Can a song change the world?

Popular music has always been looked on as something of a disposable pleasure: reflective of its times, sure, but meant to be played among company in a drawing room, or sung with friends over a car radio or danced to in a club. That a popular song might comment on society with such originality and power that it becomes a historic event in itself seems little short of hubris. Yet artists of every background and political persuasion have taken on the challenge, and we call the resulting works ”protest songs,” a term that calls to mind earnest folkies singing at rallies or in coffeehouses, totems of past struggles invariably viewed through a haze of nostalgia and self-congratulation.

This, though, doesn’t merely diminish those works by detaching them from the events and circumstances that made them so vital; it threatens to relegate an entire sphere of art to little more than a historic fad. Call them protest songs, political songs, message songs or topical songs, they make up a vital avenue of public debate, one with considerable power to inform us even after the issues that inspired them have faded from the headlines. In choosing the greatest protest songs of all time, we at Popdose sought to consciously go beyond the stereotypes and cast a wide net. We looked for songs that aimed a critical eye on the world they were made in, songs that posed a question or took a stand or set an example. You’ll find most of the genre’s acknowledged classics on our list, as well as (we hope) some left-field choices that get you thinking not just about the topics they address, but about all the things a ”protest song” might be in the first place.

Can a song change the world? It’s a difficult question to answer. What a song undoubtedly can do is to help steer the cultural conversation, to either reaffirm or challenge what we’re willing to accept as just and right. A song may or may not change the world, but it can certainly change the way you think about it — which, in the end, might be one and the same thing.

Enjoy our list, and feel free to lodge any protests in the comments below. — Dan Wiencek

100. ”I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” – Country Joe and the Fish. Issue: Vietnam War

For every poignant and heartful yearning, for every bloodstained couplet, there is a mirror version that speaks to the hopelessness of the moment. Dripping with sarcasm and black humor, this one and only cultural touchstone by Country Joe and the Fish was the song that stuck to Woodstock Nation. While the hippies, flower children, protesters and hornballs acted out in equal measure during the historic concert event, most of the young men in the audience had this specter of death standing next to him. It was called the draft, and unless circumstances, deus ex machina or Canada intervened, their country was going to pluck them up, drop them off in the jungle, and there’d be nothing they could do about it. No choice. No agency. If they were lucky, they’d come home in one or some piece. If they were unlucky, they’d die. Somewhere in between, they might be captured as a prisoner of war, tortured but otherwise make it back home, only to be mocked for his service by a political campaigner. Country Joe McDonald clearly hadn’t a clue that the last bit would happen, but then again, why wouldn’t it? Lives, it seemed, were cheap as toilet paper, something that the concert latrines seemed in short supply of. It’s an extremely glib song. It’s not necessarily a good song. But it spoke to that hopelessness that hovered above even the heaviest smoke-stoned bliss out. You will be scooped up. You will go to war. You will do what you’re told. You will kill the wives and children of your enemies. You will waterboard. You will call it your honor and duty. Nothing really changes. — Dw. Dunphy

99. ”Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys” – The Equals. Issue: Racial integration

Long before he rocked us all down to Electric Avenue, Eddy Grant was decked out in velvet and ruffles, cranking out psychedelic bubblegum as the driving force behind the Equals. Formed in 1965, this mixed-race combo — their very name was a provocation — brought an Anglo-Caribbean sensibility to the swingin’ London sound. They are a bit underrated today; ”Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys” is on this list only because it was my personal #1. But it was the Equals who first recorded ”Police on My Back,” later famously covered by the Clash. And this 1970 single is perhaps their finest moment: urgent, apocalyptic, and bracingly weird, with a deep, deep groove and a powerhouse lead vocal from Derv Gordon. — Jack Feerick

98. ”I Can’t Get Behind That” – William Shatner and Henry Rollins. Issues: Advertising, language, conservation, religion, highway safety, public nuisances, obesity

Protest songs are typically about big things — war, racism, injustice, what have you — but life is made up mostly of little things, and it’s that recognizable urge to make a big deal out of very little that powers ”I Can’t Get Behind That.” Sounding like Jerry Seinfeld whacked out of his box on bath salts, William Shatner and Henry Rollins roar, carp and whinge over a ferocious percussion track about all the little things that really piss them off, from the imminent extinction of tigers to student drivers to, well, a fat ass. For best results, play during your morning commute. — Dan Wiencek

97. ”Taxman” – The Beatles. Issue: Taxation

One of George Harrison’s most powerful and propelling Beatles-era tracks, this was a very direct and scathing indictment of British tax laws during The Beatles’ heyday — the outrageous notion of literally taking the majority percentage of money earned, especially by performers. The British government was bleeding the people dry and Harrison, for one, was not amused. — Rob Ross

96. ”The Death of Emmett Till” – Bob Dylan. Issue: Lynching

Emmett Till didn’t die because he was a black man whistling at a white woman. Emmett Till didn’t die because white men thought he whistled at a white woman. Emmett Till died because white men wanted to believe he whistled at a white woman. In a culture where evidence is never asked for and any excuse to visit the unthinkable is fair ground, this is what happens. Anyone can invent a justification to attack and then claim they were justified in attacking. A society that condones this veneer of evil bathes in it. Fortunately, the preeminent firebrand of his day had no interest in keeping silent. Now, if you read some of Bob Dylan’s memoirs, you can quickly get the impression that he is as much consumate opportunist as showman. I hope that, in this case, his sincerity outmatched his strategic thinking. — Dw. Dunphy

95. ”Border Song” – Elton John. Issue: Prejudice

Those early Elton John songs never actually made much sense, did they? Like, who the heck is Alvin Tostig anyway? (Answer: Levon’s dad, but it sounds so much more portentous when Elton sings it.) Both he and lyricist Bernie Taupin were having a bit of fun with wordplay in the early days, when mood often trumped meaning. But “Border Song,” that’s another thing entirely. Taupin knew damn well what he was trying to say, and in Elton’s angelic gospel-laden voice, it couldn’t be more clear. How do you describe the message? “You must be carefully taught?” “You must unlearn what you have learned?” Rather, maybe the echo chamber of your tribe is, in fact, wrong. Maybe you’ve been feeding on the reflected noise too long. Maybe you need to get woke. Or:

I’m going back to the border

Where my affairs, my affairs ain’t abused

I can’t take any more bad water

I’ve been poisoned from my head down to my shoes

Holy Moses I have been deceived

Holy Moses let us live in peace

Let us strive to find a way to make all hatred cease

There’s a man over there what’s his color I don’t care

He’s my brother let us live in peace

— Dw. Dunphy

94. ”Only a Pawn in Their Game” – Bob Dylan. Issues: Assassination of Medgar Evers, racism

In December of 1963, Bob Dylan shocked the doyens of the Old Left when, in the midst of accepting an award from them, he let slip with a jaw-dropping confession: ”The man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where — what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too — I saw some of myself in him.” The agitators and activists who booed him obviously hadn’t been listening too closely, for throughout the previous fall Dylan had been singing ”Only a Pawn in Their Game,” which plainly demonstrated that his politics defined easy pigeonholing. Using the assassination of NAACP activist Medgar Evers as a springboard, Dylan decries not the murder but the self-perpetuating forces that manipulate and consume the disadvantaged to maintain their own power; to Dylan, Evers’ assassin is merely a different kind of victim, a pawn in a game he doesn’t even know he’s playing. Thus are the marginalized turned against one another, never realizing whose interests they are truly serving. Sound familiar? — Dan Wiencek

93. ”T.V. ”Party” – Black Flag. Issues: Apathy

Black Flag’s one-off novelty tune was the couch potato version of the Beasties’ kegger anthem ”Fight For Your Right (To Party).” Several versions of this song exist, each with different TV references, including the most famous one from the Repo Man soundtrack. — Keith Creighton

92. ”It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” – Bob Dylan. Issues: Corruption, hypocrisy

Bob Dylan had supposedly moved beyond writing ”protest songs” when he penned this blistering masterpiece in the summer of 1964. This is Dylan at his most poetic and his most despairing, as he takes in a society that seems irredeemably corrupt on all sides: “Old lady judges watch people in pairs/Limited in sex they dare/To push fake morals, insult and stare/While money doesn’t talk, it swears/Obscenity, who really cares/Propaganda, all is phony.” Yet even at his darkest, Dylan finds consolation in the prospect that isolation from society is its own kind of freedom: ”And though the rules of the road have been lodged/It’s only people’s games that you got to dodge/And it’s alright Ma, I can make it.” — Dan Wiencek

