When do we ever feel more than we do as teenagers? Little hormone factories we are, punching at the walls, lifted off our foundations by feeling. Not feelings, the synonym for emotions that hack songwriters use when they’ve just used the word emotion two lines previous, or need a hook for the chorus (”whoa-whoa-whoa”). I’m talking about feeling—that cloud cover that settles down upon us when sadness overtakes us, or the brightest imaginable sunburst that blasts forth from us in the happiest of moments. Sometimes, the clouds and sun are separated by mere minutes, alternating dark and light, depending on whether a certain someone gives us the time of day, or smiles at us in the hall between classes, or answers the phone when we get up the nerve to call.

Close your eyes and remember fifteen, sixteen. Take a few minutes and put yourself back into that head space, that body, those clothes. That hair.

Remember?

Teens need an outlet for feeling, and more often than not, they’re stymied in their attempts to find it. Most adults’ hormonal cauldrons cool off, or they have more numbing agents at their disposal, or more people to talk to, or the right people to talk to. The kids don’t have those.

That’s where music comes in.

That’s where music comes in.

Music is a language the soul understands, filter-free, no translation necessary. It likewise connects directly to our bodies, to our internal rhythms, and we react to it in ways that render words useless (words—those other symbols that enable us to communicate our thoughts and desires to others). We are wired to respond. It could be the chill that shoots through us during the dramatic moments in a song—a modulation, a breakdown, a heart-pounding opening. It could be the desire to move our bodies in lock with a rhythm—a sensual sway of the hips, a syncopated nodding of the head, even a violent spasm of aggression. It could be the eyes that fill when a melody triggers a memory, of someone long gone but indelibly present, of a long-ago evening of desire fulfilled, of a day when we felt stronger, more together, better capable of handling anything.

Add to that the voices that bring melody, harmony and words to that music. I’m not even thinking about the lyrics—which can express so much, so many things we ourselves feel incapable of saying—but the human instrument, the timbre, the power, the subtlety, the breath of a song. When voice and music lock into one another, and both in turn lock into our heads and hearts as listeners, we experience the palpable result of that combination, the transmutation of that which can be heard into that which is felt, the peculiar alchemy that turns sound into emotion.

We know when it’s wrong, when it doesn’t work, when even the most beautiful melodies are put forth by a voice that cannot bring them to full flower, the dissonant results of so much promise.

But when it’s right—man, that’s the life-affirming stuff, sometimes the life-changing stuff. This is true in particular for teenagers, but not exclusively for them. Sometimes songs reach out across the years to touch those who are decades past their periods of greatest feeling. Sometimes voices that moved us as teens can crack us open as adults.

I grew up a fan of commercial rock—Journey, Foreigner, REO Speedwagon, Styx and the like. If you grew up where I grew up, when I grew up, and you listened to the radio, that music and those voices were there, were very present; they were a part of your experiences; they soundtracked a hundred adventures and slow dances and brought you around to a place of strength when you needed it, when you couldn’t find it within yourself, but only within the sounds coming out of your stereo or your radio.

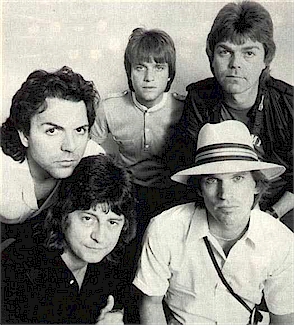

I wrote that last sentence in a Facebook post when Jimi Jamison died; Jamison was the voice of arena rock stalwarts Survivor, during their biggest commercial period (roughly 1984 to 1987). Jamison’s voice was a versatile instrument, to be sure—he could break your heart singing a ballad like ”The Search is Over” or ”Across the Miles,” but he could also blow the roof off your car if you were playing ”She’s a Star” or ”Can’t Let You Go” too loud.

Lately I’ve been listening a lot to Jamison’s predecessor in the band, Dave Bickler. His voice was one I had encountered first (of course, with ”Eye of the Tiger,” of the great Rocky III opening sequence and mid-inning entertainment at every baseball game I’ve ever been to), and one I’d continued to enjoy, even after his spot in the band had been relinquished.

