”What a mess,” I tell you when I sit down on the folding chair next to your bed, after Jennifer and Ryan have had their turns, their last few quiet moments with you. It’s Saturday morning, fifteen and a half weeks after you got your diagnosis. You’re going to die today. A couple hours after I’m done talking with you, your rattling breath (like a coffeemaker pushing out the last drops of water, every inhalation and exhalation) will cease, and your shoulders—which you’re working hard right now, trying to push out those breaths—will relax, and you’ll be gone. We’ll all be standing around you when it happens, in the family room, leaning on the rails of the bed the hospice folks lent us. For a few moments, none of us will be sure whether it’s actually happened, but the stillness in you will prove it true. Ryan will gently slide your eyelids down, but the room will remain heavy with your presence; it will hang there and we’ll all feel it. It will be several minutes before any of us are ready to leave your side.

”What a mess,” I tell you when I sit down on the folding chair next to your bed, after Jennifer and Ryan have had their turns, their last few quiet moments with you. It’s Saturday morning, fifteen and a half weeks after you got your diagnosis. You’re going to die today. A couple hours after I’m done talking with you, your rattling breath (like a coffeemaker pushing out the last drops of water, every inhalation and exhalation) will cease, and your shoulders—which you’re working hard right now, trying to push out those breaths—will relax, and you’ll be gone. We’ll all be standing around you when it happens, in the family room, leaning on the rails of the bed the hospice folks lent us. For a few moments, none of us will be sure whether it’s actually happened, but the stillness in you will prove it true. Ryan will gently slide your eyelids down, but the room will remain heavy with your presence; it will hang there and we’ll all feel it. It will be several minutes before any of us are ready to leave your side.

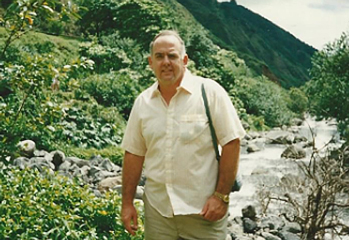

But you’re still here, now, and the first words out of my mouth are, ”What a mess.” It comes out unbidden, without any forethought, though the reason is all around me, is right in front of me. What a mess cancer has made of you. You were a big guy not long ago—six feet tall, hovering around 300 pounds. A lot of ex-athletes get like that; you see them ten or twenty years after they retire, and they resemble the people you recall, the ones you watched play the game (whatever game), but they’re a puffier version. Fifty-plus years ago, you were a star lineman for your high school football team; you wrestled and were on the track and field teams, too, but football was your passion. You told me recently your playing weight the one year you played college ball at Rutgers was 250, which is a tiny lineman by today’s standards. Everyone is bigger and faster.

Cancer has sucked 70 or 80 pounds off you. I can see it in your face; the skin is gray and tight against your cheekbones and forehead, and around your mouth, which has been permanently agape these last couple days, as you try to draw in all the air you can, let it fill in that dry space, force it down into your lungs.

You stare straight up at the ceiling; you’ve been doing that the last two weeks, since Mom and I had to take you back to the ER the last time, since they sent you back to the cancer ward. I don’t know what you’re seeing; up until today you would reach toward it, or make motions with your hands. I’ve wanted so badly to know what is up there, what your motions were controlling or conjuring. Sometimes, you’d say something—”No, Mom, I don’t want to go,” or ”I can hear you, Pop!”—and it made me think you were seeing pieces of your life all over again, memories and visions I would love to share with you, would love to watch with you. When you first started doing this, I’d ask you what you were seeing, but asking only broke the spell. Whatever you’re seeing is a film only you can watch, one that’s obviously reaching its conclusion.

Most of the time, you looked like you were searching, and I blessed whatever force was keeping you fascinated and engaged, perhaps free of pain. Sometimes, you recoiled, throwing up your hands as if you were about to get hit, and I cursed whatever force would frighten or harm you in your vulnerable state.

I hold your hand and I thank you for the things you’ve taught me—about the value of working, the duty of supporting one’s family, of protecting and caring for the things, the people, I love.

I thank you for the experiences you gave me. If I close my eyes, I can see the ocean at Long Beach Island; if I concentrate, I can taste the salt air, and feel the sun on my arms and the back of my neck; I can hear the radio playing Top 40; I can see you sitting in a chair on the deck, or standing at the grill.

