Nicole Atkins is not really interested in interviews as such. Like her music, she lights up when the experience is authentic. Let’s have a conversation instead of the usual topics where the subject has to answer the same five questions, ad infinitum, ad nauseum.

Nicole Atkins is not really interested in interviews as such. Like her music, she lights up when the experience is authentic. Let’s have a conversation instead of the usual topics where the subject has to answer the same five questions, ad infinitum, ad nauseum.

That’s what makes Atkins’ music so engaging right off the bat. She lets you into her process but she’s not going to parse things out in byte-sized Tweets. If you ask for her story, she’ll give it to you, but in a way that, perhaps, you weren’t expecting. In short, if you came to this place for a handful of hooks without anything of consequence to hang them on, you came to the wrong place.

Popdose had an opportunity to catch up with Atkins while she prepared to take the new music on the road. We discussed how the album came to be, the allusions found in the first single, “Vultures” and the accompanying video, and more.

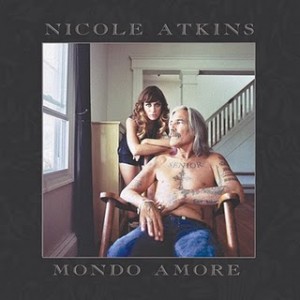

The brand new album is called Mondo Amore, but from everything I’ve read regarding what went on between Neptune City (Atkins’ prior release) and Mondo Amore, it hardly sounds like “the world of love” so, could you lay out what occurred in between?

You know, I was breaking up with my band (The Sea), breaking up with my boyfriend, and breaking up with my label kind of all at the same time while I was writing this. So I actually found it kind of fitting to call it Mondo Amore, mostly because those were three things that I really loved.

That was going on and I was figuring out how to get myself out of that situation. You know, was I just going to sit in New Jersey and feel sorry for myself, go back to school and learn a trade? I called up a few of my old friends from New York and got myself back up there, and just dove into making music again, as my way of getting over everything.

Was that one of the primary reasons for getting out of Asbury Park (New Jersey, which is adjacent to her hometown of Neptune City, of which Shark River Bay runs alongside. This will be an important point later on) and moving back to Brooklyn?

Yeah. You know, I love Asbury Park, it’s where I’m from. But it’s a pretty small town, and when you’re going through a major personal shift, it’s nice to be able to go somewhere that’s a little bigger, to spread out a little bit, and go find yourself again.

You were in Brooklyn prior to that for awhile, so you have a lot of people there who could be a support system whereas, maybe, the people in Asbury Park were prior to your recording and such. They relate from a different frame of reference in terms of how they know you.

It was also because Brooklyn was the place where I was when I was first writing Neptune City and making my first demos. It’s always been a good creative reference point for me being here.

I read in some materials that you were technically still with Columbia Records when you were writing songs that are on Mondo Amore, and that they weren’t coming across to whomever was there, and you were able to get out of your contract. Were you surprised by that reaction from the label, or was it something you understood?

It was just a fucked up situation. The woman I was working with, she wasn’t who I signed on to work with anyway, and as far as music went, her and I just spoke two different languages. So in a way, I wasn’t surprised. She was more like, “Oh, you’re having troubles with your boyfriend, so you should write some angry songs like Alanis Morissette or some shit. That’s the last thing I want to do!

There’s a lot to be said for subtlety and nuance when writing about matters of the heart.

Have you ever had a situation where you were writing something that was just too personal, and you put it away thinking, I can’t put this out there. It’s too far.

Have you ever had a situation where you were writing something that was just too personal, and you put it away thinking, I can’t put this out there. It’s too far.

It all depends. I think there are a few things on this record that could be considered a little too far, but it all depends on how you say them. There’s a lot of ways that you can play with words to, you know, protect your life.

Yeah, there are ways of putting a point across that aren’t blunt and blatant and you can still say what you’re saying, but you’re not going at it with brickbats.

Yeah, and my point of view is that, if it’s not attacking or hurtful, then why not? Go for it. And this is a very personal record and a very emotional record, but also, I feel like it does go out of its way to not point fingers at other people. I’m pointing at myself just as much.