91. ”Volunteers” – Jefferson Airplane. Issue: Revolution

We think of political change as coming from a place of anger. But though the atmosphere of ”Volunteers” is raucous, maybe even dangerous, it crackles with joy and enthusiasm. Ragged, righteous harmonies proclaim, ”We are volunteers of America!” — casting revolution as a patriotic duty. What’s interesting, and kind of beautiful, is the way the song tacitly endorses a continuity of change. The generation gap is acknowledged not in the sense of pitting old against young, but in passing the torch and continuing the work. In every generation, the youth get their chance to serve the country they love. This is our time. This is our country. This is our service. Thank you; we’ve got it from here. — Jack Feerick

90. ”Finest Worksong” – R.E.M. Issue: Apathy

As with most early R.E.M. songs, Michael Stipe’s lyrics here lean toward the abstract. The clearest line, ”What we want and what we need has been confused,” stands out and forces us to question what we’re working for. Let’s get to work, Stipe sings, but let’s set some priorities for a change. — Beau Dure

89. ”Paint a Vulgar Picture” – Smiths. Issue: Music industry

A dead pop star, especially one with a vault of unreleased material, is a way more valuable asset to record labels than a living one. No costly PR scandals, swank mansions, entourages or tour riders to deal with. At the dawn of the re-release-heavy CD era, The Smiths lifted the curtain on how deftly the industry can pick a carcass clean with extra tracks and a tacky badge. — Keith Creighton

88. ”Wake Up Everybody” – Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes. Issues: War, drugs, education, poverty, health care

Some songs are difficult to write about, and this is definitely one of those. “Wake Up Everybody” is a call to action, or multiple actions, but it is also so damn pretty. Performed by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, sung by the irrepressably soulful Teddy Pendergrass, and written by Gene McFadden and John Whitehead (of “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now” fame) and Victor Carstarphen, and produced by Gamble & Huff … you can quickly lose the thread. It’s not like Marvin Gaye and the What’s Going On album where, even at its most tender, the urgency never wavered. I’m not knocking “Wake Up Everybody,” mind you. It’s a fantastic song with a fantastic message. I just wonder if, more often than not, people didn’t fully take in that message because it was so expertly encased in a classic tune. — Dw. Dunphy

87. ”I Shot the Sheriff” – Bob Marley & the Wailers. Issue: Injustice

Where ”Get Up Stand Up” is a direct cry against injustice, ”I Shot the Sheriff” uses the format of the protest song to teach a powerful lesson in personal integrity. The song’s luckless protagonist — a former prisoner or slave, by the sound of it — shoots down the tyrannical Sheriff John Brown but not, he insists, the deputy. He believes his crime is justified, but is prepared for the consequences regardless of the verdict: ”If I am guilty, I will pay.” ”I Shot the Sheriff” is ultimately about upholding our own standards of decency in the face of injustice and unfairness — while still defending ourselves from the Sheriff John Browns of the world. — Dan Wiencek

86. ”Peace Train” – Cat Stevens. Issues: War, conflict

If you’ve made it to this point, you’re probably looking for a patch of blue sky in among all this gloom. Well, that’s the nature of protest music. You’re staring at ugliness, injustice, and hatred and making it known you don’t find it acceptable. But that’s not always how a protest needs to manifest. Sometimes you just need to take someone’s hand, particularly someone very different from you, and recognize all the physiological similarities, the emotional similarities, and of course the differences. Then you say, “Those don’t matter,” and you both jump on the peace train. Is it naive? Maybe. Is it overly idealistic? Certainly. But sometimes you have to force your dominant cynic to sit down when you stand up for other, better things. — Dw. Dunphy

85. ”War Pigs” – Black Sabbath. Issue: War

Oh, you want a demonic rite from Black Sabbath? Here it is. But your generals are the witches, summoning evil power to keep the war machine turning while — as in “Fortunate Son” — making sure the poor and downtrodden are on the front lines for the amusement of others. Ozzy, Iommi, Geezer and Bill Ward are the Four Horsemen here, with martial, galloping riffs to herald a final judgment that won’t be too kind to the alleged patriots. — Beau Dure

84. ”Fear of a Black Planet” – Public Enemy. Issue: Racism

A lot of discrimination is based on the fear of loss of power. That’s so simple, isn’t it? We all know that. But Public Enemy turned it into a rap, and added a new fear to the list of fears that too many white people have about black people. Too bad. — Ann Logue

83. ”Big Brother” – Stevie Wonder. Issue: Racism

Turning a critical eye towards the politicians that use empty promises (“Make America White Great Again” anyone?) to rally the poor and disenfranchised as so much political capital, “Big Brother” lays it all out. “I live in the ghetto, you just come to visit me ’round election time” is a charge that could be levied at either side of the aisle. Here’s hoping Stevie didn’t get it all right, as the song closes on this note: “You’ve killed all our leaders/I don’t even have to do nothing to you/You’ll cause your own country to fall.” Goddammit. — Michael Parr

82. ”Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore” – John Prine. Issue: Vietnam War

Symbols really mean things. Symbols actually matter. Very often symbols are used incongruously or as a cover. Think of that guy in the massive pickup truck, the one with the smokestacks belching black soot, the one with the American flag or flags flapping in the dirty backspray. What is ordinarily used as a reflection of pride or patriotism, or even in memorial, is in this context little more than a backward version of “fuck you.” (Incidentally, the guy in that vehicle will beat you down for burning a flag, even though he’s thisclose to doing it himself with his stunt.) While John Prine’s tune is very much a part of the anti-Vietnam War movement, it’s underlying truth can stand as proxy for any war, and any time you want to deflect a hard, difficult decision. Many young men went to Vietnam and died for their country. Many came home with scars of every kind, inside and out, and were demonized. No amount of “We’re the right ones because we said so, and these symbols we’re drowning in justify our righteousness,” can actually undo anything. It makes you feel good to keep those flag decals coming. It shows you just how good an American you are, because you have a lot of flags. But are you acting in righteousness or playing a role? And when your role is done, will there be room in your afterlife, or will it all be full-up with the victims of your capitulation? Or … you like to say “Make America great again,” but have you done anything — anything at all, hold a door for someone, be polite to your neighbor, not give another driver the finger even though you really want to — to actually make America great? Or did you merely vote for some guy, wash your hands of personal responsibility and sacrifice, and go home to yell at the kids? Symbols mean something, and sometimes they say things about you that you’d rather not have been said. — Dw. Dunphy

81. ”George Bush Doesn’t Care about Black People” – The Legendary K.O., sampling Kanye West. Issue: George W. Bush

It’s easy to hate Kanye, and yet, the man has written and produced some incredible songs. One of the most amazing moments in live television took place in 2005, at a telethon to raise money for Hurricaine Katrina victims. Mike Myers read the cards. Kanye West said what was on his mind: “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” Myers looked like he had been hit by a truck — a bad move for an improviser — and the camera quickly cut away. The Legendary KO rapped about the problem over West’s “Golddigger.” The notoriously thin-skinned West never complained, and the world got to hear a great and real piece of protest music. — Ann Logue

80. ”Games Without Frontiers” – Peter Gabriel. Issue: War

Gabriel’s first two solo discs post-Genesis represented a step away from the prog-rock that made his name, but were still recognizable as rock records. His third LP, though, was an altogether bleaker and more brutal affair. But behind the disorienting rhythms and the cascades of electronic noise you could hear Gabriel — after years of writing songs from inside elaborate fantasy frameworks — reengaging with the world outside. ”Games Without Frontiers” looks at geopolitics through a lens of whimsical dread, Kate Bush’s creepy-doll backing vocals whispering eerily over the tick-tock beatboxes, squelchy synth bass, and deceptively jaunty whistling. It’s a knockout. — Jack Feerick

