found the right five, he understood that seven would have sounded like a melody, while five notes are more like a signal.

Close Encounters was originally scheduled to be released in the summer of ’78, but Columbia Pictures decided to put it out ahead of schedule in November of ’77. Spielberg felt it wasn’t quite finished, though — there was still some tweaking he wanted to do in terms of editing and pacing. Also, the studio’s rush release meant there wasn’t enough time to complete a major sequence: the science team’s discovery of a giant ship in the Gobi Desert (the S.S. Cotopaxi, a real vessel that sank near the Bermuda Triangle in 1925).

A few years later Spielberg was given the opportunity to go back and “finish” Close Encounters, but he had to compromise with the studio: he agreed to shoot a new sequence for the film’s finale that would take place inside the aliens’ mother ship. Though he’d never wanted to show the interior of the ship, he agreed to Columbia’s request so that he could fine-tune the rest of the film.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Special Edition was released in the summer of 1980. In addition to the new footage of Roy stepping inside the mother ship, the discovery of the Cotopaxi in the Gobi Desert was inserted, plus a scene showing Roy having a nervous breakdown in his shower while fully clothed.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/WrzCIf9xrME" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

More important was what was now missing from the film: an early scene showing Roy at his power-company job, a military press conference at which a farmer (Roberts Blossom) claims to have seen Bigfoot, and a critical sequence that showed Roy throwing dirt and rocks into his house so he could sculpt his vision of the mountain-shaped object right in his living room. This sequence was especially missed, as it was the main motivation for Roy’s wife, Ronnie, (Teri Garr), to take their three kids and leave him.

For many years, the “Special Edition” was the only version of Close Encounters that was available. Then in 1990 Criterion released a laserdisc box set featuring, at long last, the original 1977 version. It also gave viewers the option of programming in the scenes that were exclusive to the special edition. It wasn’t seamless, of course — there was a one-second gap every time the program switched to a different chapter stop. This led me to do one of the coolest — and, admittedly, most anal — things I’ve ever done: I painstakingly assembled on a Super-VHS tape my own ultimate edition of Close Encounters that included all of the existing footage, minus the stuff inside the mother ship (I agree with Spielberg that it should never have been shown).

My S-VHS tape was finally rendered useless in 1998, when Spielberg assembled the definitive “Collector’s Edition,” known also as “the director’s cut.” It’s still missing some footage from the 1977 release, such as Roy at the power station, but it’s the best version out there. Fortunately, the recent DVD and Blu-ray “Ultimate Edition” feature all three versions of the movie. When I sit down to watch I usually go for the director’s cut, but it’s nice to occasionally revisit the original or even check out the ending of the Special Edition, and venture one more time inside the mother ship with Roy Neary.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b7fd6a11-3588-4fd0-a78a-c86dda45ba88)

Comments