Do you find there’s a lot of that though; not to point fingers at the music that’s out there, but is it too easy to just come out with an angry, “you’ve done me wrong” kind of thing, and does that get snapped up too much?

Oh, yeah. I think so many, especially with popular music, they do that. And it’s like, “ooh, look at how sassy I can be, singing about how this boy screwed me over and he’s a jerk!” You know what? Write in your diary about that shit. It’s tasteless and it’s immature.

This record was a very essential part of me growing up in a way.

How has the relationship with Razor &Tie (the new label) been?

Wonderful! (With a lilt in the voice) “They accept me for who I am!”

They were really, really supportive and they picked up my record as is, and even the artwork, as is. They just made a point of letting me know all the time how much they love it. And that kind of feedback in turn makes you want to keep writing songs. It’s put me in a good creative spot.

I’d imagine it would be better because it would be more a hands-off approach — we signed you on, we believe in what you do. Now go ahead and do it.

It is hands-off, but it’s also… My A&R woman over there, she’s like a total cheerleader. She’ll be like, “What have you got? Oh, that’s awesome!” On the other hand, you don’t want to be told that everything you do is great, but it’s nice to know that you are appreciated for the work that you’re doing and, even in your own way.

The songs I write, they may not be… They may have been smash hits in 1969 or 1972, but it’s nice just to be able to be the artist I want to be, and not have to worry about humongous bottom-lines.

I’ve gathered from your music, past and present, that you’re not the type to be a trendjacker, that there are styles you tend to work with and expand on that palette, rather than jumping onto whatever sound is getting traction today, say hyper-electro. It seems you have no interest in jumping in on someone else’s sound versus trying to find your own.

Yeah, I don’t really have any interest in doing anything solely because it is popular. The only thing I’m interested in is doing what I think sounds good to me. And even with some electro things that are going on today, I wrote a song the other day that I can’t hear it in any other way than with a kind of an electronic percussion bed, but more in a Tom Waits kind of way.

Yeah, I don’t really have any interest in doing anything solely because it is popular. The only thing I’m interested in is doing what I think sounds good to me. And even with some electro things that are going on today, I wrote a song the other day that I can’t hear it in any other way than with a kind of an electronic percussion bed, but more in a Tom Waits kind of way.

It’s funny because I always say, “Oh, I’ll never do anything electronic,” but this one song… I tailor the sound to be what the song needs. When you hear Mondo Amore, there’s a lot of different styles on each song, but I think of an album as a house, and the songs are rooms, and you’re not going to decorate every room the same in the house.

Well, now you’ve got me interested in hearing a song from you that’s influenced by Tom Waits! (laughs)

Yeah, that’ll be on the next record.

There’s a lot about “Vultures,” both the song and the video, that ties back to you. For instance, your original backing band was called The Sea, which broke up, and now you have a new backing band called the Black Sea. In the song, you have a lyric that goes, “Simply run away, hide behind the sea.” Was that directly meant to be an allusion or did it just come out that way, you looked at it and…

No, it’s pretty literal. You’re one of only people that have mentioned that, so far.

The song is talking about working really hard at your job, or working really hard at your relationships, but no matter how hard you work, until you’re “nothing but dirt and bones,” you can still not get what you wanted out of it. That one line is saying, I can disappear from who I’d like to be because at that point, I was acting in a way that I was a person that I didn’t even like, or didn’t even know. So “simply run away and hide behind the sea” was like, in order to not become that person, I’m going to run away and hide behind my band, start making music so I don’t have to be this other person that’s so caught up in bullshit.

The other thing that is striking is the video, which is pretty indescribable other than to say it’s like a suburban death-march to the sea. People are leaving their homes to go walking to the sea to drown themselves… Which kind of looks to me like it’s Shark River.

Yeah, ’cause it is. (Laughs)

It was shot at Shark River!

Yeah. Well, you can take (the meaning of the visuals) that way, or you can say they’re going to lead themselves into a mass baptism for rebirth. I totally think it’s open to interpretation.

I tend to have a negativist streak, I’m afraid.

Yeah, I can tell!

You’ve also said that your approach to songwriting can be lonely. On this album, you worked with Robert Harrison, from the group Cotton Mather, on two songs. What was it like to work with him?