79. ”Bangla Desh” – George Harrison. Issue: Famine relief

I think my admiration for George Harrison doubled because of The Concert For Bangla Desh and the single “Bangla Desh” which kicked off the whole thing. If “Do They Know It’s Christmas” was the match that eventually lit Live Aid, then this was likely where that spirit of responsibility came from. By no means do I suggest that “Bangla Desh” is the first time a celebrity has become a spokesperson for a cause and, subsequently, brought awareness forth from nothing. But this was not a typical concert. The song was not a typical call to action. It was very pointed and very focused. And it was from a Beatle. Sure, John Lennon was doing his part post-breakup, focusing on peace awareness, writing tracks like “Imagine” and “Power To The People” (also found on this list), but these were ideological and occasionally abstract. They shouted “Use your personal power, reject war, reject bigotry and separation.” Worthy thoughts, indeed … but hard targets to nail down. George was on point. These are starving people, displaced refugees, running from war, running from cruel twists of nature (the destructive Bhola cyclone of 1970). It is one thing to hate the war and to feel awful when the world strikes back in the form of disasters, but we must also protect the victims. Once again, our modern myopia has caused us not to see the examples of the past, and I often wonder how different things might have been had George still been with us during the Syrian refugee crisis. Perhaps things wouldn’t have been diifferent at all. — Dw. Dunphy

78. ”Dear Mr. ”President” – P!nk. Issue: George W. Bush

With her star rising in the pop world, P!nk did the remarkable and released a song that speaks out against President Bush, an act that got the Dixie Chicks banned from country radio. But P!nk’s conscience was more important than record sales. She used her popularity to reach the masses with a protest song that is a haunting, modern classic. Backed only by the fantastic Indigo Girls on guitar and harmonies, P!nk blasts Bush’s policies on No Child Left Behind, homelessness and gay rights. Like the best folk songs, it sounds pretty as flowers, but a closer listen reveals that P!nk uses those flowers as daggers to take on her president and call out his hypocrisies. — Scott Malchus

77. ”1000 Deaths” – D’Angelo. Issues: Racism, police brutality

D’Angelo’s long awaited third record was supposed to be released in 2015, but then Ferguson happened, and Eric Garner, and … well, it keeps on happening. This frantic track is “Fight the Power” for 2015, reading straight from Malcom X’s By Any Means Necessary, and including this speech by Fred Hampton: “Black people need some peace, white people need some peace. And we are going to have to fight, we’re going to have to struggle, we’re going to have to struggle relentlessly to bring about some peace because the people that we’re asking for peace, they’re a bunch of megalomaniac war-mongers, and they don’t even understand what peace means. We’ve got to fight them, we’ve got to struggle with them to make them understand what peace means.” — Michael Parr

76. ”Ghost of Tom Joad” – Bruce Springsteen. Issue: Economic change

This song made its debut in 1995, on Springsteen’s acoustic record with the same title; it came raging back to life in 2014 with guitar from Tom Morello. No disrespect for mid-nineties Boss with the Woody Guthrie obsession and the slightly douchey ponytail, but I’ll take the latter; if the original is a slow drive through the dry lands of American denial, the remake drops a match into the crackling brush and floors it through the flames. — Matt Springer

75. ”Meat is Murder” – The Smiths. Issue: Animal cruelty

It’s death for no reason and death for no reason is murder … well technically the reason is to feed people. Carnies to be exact. But Moz and Co. certainly made a good point and the gorgeous track certainly paved the way for my generation to at least advocate for the ethical treatment of animals even if we thew a few organic, grass-fed, humanely killed ones on the grill from time to time. — Keith Creighton

74. ”Ronnie Talk to Russia” – Prince. Issue: Cold War

The wall came down and we had a good 20-year run before the Cold War started heating up again. Prince’s plea to Reagan from the Controversy album takes an ironic twist with modern listening because Bubba Trump apparenty talks to Russia too much. Me thinks by this time next week, Donny will have already faxed our nuke codes to the Kremlin. — Keith Creighton

73. ”In the Ghetto” – Elvis Presley. Issue: Racial inequality

Elvis’s 1969 comeback hit (written by Mac Davis) is the very epitome of feckless white liberalism, a saga of intergenerational poverty and criminality delivered with the solemn tones and sociological detachment of a nature documentary, and without consideration of the narrator’s own role in perpetuating the cycle. There’s nothing cynical in it — the trembling strings and Elvis’s own booming sincerity make the good intentions — but in its patronizing pathologization, ”In the Ghetto” comes off like the Moynihan Report set to music. — Jack Feerick

72. ”I Don’t Like Mondays” – The Boomtown Rats. Issue: School shootings

While not a “protest” song per se, this groundbreaking, powerful piece for its time (1979) foreshadowed the epidemic that has plagued the United States since the early ’90’s: school shootings. The Boomtown Rats laid out a chilling and precise glimpse at what would become painfully regular with the notorious massacres at Columbine, Westside Middle School and Sandy Hook. — Rob Ross

71. ”Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)” – Pink Floyd. Issue: Education

Maybe Roger Waters’ English schooling experience didn’t include that Robert Frost poem questioning the proverb that good fences make good neighbors. In Waters’ cynical eyes, the ”education” on offer did little but turn out fodder for the machine, a bunch of docile participants in a regimented society with thick walls between social classes and indeed any ”other” out there. — Beau Dure

70. ”Southern Man” – Neil Young. Issue: Racism

With its stark imagery of oppression and violence, including burning crosses and cracking bullwhips, ”Southern Man” hearkens back to ”Strange Fruit” in its refusal to look away from the ugliest aspects of American racism. The fact that Young was Canadian, with admittedly no more firsthand knowledge of the South than the average New York Times-reading Yankee, led to some sardonic eye-rolling and at least one memorable song in response; yet this does nothing to mitigate the rawness of Young’s vision or the authenticity of his outrage. — Dan Wiencek

69. ”Bring ‘Em Home” – Pete Seeger/Bruce Springsteen. Issue: War

Imperialism has human consequences — it takes our sons and daughters, kills a bunch of them, and returns many of the rest damaged for the things they’ve seen and done. Enough is enough. Let the leaders in suits and their uniformed generals fight it out amongst themselves. Rent a coliseum or a back alley. Give them guns or stones or their bare fists. Return our children to us; let us do the work required to help them heal. — Rob Smith

68. ”Radio Radio” – Elvis Costello. Issue: Music industry

He wants to bite the hand that feeds him; he wants to bite that hand so badly. Elvis Costello’s rant against the music industry is notable for its tuneful ferocity, but also for its core contradiction. He does want to bite, but let’s be clear — he expects to be fed too. As rabidly as he attacks radio and the self-satisfied pageantry of mainstream rock in the late seventies, he cannot disguise his blatant thirst for recognition. There’s no revenge or guilt here, just a cocky young punk giving the middle finger with one hand and reaching for an audience with the other. — Matt Springer

67. ”Superstition” – Stevie Wonder. Issue: Superstition

Is this a protest song? I dunno. But it’s mighty fine! Sometimes, people stay in one place because they think they are supposed to. They think that Bad Things will happen if they try to make their lives better. Stevie Wonder told them that this wasn’t the way. And you can dance to it. — Ann Logue

66. ”Everybody Wants to Rule the World” – Tears for Fears. Issue: Abuse of power

Back then, it was about Gorbachev, Reagan and Gaddafi, greed on Wall Street, and yuppie scum like Donald Trump. Today it rings true about Putin, Cheney, Ailes and (stifles the emerging vomit) our new president. Even global warming was on their radar as Curt Smith sang ”You acting on your best behavior, turn your back on Mother Nature.” — Keith Creighton

65. ”Party At Ground Zero” – Fishbone. Issue: Nuclear war

Similar territory to “1999” here, but it’s an even bigger party at the nuclear apocalypse here, thanks to Fishbone’s merry mix of ska, funk, rock and irreverent lyrics. The horn blasts and walking bass bring to mind a New Orleans jazz funeral, perhaps the best way to go out after the final conflict between those Commies and the Yankee imperialists who’ve come to play. — Beau Dure

64. ”Free Your Mind” – En Vogue. Issue: Prejudice

Want to shatter racist and sexist stereotypes? Start a song with a shoutout to an In Living Color recurring character (”Wrote a song about it!”), then crank up the guitar while throwing those stereotypes back in the haters’ faces. This is not a wispy coffeehouse tune about injustice; it’s a full-throated call of empowerment. — Beau Dure

63. ”Real Men” – Joe Jackson. Issue: Sexism

All these years later, the true meaning of this song is still widely debated. Was it protesting homophobia? Was it Jackson’s coming out song? Did it come out 30 years before the Transgender Tipping Point? Yes. No. All of the above and more. The third single from Jackson’s smash Night and Day album was a call for all of us to explore, dismantle and reinvent gender norms more relevant and urgent today than ever. — Keith Creighton

