“The film which you are about to see is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin. It is all the more tragic in that they were young. But, had they lived very, very long lives, they could not have expected nor would they have wished to see as much of the mad and macabre as they were to see that day. For them an idyllic summer afternoon drive became a nightmare. The events of that day were to lead to the discovery of one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.”

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/5wdIwp0Vsc0" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

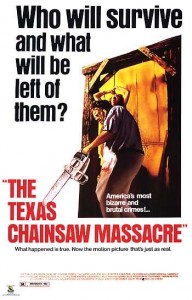

With this opening narration, voiced in a matter-of-fact manner by John Larroquette, the tone is set for one of the most notorious independent horror films of the ’70s. At the time, and even to this day, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) has a reputation of being a splatter-fest of over-the-top gore — and it turns out that’s really not the case. Instead the film’s violence is mostly suggestive, much of it left to one’s imagination, achieved through skillful filmmaking, sound design and editing.

The film’s director Tobe Hooper was a college professor at the University of Texas at Austin and also working as a documentary cameraman when he assembled an unknown cast of mostly teachers and students to shoot the screenplay he had co-written with Kim Henkel. As for the film’s budget, I’ve seen figures anywhere between $60,000 and $140,000. However it’s reported, the film was extremely low-budget, but this is in no way a hindrance — the 16mm look gives the film a documentary feel, which combined with the film’s false claim of being based on a true story, only adds to the overall effect.

This is the kind of horror film in which a certain mood is established, a constant and unrelenting feeling of dread that permeates throughout. Immediately after the opening narration, we catch brief glimpses of badly decomposed corpses that appear to be lit with flashes from a camera flash bulb (accompanied by very odd sound effects that were later used in the trailer for the 2003 remake). Then in the light of morning we see a that a full human corpse has been dug up and put on grisly display in a graveyard, over which we hear a radio news report of grave vandalism in a small rural Texas community.

This is the kind of horror film in which a certain mood is established, a constant and unrelenting feeling of dread that permeates throughout. Immediately after the opening narration, we catch brief glimpses of badly decomposed corpses that appear to be lit with flashes from a camera flash bulb (accompanied by very odd sound effects that were later used in the trailer for the 2003 remake). Then in the light of morning we see a that a full human corpse has been dug up and put on grisly display in a graveyard, over which we hear a radio news report of grave vandalism in a small rural Texas community.

The first murder in the film is a superb showcase of editing and sound design. Two teenagers, Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn) stumble across an old house. Kirk hears odd noises and steps inside while Pam waits outside. It is inside the house where Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) first appears, wearing an apron and a mask that seems to be made from human skin. Leatherface bashes Kirk in the head with a mallet, drags him into a back room and slams shut a metal door which makes a thunderous sound when it closes. Also heard in this moment is the ambient atonal electronic score by Wayne Bell and Tobe Hooper, sounding more like a part of the sound design than a traditional music score. The end result is such a feeling of finality when that door closes, a cold feeling of death.

Outside the house, Pam rises slowly, the camera at a low angle so the house looms ominously larger-than-life as she approaches. Her death is not a pleasant one either, as Leatherface hangs her on a meat hook through her back and leaves her dangling there. Again, no gore is shown — we never actually see the hook penetrate her skin. Letting the very thought linger in our minds only makes it all the more horrific — a concept that no other film in the series, including the remake, seem to grasp.

The contribution of cinematographer Daniel Pearl is evident throughout, but his work really shines during the intense chase sequence when the last girl standing, Sally (Marilyn Burns) is relentlessly pursued by Leatherface into the night. Pearl shoots many of these shots with a long lens as Sally runs screaming towards the camera while Leatherface slowly gains on her. Pearl went on to serve as cinematographer for many music videos, the remake of Friday the 13th (2009) and ironically 2003’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake.

The film’s horror gets cranked up to 11 during the climactic dinner scene in which lone survivor Sally is forced to sit at the table with Leatherface and his entire crazy-ass family. The insanity is captured with several minutes of laughing, taunting, screaming and extreme close-ups of her eyes (which Hooper seems to have a fascination with). In fact while I am certainly aware of the controversy over who really directed Poltergeist (1982), Tobe Hooper or producer Steven Spielberg, I would certainly say that Hooper definitely left his stamp on that film. All you need to do is re-watch the moment towards the end where Craig T. Nelson confronts James Karen about the headstones (for the eye close-ups) and also the moment where Nelson comes face-to-face with “The Beast” (for the editing reminiscent of several scenes in Chain Saw).

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had a great run on the drive-in movie circuit and ended up grossing over $30 million over time, making it one of the most successful independent films of all time. It was surpassed by John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978, the success of both films being a clear indication of why the slasher genre took off in the early ’80s.

I’ll leave you now with the spoiler-heavy trailer, where we can easily see what drew people in the first place — that and the title itself of course. Back when it was playing at my local drive-in, when I was 10 years old, I remember thinking “Who would see something like this?” while at the same time kind of wanting to see it.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/285ImXTYdsg" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Comments