Amazing! He was always one of my favorite writers, and his lyrics are written like novels while his sound is one of the first modern artists that I’ve heard do psychedelic pop in a really classic but modern way without being throwback. So meeting him was a thrill, at first, and then becoming friends with him and writing with him, he gave himself up to me and lived in my life for awhile, and helped me articulate everything I was feeling. Now him and his family, they’re like family to me.

Do you feel your experience has altered your songwriting process afterward?

Definitely. It was like taking a Masters in Songwriting class, and he definitely helped me out a lot with my lyrics, to go beyond what you might ordinarily say and really, really put down all the cliches and say something truly original.

That can be difficult though, because so many tend to be fixated on the cliches. When they here something articulated in a different way, it can be, at first, jarring but I think it has more impact to get it in an alternate way.

The music I’ve always been into is the stuff that is, you know, different.

If you had the chance to collaborate with others, who would be on your short-list?

If you had the chance to collaborate with others, who would be on your short-list?

Nick Cave. I would like to sing with Ian McCullough (from Echo & The Bunnymen), and Robert Plant.

If you’re talking about Raising Sand, that album got so played out around here. I played it, like, every other day.

That was a good one, but have you heard the new one? Band of Joy?

I haven’t heard it yet but wanted to get it because he’s working with Buddy Miller.

Yeah, Buddy and Julie Miller. It’s awesome, it’s great. You have to get it — I like it better than Raising Sand.

The big interview cliche question then: what are you listening to now?

The two things I’m listening to now are Tame Impala, which is a band from Australia, and a lot of ’90s Jon Spencer Blues Explosion.

You’re going out on tour to promote the album; are you someone who just can’t wait to get out and perform or are you less about that?

Nah, that’s why I do this. I love playing live shows. I love putting on a show, and I also love traveling. I move around a lot, so it basically fulfills my need for both. I just love getting out there and meeting people coming to the shows, and just really crafting a great live show experience with the people I play with. That’s the whole reason I do this.

What’s your approach to setting up what you’re going to play? How do you construct your setlist?

It depends on the room and the venue, really. It really depends on the space. We tend to stick to a skeleton of the way the basic show is going to go, and then fill in certain songs here and there to see what kind of crowd this is going to be.

I like the show to go in an arc, similar to how an album is. You start out on the slow burn, then you bring ’em up, and bring ’em up, then arc it really high and make it exciting, then bring ’em back down again. It’s like a rollercoaster.

You said you gravitate to the late-’60s early-’70’s sort of music, do you feel that when you record or sequence an album or show, that you’re really working in that sort of mindset? In that time when things were put together, they were put together with that emotional arc, or the idea that you have to move from peak to peak in the mindset of “side one” and “side two?”

I don’t really think of it as a ’60s thing though. Definitely everybody did a variation of that back then, but I see it more as quality control.

It seems like a conceptual thing to me, though. Like in the ’90s, it seemed to have been done less.

I think there’s a lot of ’90s records that have that arc as well. The whole indie rock scene… The Pixies records or Pavement records, they’re just as conscious of that, and they hold up just as well as some records from the ’60s.

Speaking of the Pixies, they also had a lot of dramatic tension in it, especially when you’re talking about Black Francis (Frank Black, whatever he’s calling himself these days!) and the dynamics that are in each song.

Well, that’s what it comes down to. It’s all about dynamics and drama. Anything that you put together, you’re going to want to seduce the listener or the reader with that kind of tension and drama. If you don’t have it, it’s just a pancake show. You’re just watching a pancake, and nobody wants to watch a pancake.

Thanks go out to Nicole Atkins for taking the time to speak to us while not only preparing for her album’s rollout tour, but for doing so while she was feeling under the weather. Get well soon, Nicole! The interview would not have happened without the assistance of Ken Weinstein at Big Hassle Media and Elliot Fox at Sneak Attack Media.

For more on Nicole Atkins, visit her website, and you can purchase Mondo Amore![]() and her excellent debut album Neptune City

and her excellent debut album Neptune City![]() from Amazon.com.

from Amazon.com.

Comments