62. ”Fast Car” – Tracy Chapman. Issue: Poverty

The whole of youth music — in whatever form it arrives as — is preoccupied by escape. Escape from suburbia’s stagnation, from the clutches of the ghetto, from that overbearing girlfriend/boyfriend, from hopelessness, from heroin, from just about anything you can imagine. Bruce Springsteen built his early years around the yearning for release from a life seemed set for you before you were even born. In some strange way I am reminded of Springsteen when I hear Tracy Chapman. It has nothing to do with the deep timbre of her voice, but of that same tiny spark in the soul. That one that is dying to escape, even if it is only for a little while, only temporary, and reversed with the flick of the gearshift. The car that promises to get her away from the place she’s at is also attached to someone that will likely bring just as much misery with them as they’re attempting to drive away from. In that, the song is laden with tragedy and, I suspect, if Bruce has heard the song before (I imagine he has), he has given it the mental nod of kinship. — Dw. Dunphy

61. ”Fuck tha Police” – N.W.A. Issues: Police brutality, racial profiling

Listen, despite being a hip-hop fan from early on, my suburban white kid ass was not ready for “Fuck tha Police.” I was as “woke” as my surroundings allowed, but N.W.A. took things to another level. Knowing controversy elicits attention, this could have been viewed as a stunt, but the delivery is such that the clear protest of racial profiling and police brutality is palatable, even if you’ve never encountered it yourself. — Michael Parr

60. ”I Ain’t Marching Anymore” – Phil Ochs. Issue: War

Phil Ochs is a tough nut to crack. Regarded in his lifetime as a songwriter’s songwriter, revered by the folk scenesters, he never quite broke through to a huge audience the way some of his peers did. Maybe that’s down to the unpolished honk of his voice, or to his uncompromising politics; or maybe the relentless topicality of his work (he likened himself to ”a singing newspaper”) gave many of his songs a built-in expiration date. But when he broadened his scope — as with this indictment of the soldier’s dilemma, past, present, and future — Phil Ochs showed he could write a song for the ages. — Jack Feerick

59. ”Invisible Sun” – The Police. Issues: War, Irish Troubles

The lyrics speak of living under the thumb of a quietly malevolent force. The music is equally bleak, pulsed by a low-end synth; the vocal quiet, almost conspiratorial; the guitar blanketed in the mix but still raging, angered but tamped down, lest the soldiers outside hear it. — Rob Smith

58. ”The Way It Is” – Bruce Hornsby. Issues: Poverty, inequality

Not so much protest insomuch as Civil Rights documentary, “The Way it Is” gave the children of the ’80s something to think about — provided they listened further than its inescapable hook. There is a phrase in the third verse that has come to mind more, of late: “Well, they passed a law in ’64, to give those who ain’t got, a little more, but it only goes so far, ’cause the law don’t change another’s mind.” Given our current state of affairs, I’d say no truer words have been spoken. — Michael Parr

57. ”Pastime Paradise” – Stevie Wonder. Issue: Political apathy

After being inspired by Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise,” which itself was a cover of Weird Al’s “Amish Paradise,” Stevie Wonder invented time travel and returned to 1976 to tack his version onto the masterpiece Songs in the Key of Life. In Wonder’s world, people are so focused on the paradise of the past (perhaps the Dawn of Christ or even the dawn of “Make America Great Again”) or focused on the paradise of the future (including eternal paradise) that they refuse to live in the now. It might also be seen as an indictment on pastimes (hobbies) which is ironic since writing pieces like this for Popdose is my favorite pastime. — Keith Creighton

56. ”911 Is a Joke” – Public Enemy. Issues: Racism, police brutality

The joke in Chicago has long been that the cops are so bad here, even the white people are afraid of them. Ha ha. On January 13, 2017, the U.S. Justice Department filed charges that were not exactly newsworthy: the Chicago Police Department is alleged to have a history of excessive force and racist behavior. Public Enemy told us as much in 1990, but they were rappers, so only white teenagers paid any attention. — Ann Logue

55. ”Mississippi Goddam” – Nina Simone. Issue: Racism

”The name of this tune is Mississippi Goddam,’” says Nina Simone at the start of this song, recorded live at Carnegie Hall, ”and I mean every word of it.” In a time when black activism was roughly divided between the inclusive, nonviolent protests of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the one hand and the by-any-means-necessary urgency of Malcolm X on the other, Nina Simone firmly identified with the latter. (She lived next door to Malcolm for a time, and supposedly once told King, ”I am not non-violent!”) Appropriately, ”Mississippi Goddam” gives exactly no quarter in demanding all the rights and privileges black Americans had been denied, and fuck you if it makes you uncomfortable. (The song’s lone feint at accommodation is a beautifully pointed insult: “You don’t have to live next to me/Just give me my equality!”) Today, when a black football player can’t even take a knee without white people losing their shit, Simone’s anger at white insistence that she ”do it slow” is just as relevant today as in 1964, and just as necessary. — Dan Wiencek

54. ”The Dead Heart” – Midnight Oil. Issue: Treatment of indigenous peoples

Diesel and Dust is Midnight Oil’s masterpiece, a collection of protest songs that are most pointedly about their native Australia’s treatment of indigenous people but still resonate elsewhere. With stark arrangements evocative of wide-open spaces being corrupted by capitalist greed, future lawmaker Peter Garrett issues stern words reminding us that the white man has made a habit of taking and breaking promises. And the lyric ”collected companies got more right than people” was just a little ahead of its time. — Beau Dure

53. ”And the Band Played ‘Waltzing Matilda'” – Eric Bogle. Issue: War

Perhaps the finest anti-war song ever written, ”And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda’” works by making the personal universal. In unhurried, plainspoken language, Bogle takes five verses to tell the story of an Australian vagabond drafted to fight in World War I, and his appointment with destiny during the grinding eight-month siege at Gallipoli, where ANZAC forces under British command were used as cannon fodder. The larger geopolitical ramifications aren’t the song’s concern, though; it confines itself to the viewpoint of a single man, damaged by a war he never understood and never truly cared about — one man who speaks for every veteran, everyone who’s ever been swept up in events bigger than themselves. A million deaths is a statistic; a single death — or a single life — is a tragedy. Covered many times; for my money, the best version is by the Pogues. — Jack Feerick

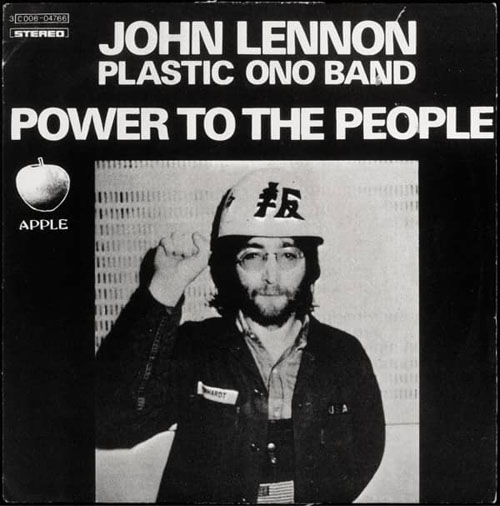

52. ”Power to the People” – John Lennon. Issues: Injustice, revolution, sexism

In the 1970s, Lennon was cranking out protest songs as fast as someone with a new Sharpee and lots of cardboard and sticks. What good is a protest if people don’t have anything to sing? Here are some fun facts about it: it was credited to the Plastic Ono Band, which at the time included Klaus Voormann (who went onto form Trio, the band of “Da Da Da” fame) and Alan White who makes the Rock Hall this year when Yes is inducted. Also, if you Google lyrics for the song, Google Play credits it to the Black Eyed Peas — where can I protest that??? — Keith Creighton

51. ”Big Yellow Taxi” – Joni Mitchell. Issue: Environmental degradation

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot, with a pink hotel, a boutique and a swinging hotspot.” Joni Mitchell wrote the song about a trip to Hawaii but, like The Pretenders’ “My City Was Gone,” it applies to just about everywhere. Loads of people have covered it over the years, changing the lyrics to fit the times or their gender, including Mitchell. — Keith Creighton

50. ”Man in Black” – Johnny Cash. Issues: Injustice, inequality, Vietnam War

In which Johnny Cash, still known for being a wildman, a speed freak, a clown, writes a song about a character — a mournful, prophetic figure, a somber sin-eater who bears the darkness of this fallen world like a crown of thorns. And as the years pass he is consumed by his own creation, the gravitas of the character bleeding into the person of Cash himself — until, when Death finally comes for him, he seems more monument than man. It’s the greatest piece of mythmaking in American pop. — Jack Feerick

