With Super Bowl Sunday coming up, I figured it was time to pop in my DVD of Black Sunday (1977) once again.

With Super Bowl Sunday coming up, I figured it was time to pop in my DVD of Black Sunday (1977) once again.

Six years before author Thomas Harris unleashed Hannibal Lecter on the world, there was his first novel, Black Sunday, a 1975 thriller about the Palestinian Black September movement and a terrorist plot to kill thousands of innocent people at the Super Bowl. It would turn out to be his only novel (to date) not featuring Dr. Lecter, and the first of his books to be adapted for the big screen. For a novelist, Harris has an impressive record of film adaptations: all five of his books have been adapted into a total of six movies — 1981’s Red Dragon was filmed by director Michael Mann in ’86 and released as Manhunter, and in 2002 Rush Hour‘s Brett Ratner adapted it again, this time keeping the book’s title intact and staying (mostly) faithful to the source material.

John Frankenheimer was the perfect director to take on Black Sunday, having made many excellent thrillers in the ’60s, including The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seven Days in May (1964), and Seconds (1966). But in my opinion Black Sunday turned out to be his last great film. The quality of his films declined over the next two decades, with such mediocre offerings as 1979’s Prophecy (“The monster movie,” according to the poster) and the sleazy 52 Pick-Up (1986). Frankenheimer’s 1998 film Ronin was considered by some to be a return to form, but it still paled in comparison to his earlier work.

The screenplay for Black Sunday was written by Ernest Lehman (North by Northwest), Kenneth Ross (The Day of the Jackal), and Ivan Moffat (Giant) — a powerful trio of screenwriters, for sure, particularly Lehman, who in 2001 became the first screenwriter to receive an honorary Oscar for his work.

Both the screenplay and Harris’s novel do an amazing job of creating realistic characters who feel compelled to commit acts of terrorism, whether their reasons are political (Marthe Keller’s character, Dahlia Iyad) or psychological (Bruce Dern’s blimp pilot, Michael Lander). The film smartly spends as much screen time with the people who are trying desperately to pull off their mission as it does with the team trying to put an end to it, led by Israeli Mussad agent Kabakov (Robert Shaw) and FBI agent Corley (Fritz Weaver).

The acting is terrific all around, but it’s hard not to single out Dern’s portrayal of a Vietnam POW survivor, a seriously troubled man with a failed marriage who isn’t allowed to see his children anymore. In one scene Michael confides to Dahlia his true motivation for wanting to carry out their plan after he learns he’s been replaced as the blimp pilot for the big game (“I was just going to give this whole son-of-a-bitching country something to remember me by!”). Another poignant moment has him proclaiming his love for Dahlia in a Miami hotel room the night before their suicide mission.

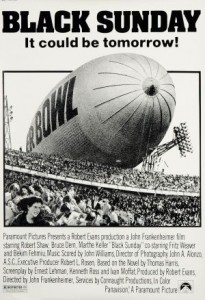

Black Sunday‘s finale is an exciting sequence in which Michael attempts to use the Goodyear blimp to detonate a device that will propel 222,000 darts into the Orange Bowl stadium’s crowd. I don’t even want to know how much the NFL got paid for licensing fees — Paramount was allowed to film some footage at the actual Super Bowl X game on January 18, 1976, so it’s the real Pittsburgh Steelers versus the real Dallas Cowboys, complete with Roger Staubach, Terry Bradshaw, and all of the other regular players. Pat Summerall and Tom Brookshier (who died last Friday at the age of 78) also appear in the film; they were the actual commentators who did the play-by-play for the game’s television broadcast. Goodyear even granted permission for Paramount to use the actual Goodyear blimp, though the studio wasn’t allowed to use the tire company’s logo in any of its print advertising for Black Sunday; thus, a portion of the words “Super Bowl” appear on the side of the blimp on the film’s poster.

All of these elements add realism to the tense finale, which provides some amazing aerial stunt work as Agent Kabakov dangles from a helicopter in pursuit of the blimp. Also propelling the action is an exciting ostinato-driven score by John Williams; two months after Black Sunday hit theaters, his score for Star Wars helped change the world of film scoring for years to come.

Okay, now I’m ready for the big game. Like real-life Miami Dolphins owner Joe Robbie says in the film, after Kabakov suggests canceling the game, “That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard. Cancel the Super Bowl? That’s like canceling Christmas!”

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=074ee75f-e557-43e7-a7b0-2d3f571d2c63)

Comments