Lungs of leather. Clarion tenor. Tiger in his eye; beret on his head. Streets beneath his feet; woman on his mind. When he was recording with Survivor, he was an American Paul Rodgers, and he could break rocks with his voice, if he so chose. It wasn’t a bluesy thing—it was pure power, pure arena-busting power, perhaps more so than any of his commercial rock brethren. You could imagine Dennis DeYoung doing Broadway musicals (albeit about robots and gatherings of angels); you could imagine Kevin Cronin doing soft songs in some Midwest coffee shop; you could imagine Steve Perry crooning Sam Cooke tunes in a cover band.

Bickler was great at being Bickler. He was the best Bickler, the biggest, Bicklerest of them all. He was created by the almighty fingers of the Stadium Rocker in the Sky Himself to hold a microphone in his hand and with only his voice break the glass doors on the other side of the arena, leveling a few thousand people fortunate enough to be in the way. Listen to ”Poor Man’s Son,” off the Survivor record Premonition. That’s what he used to sing to break the windows. The high note at the end of the chorus—that was what did the trick.

He could also steer the breakneck album openers that chief Survivor songwriters Jim Peterik and Frankie Sullivan provided him. Songs like ”Chevy Nights” (off Premonition) or ”Feels Like Love” (the real album opener on Eye of the Tiger; the title track was but a tacked-on single). They’re practically the same song—same pace and tempo, with lyrics about sex and cars, though in ”Chevy Nights” he’s looking back, and in ”Feels Like Love” he’s in the middle of ”gettin’ some action on a midnight ride,” which I’m sure we can all agree is not safe. Not safe at all.

But Bickler’s voice rides the wave, moving from declarative verses to exclamatory choruses with ease. The voice is polished, yes—Bickler put in his 10,000 hours in five-set-a-night clubs, and he knew his way around the material he was given, every curve and twist. But the edges of his voice still have some grain, still haven’t been sanded down, and when he reaches for the high notes, mostly in those choruses, it’s all edge. And it’s exquisite.

But Bickler’s voice rides the wave, moving from declarative verses to exclamatory choruses with ease. The voice is polished, yes—Bickler put in his 10,000 hours in five-set-a-night clubs, and he knew his way around the material he was given, every curve and twist. But the edges of his voice still have some grain, still haven’t been sanded down, and when he reaches for the high notes, mostly in those choruses, it’s all edge. And it’s exquisite.

He could do dynamics, too. ”I’m Not That Man Anymore” (from Eye of the Tiger) starts out in the ether, with just voice and piano, picks up momentum four lines in, with a struck hi-hat and more keyboard, and you can sense the tension in Bickler’s voice ramping up, beckoning the drums to present themselves, the guitar to come forth, into the chorus when he breaks the song open. The kill shot is the end of the second chorus, when he takes the line ”Baby, I’ve changed” and elongates the last syllable, holds it, does the little melisma thing to it, but it’s rough. It’s Rodgers rough. It’s unsanded-edge rough. It’s blast-the-glass intense, an arena-slaying moment that I’ll bet he never broke a sweat laying down onto tape. You or I on our best days could get up at some karaoke thing at the local tavern, or step into a shower with tremendous acoustics, and attempt to imitate that kind of power, that kind of effortless proficiency. Could we ever achieve it? For real? As my Southern friend used to say, ”Aw, HELL, naw.”

There’s more, of course. There’s ”Silver Girl,” where he stays in that high vocal register—keeps the thing going for the entire song, front to back, and launches one of the two or three best songs Peterik and Sullivan ever wrote past the stratosphere, clear up to the sun. There’s ”Ever Since the World Began,” the wise and moving ballad of the progression of life, with a suitably weighty lyric Bickler delivers with all reverence and authority. There’s ”Slander,” an angry take on the damage rumors can have on relationships, and Bickler sings in a measured voice, so as to seethe that much more convincingly.

These and other songs were among those I listened to when I needed to be connected to something, when I needed a channel my frustration or lust or confusion or even when I just wanted to get in a car with my friends and experience some modicum of freedom. When I wanted to feel. Dave Bickler provided the voice that helped me feel. Not sure how I’da gotten out of my middle teens without that voice.

Today is his birthday.

Happy birthday, Mr. Bickler. And thank you.

Comments