49. ”The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” – Bob Dylan. Issue: Injustice

Though not as pointed and venomous as ”Masters of War,” ”The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” arguably represents the pinnacle of Dylan’s ”protest singer” phase. The song confidently deploys both sledgehammer bluntness — if William Zantzinger had had a moustache, you can bet he’d have twirled it — and astonishing subtlety: most listeners catch on that Hattie Carroll is black and William Zantzinger white even though the song never explicitly says so, and Hattie Carroll’s death, tragic as it is, is ultimately not what the singer is protesting. It’s the failure of the system — ”the ladder of law” that should have ”no top and no bottom” — that finally inspires our tears. — Dan Wiencek

48. ”Waiting for the Great Leap Forward” – Billy Bragg. Issues: Capitalism, political activism

The scene couldn’t be more relevant. The Left, embittered and demoralized after a humiliating general election defeat, briefly wonders whether there’s a point to all this — then squares its collective shoulders and gets back to the real work of societal change: distributing pamphlets, organizing bake sales, raising money, running lectures, recruiting, campaigning. We all want to think that the revolution will come in one enormous spasm, a clean break with our benighted past that ushers in a glorious future. And you can hold out for that, if you want; but don’t hold your breath. And there are plenty of constructive ways to keep busy in the meantime. — Jack Feerick

47. ”I Am Woman” – Helen Reddy. Issue: Sexism

I was watching an episode of an old game show recently, dating from back in the early 1970s. The mood on the stage was jovial and in good humor, but that was by the standards of the day. It was hard to watch the male stars, who comprised part of the celebrity guest panel, leer at the female stars and throw out barely concealed come-ons to them. This was, of course, a network-funded gameshow and so a sense of that “ol’ boy” demeanor, that “take a spin around, honey, so I can get a REAL GOOD LOOK at ya” attitude was institutionalized. But roughly around the same time, Helen Reddy released this song. To be honest, the song is a blunt instrument and painfully earnest. No wonder it became a bit of a punchline later in the decade, but there in the early seventies, the song almost had to be. It had to say, “We’re not going anywhere, we’re not accepting second best, and we’re not taking any crap from you” in the most direct manner possible. “I Am Woman” may not be one of the songs on this list that had a vibrant afterlife decades later, but it got the job done and accepted no quarter. — Dw. Dunphy

46. ”99 Luftballons” – Nena. Issue: Nuclear war

A nursery rhyme for the nuclear age, “99 Luftballons” is a wonderfully playful song about an absurd situation that came a bit too close to happening a few times in the Cold War. Nena’s sweet delivery captures the innocence of the harmless balloons that trigger World War III, and she even sounds a hopeful note of resilience from the ashes in the final verse. — Beau Dure

45. ”White People for Peace” – Against Me! Issue: Protest songs

It’s one thing to march on Washington or stand down a tank in Tiananmen Square, it’s another to play hippie for a weekend singing John Lennon songs at your local campus quad. Do you think Putin ever said, ”Well, I really want to annex Crimea but I don’t want to upset those hottie bohos at Oberlin”? ”White People For Peace” was the blistering highlight of Against Me’s New Wave, for me the best rock album of the past 20 years. — Keith Creighton

44. ”American Skin (41 Shots)” – Bruce Springsteen. Issue: Shooting of Amadou Diallo

A black youth stands in front of thousands of white men, arms aloft, a position of fear and submission at the same time. A few feet away, Jake Clemons’ lead singer, Bruce Springsteen, intones the opening words of his achingly powerful song for Amadou Diallo, “American Skin (41 Shots).” It’s 2016, and the song is fifteen years old; it is more relevant than it has ever been, an elegy for yesterday, today and a sad tomorrow. Springsteen’s great gift is to inhabit characters beyond his own experience and cut to the quick with lacerating detail; with Clemons at his side, silent and deafening, the deadly imagery never felt more real, or more devastating. In the waning days of last year’s presidential election, Mary J. Blige brought the full weight of her musical power to the song as part of an interview with Hillary Clinton; like so much great protest music, to sing it well is to own it. — Matt Springer

43. ”Sisters Are Doing It for Themselves” – Eurythmics with Aretha Franklin. Issue: Sexism

People talk a lot about the sexism in the 2016 presidental election. The best example is the comparison between Donald Trump and Carleton Fiorina. Neither was remotely qualified to be president. Both were running on their business expertise despite track records that were appalling. Both allowed vanity to trick them into bizarre looks (bad combover for him, too much plastic surgery for her). Fiorina lost, which was appropriate. For some reason, though, Trump got voters. Go figure. We’re all trying to figure that out. As long as a penis allows one to overcome mediocrity, we won’t have true equality. In the meantime, we have Aretha, who has no peer. And that’s a good thing. — Ann Logue

42. ”Everyday People” – Sly and The Family Stone. Issue: Racism

So maybe — just maybe — I chose this song for reasons other than the message it carries. Oh, I dutifully took on the message when I finally was able to understand it, but upon its release in 1969 I wouldn’t have even been a year old yet. And still, I had this 45 RPM record in my playpen in the duplex in Long Branch, New Jersey. I remember that canary yellow Epic Records label, and I remember spinning it on my toe because — hello — I was a baby and babies don’t have record players. So you can say I and this song grew up together. It was always a friend, right down to the “scoobie-doobie-doobies,” but as I got a little older, I also took that message with me. Like a carrier of a virus, but a good virus, if that makes sense. “We gotta live together.” That’s not wishful thinking. That’s a guide to survival. Everyday people, from everywhere in the world, carry a piece of the puzzle. If we don’t work together, we don’t put the puzzle together, instead leaving gaping holes where understanding ought to be. We’d better accept those who don’t look, act, or speak like us. All of us are depending on it. — Dw. Dunphy

41. ”If I Had a Rocket Launcher” – Bruce Cockburn. Issue: War in Central America

Canadian troubadour Bruce Cockburn started his career in 1970, and has been travelling the world and writing about what he sees from the very start. His folk-inflected early work was mournful and finely crafted. But with ”Rocket Launcher” — inspired by an Oxfam-sponsored visit to refugee camps along the Mexico/Guatemala border — Cockburn abandoned elegance, speaking instead from a place of raw, helpless anguish. It’s a powerful, troubling song, all the more so for its refusal to pass judgment on the anger of the oppressed. Violence is never the answer, of course. But man, what if it was you who had that rocket launcher? — Jack Feerick

40. ”Revolution” – The Beatles. Issue: Political extremism

”Revolution” is a paradox: one of the Beatles’ most driving, fiery performances delivering the reassurance that ”you know it’s gonna be alright.” The radical left were disgusted with what they saw as Lennon’s privileged, rich-man’s complacency (Nina Simone went so far as to write a song in response claiming that the Constitution was “gonna have to bend”), and it was partly to earn back their good graces that he wrote the much more strident ”Power to the People” three years later. Yet with its appeals to moderation in highly polarized times, ”Revolution” is an extraordinarily brave statement, and a far more genuine reflection of Lennon’s optimistic worldview. — Dan Wiencek

39. ”Rain on the Scarecrow” – John Mellencamp. Issue: Farm relief

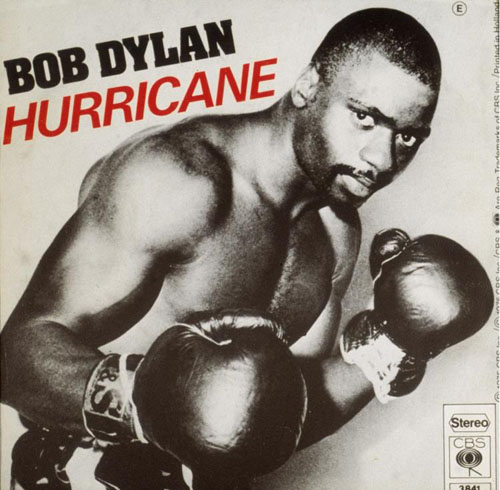

We already knew that John Mellencamp was an angry young man, but the plight of American farmers in the 1980s really got under his skin and fed into the rage he poured into this song. Drawing from what he was seeing in his home state of Indiana and across the U.S., Mellencamp became the voice of the men and women who had helped feed this country, but were now losing their land to banks and corporations. From the opening chime of Larry Crane and Mike Wachnic’s guitars. to Kenny Aronoff’s thundering drums, ”Rain on the Scarecrow” is a call to arms and one of Mellencamp’s most pointed looks at the treatment of the common man. It’s obvious that Ol’ JCM is pissed off, and if you aren’t by the end of this song there’s something wrong with you. — Scott Malchus