I thank you for the experiences you gave me. If I close my eyes, I can see the ocean at Long Beach Island; if I concentrate, I can taste the salt air, and feel the sun on my arms and the back of my neck; I can hear the radio playing Top 40; I can see you sitting in a chair on the deck, or standing at the grill.

If I ever get back to San Francisco, I will find it full with memories, and, most definitely, of tastes and sounds. Yes, you took me to Coit Tower and Golden Gate Park and City Lights Books, but you also bought me clam chowder in a bread bowl at Fisherman’s Wharf; you gave me my first taste of haute cuisine at Tommy Toy’s. We hiked up and down the steep streets, both of us sweating, looking for the Blue Light Bar and Grille, just because Boz Scaggs owned it. You patiently acceded to my wish to drive across the Golden Gate Bridge while playing ”Black Magic Woman,” even though I was pretty sure you hated that song. You took me up to Mill Valley because I’d heard there was a great record store there, and as a result, the two of us spent a couple hours trolling through the vinyl at Village Music. You bought me a copy of Richard ”Groove” Holmes’ Soul Message, because you thought his version of ”Misty” was the very best. You were right.

Even before that trip, you introduced me to jazz by playing me your Wes Montgomery records. The intricacy and beauty of that music—the language of it—confused and fascinated me, and I’ve spent a good part of my listening life since trying to get to the bottom of it.

Years later, I took you to see Kenny Barron play, and after the show you sat at the next table as I interviewed him. It was one of the proudest moments of my life—talking with my favorite pianist for a commissioned article, while my father looked on.

When you were diagnosed, when I researched your condition and read the statistics and realized how dire your prognosis was, I considered not listening to music for a while. Music leaves deep imprints on me, and I didn’t want to find a record that I loved, only to associate it with your death. Ultimately, it was a foolhardy consideration; I’ve listened to a lot of music, for comfort, for solace, or to find an expression for my rage or confusion.

But I can’t hear a love song, or a lost love song, or a goodbye song, without thinking of you and Mom. Under normal circumstances, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds—one of the records that marked the start of your relationship—would find its way onto my turntable maybe once a month; I can’t even look at it now. That new Dylan record I was telling you about—the one full of Sinatra songs—is another one. How can I hear something like ”Where Are You?” without thinking of her, having to live without you? All life through, must I go on pretending? / Where is my happy ending? / Where are you?

But I can’t hear a love song, or a lost love song, or a goodbye song, without thinking of you and Mom. Under normal circumstances, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds—one of the records that marked the start of your relationship—would find its way onto my turntable maybe once a month; I can’t even look at it now. That new Dylan record I was telling you about—the one full of Sinatra songs—is another one. How can I hear something like ”Where Are You?” without thinking of her, having to live without you? All life through, must I go on pretending? / Where is my happy ending? / Where are you?

I can’t imagine still loving someone, but having to leave her. I tell you we’ll take care of her; you needn’t worry. If you can hear me, I hope you know it’s true.

Now, your hand is limp in mine, and a song begins to play in my head, unbidden. I hear the singer’s voice, but it’s your voice, too. It’s a song from a movie I’ve never seen, but I imagine it playing in your movie, the one I can’t see. I imagine you singing it to us.

Let my love be no burden

Let me be your servant

Silent and certain as time ticking by

Like a star let it guide you

And hide it inside you

And know I’ll be by to protect you from harm

Be never afraid of dark shadows or shade

Let sad memories fade ’til you need them

And someday when you’re young again

We’ll play like we did back then

And fly far away, you and I, my friend

I hope you’re not afraid. I imagine my voice is just one in a chorus you’re hearing now, a collection of sounds keeping you comforted as you struggle. I imagine you’re hearing the ocean and wind chimes, a child’s laughter, the gentle patter of drizzle against a window. I hope you’re hearing harmony, of every sort.

I hope you’re not afraid. I imagine my voice is just one in a chorus you’re hearing now, a collection of sounds keeping you comforted as you struggle. I imagine you’re hearing the ocean and wind chimes, a child’s laughter, the gentle patter of drizzle against a window. I hope you’re hearing harmony, of every sort.

I hope whatever you’re seeing now is bright and warm and welcoming. I hope you’ll soon see the sun shine, and the first breath you draw is long and deep and redolent with familiar scents.

Wherever you go after this, I hope you’re young again, and whole, and happy.

Wherever it is, I hope it’s morning.

Comments