38. ”Hurricane” – Bob Dylan. Issue: Injustice

One of the few songs Dylan co-wrote with another songwriter (in this case Jacques Levy), ”Hurricane” tells the true tale of Rubin ”Hurricane” Carter, a middleweight fighter wrongly convicted of murder in 1966. After reading Carter’s 1975 autobiography and meeting him in person, Dylan felt he had to do something to help Carter. ”Hurricane” is an eight-minute epic free of Dylan’s obtuse poetry, a straightforward retelling of the crime that shows a black man being railroaded by a corrupt legal system. Say what you will about artists keeping their mouths shut about political causes, here’s an example of a SONG actually helping a man gain his freedom. In 1985, Carter’s conviction was overturned. It certainly wasn’t all because of Dylan, but it did raise Carter’s profile and bring the attention of his case to the public eye. — Scott Malchus

37. ”God Is a Bullet” – Concrete Blonde. Issue: Gun violence

In 2014, during the terrible summer of Ferguson, I kept coming back to this song. Its kaleidoscopic portrait of gun violence seemed to echo both the tragedy of Mike Brown — boundless potential, cut down young — and the black comedy of the badged-up redneck chickenshit who put him in the ground. And that blistering coda, where the glam chug drops away as Johnette Napolitano spits a litany of victims — ”John Lennon, Dr. King, Harvey Milk — all gone for GODDAM NOTHING” — catches me between fury and tears every time another life is sacrificed so the paranoid fringe can continue to nurse their sick hard-on for the machinery of murder. Have mercy on us, everyone. — Jack Feerick

36. ”Working Class Hero” – John Lennon. Issue: Conformity

John Lennon’s barebones attack on the ruling classes. In a very subtle manner, he also made strides to point out only individuals can change themselves and to not be fooled by one’s idols. As poignant today as it was then. — Rob Ross

35. ”Fight The Power” – The Isley Brothers. Issue: Abuse of power

This 1975 anthem was used to fire up a generation to fight for their rights to lib-party; later on it inspired a Public Enemy track that mobilized a whole new generation and just last year, it figures (fucking 2016) it was used to move units of Nespresso in that George Clooney/Danny DeVito ad. — Keith Creighton

34. ”Legalize It” – Peter Tosh. Issue: Drug prohibition

One nation’s sacrament is another nation’s contraband. One man’s medicine is his government’s instrument of criminality. Nature’s medicament is her interlopers’ moral outrage. This all is absurd, I think, taking a sip of my whiskey. Legalize it. Everywhere. Now. — Rob Smith

33. ”My City Was Gone” – The Pretenders. Issue: Urban development

I grew up in Ohio, not too far from Seneca and Cuyahoga Falls, so Chrissie Hynde’s protest of suburban sprawl wasn’t just a metaphor; it was real life. Every time I returned home from Chicago to see my parents, more and more farmland gave way to now vacant strip malls and chain restaurants. Decades later, this b-side to Brass in Pocket’ remains one of Hynde’s most essential songs. — Keith Creighton

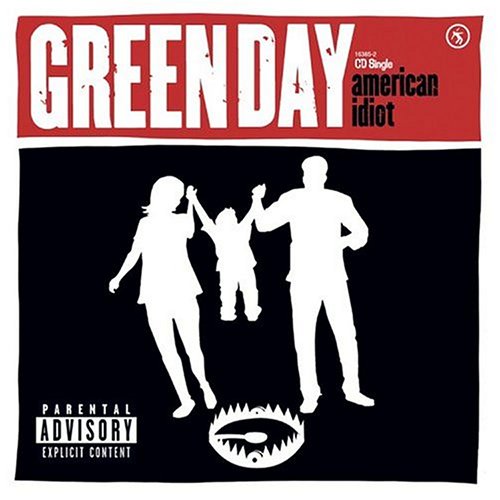

32. ”American Idiot” – Green Day. Issues: Ignorance, propaganda

Green Day played raucous gigs on Gilman Street and released punky albums on Lookout! Records prior to their ka-jillion selling smash, Dookie, but the most punk thing they ever did was the magnum opus rock opera calling out anti-intellectual, Fox News-addicted, hypocritical, ignorant, race-baiting White America on their bullshit. — Keith Creighton

31. ”Who’ll Stop the Rain” – Creedence Clearwater Revival. Issues: War, injustice

Stately, bittersweet folk rock from one of the era’s masters, “Who’ll Stop The Rain” abstracts the specifics of the 1960s within a powerful metaphor. It’s buttressed by some of John Fogerty’s most beautiful and evocative lyrics — “clouds of mystery” and “caught up in the fable” are turns of phrase worthy of Dylan, whose “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” had to have inspired this song’s metaphor. — Matt Springer

30. ”Masters of War” – Bob Dylan. Issue: Military-industrial complex

The politics undergirding Bob Dylan’s early songs are often much more subtle than they’re given credit for — see ”Only a Pawn in Their Game” above, for example — and sometimes they’re as obvious as a rock to the face. In ”Masters of War,” Dylan gets right to the point, calling out the military-industrial complex (Eisenhower had only coined the term a few years previously) for its willingness to imperil the world for profit. The accompaniment is as relentless as the sentiment, with a single, twanging minor chord powering most of the song as Dylan spits the most vitriolic attack he would ever put on vinyl: ”And I hope that you die, and your death’ll come soon/I’ll follow your casket in the pale afternoon/And I’ll watch while you’re lowered down to your deathbed/And I’ll stand o’er your grave ’til I’m sure that you’re dead.” — Dan Wiencek

29. ”My Generation” – The Who. Issue: Generation gap

Townshend’s statement was the ultimate clarion call for the burgeoning youthquake around the world; the stutter is the perfect emphasis on the inarticulation and frustration of young people that has transcended the decades. And you’ll never hear another head-turning bass solo like the one delivered by Entwistle again. — Rob Ross

28. ”Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” – Marvin Gaye. Issues: Poverty, prejudice

27. ”Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” – Marvin Gaye. Issue: Pollution

What a whiplash “Mercy Mercy Me” might have caused listeners back in the day. Here was Motown’s number-one soul man, Marvin Gaye, not only preaching against the poor stewardship of the human race, but presenting it on a record with no shortage of pointed and poignant commentary, 1971’s What’s Going On. And in a way, it’s an album and a song only Marvin could have done. Other people might have gone at the subject harder, been more pointed, more combative. It was Marvin’s croon that made such a weird and difficult subject not only palatable, but hummable. Applying the loverman touch to concepts that could have come off as either hippy-dippy or nerdish got the song, and the ideas, into the listener’s head. That idea is, “You’ve been given a gift. You are using that gift unwisely. One day, it will go, and nothing you can do will bring that back, no matter how hard you wish for it.” Personal responsibility never sounded so smooth.

Gaye was not finished. Having looked at the sky and the water and the ground with clear, sad eyes, he then trained them on another heartbreak: home. Or rather, the home so many African-Americans, minorities and poor whites were experiencing, but black people most especially. And even though it is called “Inner City Blues,” that’s merely the trappings (in every sense of the word). When Gaye sings, “Makes me wanna holler, the way they do my life, ’cause this ain’t living,” that’s a generational voice. That’s the inner city on a map and the inner city of the soul. So, okay. To get anywhere in this life, you need trust, nourishment, education, security, a fair shot at advancement, and a way to actually earn your keep in the world. Instead, you’re not trusted because of the way you look. You can’t afford the nourishment of the body or the mind, so you have to get the cheap stuff, filled to overflowing with sugar that’s causing diabetes to ravage across your community. The best teachers either won’t come here to teach “those people,” or they’re trying their damndest in school districts that have already written the kids off. Your home is on the fringe of some very scary scenes. Nobody’s going to give you a chance because you had to work the jobs nobody else wanted just to get by and your education suffered. It’s either that or take up selling and/or using drugs for money. Selling your body. Or taking up the gun, taking what may not be yours, but learning at such a formative age that you’ll never get those things anyway. You’re inferior, not good enough. You deserve this inner city ghetto, at least that’s how it feels anyway. In the end, it’s amazing that What’s Going On became the well-regarded classic it is. We’re still ignoring its accursed equations. — Dw. Dunphy

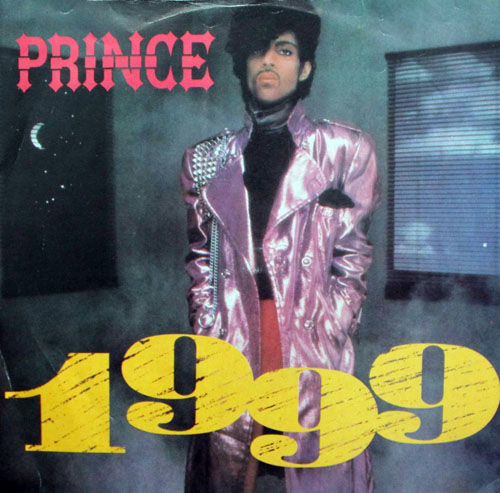

26. ”1999″ – Prince. Issue: Nuclear war

While the radio edit(s) of “1999” never made it to his pitch-shifted “Mommy, why does everybody have a bomb?” refrain, the message of Prince’s master class in delivering social commentary while making asses wiggle is clear: If the governments of the world are in a race to destroy it, why not dance your life away. Throughout his career, until the very end, he served as a voice of dissent, calling for change in the most melodic way possible. — Michael Parr

25. ”Killing in the Name Of” – Rage Against the Machine. Issues: Institutional racism, police brutality

“Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me.” Yeah, that pretty much says it all. — Scott Malchus

24. ”Dear God” – XTC. Issues: Religion

When my parents realized the local pastor was embezzling the church funds on new cars and a posh house while urging parishioners to cough up more dough to fix the church AC, they quit the church and we were damned to hell. Well, until “Dear God” came on MTV and opened my eyes to how religion was created by man to control man. Let’s not forget how entrenched God was, and still is, in popular music, even protest songs. For me, “Dear God” was the dawning of the Age of the Atheist. — Keith Creighton

23. ”Born in the U.S.A.” – Bruce Springsteen. Issues: Vietnam veterans, economic injustice

Like his idol Woody Guthrie’s ”This Land is Your Land,” Springsteen’s rock anthem is still misinterpreted by people who believe it’s a celebration of the American spirit. It’s not. ”Born in the USA” was Springsteen’s cry for the respect due to the soldiers who sacrificed mind, body and soul in Vietnam. His narrator returns from the war to find his country disregards him and his brothers in arms. While he searches for work and mourns the loss of his brother who died in Saigon, the song’s hero reminds us that America is a land for everyone, even the disenfranchised and forgotten. Listen closely to the Boss’ performance, the ferocity in which Max Weinberg attacks the drums and you understand that this is one pissed off song that only grows in power with each listen. Moreover, it resonates as much today as it did in 1984, which is just fucking sad. — Scott Malchus

22. ”Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” – James Brown. Issue: Black pride

The assassination of Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968, sent shockwaves throughout the nation, with riots breaking out in cities ranging from New York and Chicago to Pittsburgh and Detroit. Boston escaped unscathed, and many say it was because James Brown gave a televised concert the next night, a concert where the Hardest Working Man in Show Business pleaded for his audience to maintain their self-respect even in the midst of their grief and anger. It was an amazing testament to the power of popular music in general and the charisma and conscience of James Brown in particular, and Brown cemented his status as one of America’s preeminent black voices later that year with “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Backed by a chorus chiming the song’s title, Brown lays out a case for black empowerment that is relentlessly defiant without ever tipping over into rage. — Dan Wiencek

21. ”Rocking In The Free World” – Neil Young. Issue: George H. W. Bush

A series of body blows to the Bush I administration and its policies, Neil Young’s deafening screed against greed helped contribute to his late-eighties career resurgence. Like Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” before it, the irony of the song’s chorus led to its misuse on plenty of occasions. But when Young screams about that one more kid who will “never get to be cool,” the pain and irony is unmistakable. — Matt Springer

20. ”Beds Are Burning” – Midnight Oil. Issue: Native displacement

Little known fact: One of Midnight Oil’s biggest hits was about the displacement of native Austrailian Aboriginal people (the Pintupi) and not the theme song to that Farrah Fawcett TV movie about domestic abuse. — Keith Creighton

19. ”Get Up Stand Up” – Bob Marley & the Wailers. Issue: Injustice

This rebellious number from the island of Jamaica was actually inspired by Marley’s time in Haiti. For oppression to be thwarted, man must not accept the oppressor; must not normalize the behavior. While the finger here is pointed at Christianity as the oppressor — Marley, being a Rastafari, saw Christianity as a corruption of the Bible — the message rings true in many applications. — Michael Parr

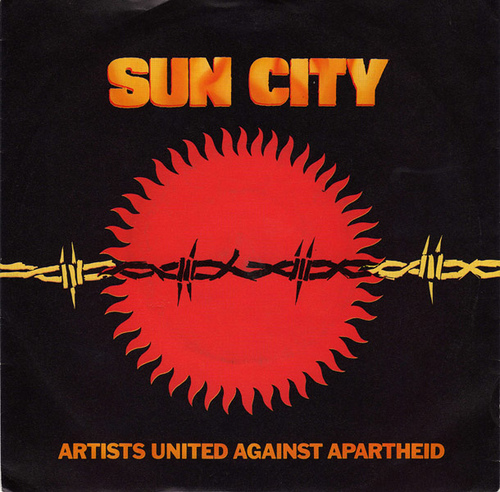

18. ”Sun City” – Artists United Against Apartheid. Issue: Apartheid

Nastier and funkier than most of the ensemble-charity songs of the era, Sun City brings down the walls of apartheid with a powerful blast of diversity. Miles Davis’ trumpet leads us to Run-DMC’s opening rap, Joey Ramone wails about Reagan, Clarence Clemons takes a late sax solo, Darlene Love leaves little doubt about the farce of ”quiet diplomacy,” and Bruce and Bono wring every bit of drama from their lines. It’s a quick education in foreign policy and musical styles, and yet everything fits together perfectly. — Beau Dure

17. ”The Message” – Grandmaster Flash + The Furious Five. Issues: War on Drugs, Reagan era

Like Stevie’s “Living for the City” before it, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” paints a bleakly accurate portrait of life in the inner city. The roots of conscious rap were sewn here, with many trying — and failing — to deliver the truth spoken by Melle Mel, “It’s like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder how I keep from going under.” — Michael Parr

16. ”Won’t Get Fooled Again” – The Who. Issue: Political apathy

Gallons of ink have been spilled debating exactly what revolution is the target of The Who’s doubts here. But keeping it vague works wonders here. Any new boss needs to be greeted with skepticism and accountability, which is why this song will always be timely. — Beau Dure

15. ”Imagine” – John Lennon. Issues: War, greed, poverty

“Aspirational” isn’t the first word that comes to mind when one thinks about protest music. It’s most often employed as a salvo against injustice. John Lennon’s brilliance with “Imagine” was to approach the ails of the world from the opposite direction — don’t think about what’s wrong; instead, consider what our world can be like if we start doing things right. — Matt Springer

14. ”Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today)” – The Temptations. Issues: War, taxation, societal unrest

Like many children of the 80s, I knew the Love and Rockets cover long before I heard the Temptations’ psychedelic soul masterpiece. If Childish Gambino covered it today, you’d be hard pressed to convince Millennials it wasn’t written about the events of 2016. — Keith Creighton

13. ”Living for the City” – Stevie Wonder. Issues: Prejudice, injustice

The thing about ”Living for the City” is that — strictly on a musical level — it shouldn’t work at all. The verse is a single-chord groove into a perfunctory IV-V chorus, then the falling, counterintuitive chords of the bridge — and then he puts a skit right in the middle of the damned song, where you can’t skip it. But the song is a marvel, both in its constituent parts — the chunky stroll of the verse is one of the greatest drum performances in a career filled with them, the jazzy line of the bridge one of the most indelible melodies — and in its construction; even the cornpone elements of the skit (”Tall buildin’s an’ ever’thang!”) set up the contrast for the explosive finish. This is Stevie at the height of his powers, alchemizing musical gold from the pain and degradation of the Black experience. — Jack Feerick

12. ”We Shall Overcome” – Pete Seeger. Issue: Civil rights

What is a “protest song,” anyway? In its rawest state, I suppose any song with an opinion and some sense of advocacy in its regard could be deemed a protest song and would not be inaccurate. Yet, when people imagine what a protest song is, they’ll likely hear something such as “We Shall Overcome.” Although frequently credited solely to Pete Seeger — and with good reaon as it became somewhat a trademark of his — its first incarnation lyrically arrived in 1900 as a hymn. The record states that a version that is closer to our current understanding of the song arrived in 1947 during, as you might presume, a protest. Through Seeger it became one of a handful of songs that defined the African-American civil rights movement. Even today it says in a firm voice, “We will persevere, we will not waver,” in mantra-like phrases. “We shall overcome … we’ll walk hand in hand … we are not afraid.” The fact that it perfectly inhabits the gospel/folk idiom means that even without that one lone acoustic guitar, a few voices in unison can sing this simple song and carry a complex sentiment along with it. — Dw. Dunphy

11. ”A Change is Gonna Come” – Sam Cooke. Issue: Racism

Born out of a lifetime’s worth of indignities foisted upon black Americans, rife with equal parts pain and hope, sung by a man who straddled the spiritual and secular as few before or after him. In the mid- and late Sixties, it was arguably THE anthem for a generation in the midst of struggle, and it resonates across the years to today’s struggles, as few songs (or books or speeches or films) can. ”It’s been a long time comin’,” yes, and yet there still seems so much longer to go. — Rob Smith

10. ”For What It’s Worth” – Buffalo Springfield. Issue: Civil disobedience

A view of the L.A. Sunset Strip riots, this track has gained a much greater, universal meaning in the 50 years since its release. Timely and timeless, it says quite pointedly what many people thought then and are (not surprisingly) thinking now. In the broader stroke, it may be even more chilling in the modern context. — Rob Ross

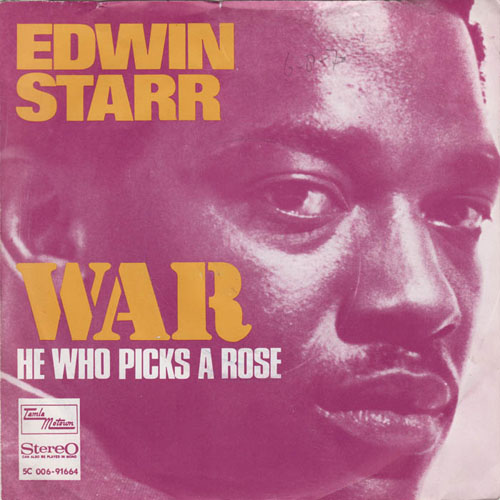

9. ”War” – Edwin Starr. Issue: War

Equal measures protest chant and barn-burning groove, few tunes rallied the counterculture like Edwin Starr’s “War.” I guarantee that should you mimic Starr’s guttural shout of “WAR! HUH!” in a crowded room that someone in that room is going to come back at you with a “Good God, y’all.” Powerful in its simplicity, it stands as one of the most effective protest songs of its — or any — time. — Michael Parr

8. ”What’s Going On” – Marvin Gaye. Issue: Generational conflict

The son of a preacher pleads for peace, love and understanding, as strings and percussion and stray voices swirl all around him. His arguments seem naÁ¯ve (”War is not the answer/For only love can conquer hate”) when compared to the damage being done by billy clubs in the streets, by officials in state and federal governments, and by opposing soldiers in jungles half a world away. Yet those arguments are delivered with strength, if not authority, emanating from an imperative, the thought of what could happen if the sides couldn’t talk, or were unwilling to listen. ”Tell me what’s going on,” he sings, ”I’ll tell you what’s going on.” I’ll hear you out, then you hear me out, and maybe we’ll find common ground. God help us if we don’t even try. — Rob Smith

7. ”Fight The Power” – Public Enemy. Issue: Abuse of power

Culling references from many of the songs that precede it on this very list, Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” aims to educate and motivate a new generation of listeners without an anthem of their own. Chuck D’s call to arms didn’t fall on deaf ears; rather it radicalized a entire generation of hip-hop artists (and fans) to fight systemic bias and institutional racism with actions and words. — Michael Parr

6. ”Give Peace a Chance” – John Lennon. Issue: War

Sometimes it only takes a simple melody and a great chorus to get across the message. John Lennon raps a series of verses that fill in the space until you get to the most important part of the song. ”All we are saying is give peace a chance.” Indeed. — Scott Malchus

5. ”Strange Fruit” – Billie Holiday. Issue: Lynching

Shocking enough when Billie Holiday first recorded it nearly 80 years ago, ”Strange Fruit” remains one of the most disturbing records ever made, an unflinching look at a part of American life — that is to say, the torture and murder of black Americans by white mobs — that most whites either politely tried to ignore or else tacitly approved of, provided they weren’t actually carrying it out. ”Strange Fruit” grabs you by the hair and forces you to take in every grisly detail: the bulging eyes, the twisted mouth, the crows picking at what remains of the strange and bitter crop. The fact that a song like “Strange Fruit” had to be written in what purports to be the land of liberty and equality is a disgrace; the fact that a work of such honesty and courage exists at all, let alone still survives today with its power undiminished, is a small miracle. There’s nothing else like it in American music, and given the song’s peculiar circumstances, we probably should be grateful for that. — Dan Wiencek

4. ”Ohio” – Crosby Stills Nash and Young. Issue: Vietnam War

Inspired by the Kent State shooting by the Ohio National Guard on May 4, 1970, Neil Young wrote ”Ohio” quickly. Three weeks after the tragedy, he called together his bandmates Crosby, Stills and Nash to record one of the most pointed attacks on Nixon politics and the unrest in the country at the time. ”Ohio” was pressed and released just weeks later, which may not sound like a big feat in our era, but in the early days of rock n roll was quite an accomplishment. The urgency to get the music out is heard throughout the record. Their blood is boiling and their emotions are wrought. Those fallen students weren’t just their fans, they were peers. The dead could have been them. That fear and anger feeds the song, especially Crosby’s pleas of ”Why?” during the ”Ohio’s” fade out. — Scott Malchus

3. ”Biko” – Peter Gabriel. Issue: Apartheid

Many years before rock stars demanded they ain’t gonna play Sun City, Peter Gabriel, late of Genesis, ended his most confrontational and disturbing album yet, the third and otherwise-known “melt” album, with a straightforward track. Look into the dark center of police room 619 where South African activist Stephen Biko was brought. Imagine the blows that rained on him during that “interrogation,” captured in the gutteral “Hoooh!!” uttered by Gabriel’s guest singers. No, at this time, pop culture was not paying attention to apartheid, so there’s every possibility that the message being put across was going over peoples’ heads. It was instead, in my belief, laying the groundwork. Gabriel was performing an act of dark journalism, disguised as a mood piece. In my mind’s eye I expected people cracking open that album in 1980, taking in all of its songs, and going away with that last, haunted tune. It was a form of preparation. See what’s coming. Be ready for it. You can’t say you didn’t know anymore. — Dw. Dunphy

2. ”Sunday Bloody Sunday” – U2. Issue: Irish Troubles

The early years of MTV were all about marrying hit songs with unforgettable images — none more dramatic than Bono waving that flag in front of the masses while singing ”How Long, How Long Must We Sing This Song?” during the definitive live version of the War album track. While the song was about Northern Ireland and the crowd was from suburban Denver, it was still one of the most iconic moments in the history of rock and roll. — Keith Creighton

1. ”Fortunate Son” – Creedence Clearwater Revival. Issues: The draft, economic inequality

Vietnam certainly wasn’t the first war in which privileged people coerced the less-privileged classes to man the front lines. But the new medium of television helped the country see exactly what we were drafting for, and John Fogerty effectively distilled that anger to a series of dead-on zingers about who was pulling the strings and whose strings were being pulled. And who would have guessed that 45 years later, we’d still be electing fortunate sons? — Beau Dure

And speaking of fortunate sons …

Bonus: ”Fergus Laing” – Richard Thompson. Issue: Crass, egomaniacal property developers with short fingers and/or penises

As America’s 45th president pauses from his endless Twitter feuds long enough to assume the reins of power, our country’s future seems especially uncertain. Who is to say what a list like this might look like in four years (or, god help us, eight)? All we can predict is that as the new president acts, so will the world’s committed, conscientious artists step in to serve as our voice. Until that happens, let Richard Thompson’s words act as reminder of the true measure of our next Commander in Chief:

Fergus Laing, he builds and builds

But small is his erection

Fergus Laing has a fine head of hair

When the wind’s in the right direction …

Spotify users can hear these songs by listening to our Greatest Protest Songs of All Time playlist.

Comments