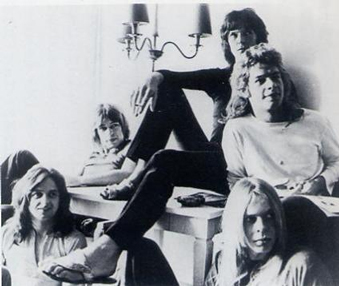

Beauty, it is said, is in the eye of the beholder; to each his or her own; different strokes for different folks; one man’s trash is another’s treasure; you ain’t a beauty, but hey, you’re all right. All this I mention in the interest of noting that the five guys in Close to the Edge-era Yes were not conventionally handsome blokes (with the exception, I suppose, of drummer Bill Bruford, who shouldn’t count, because the drummer always gets first pick of the chicks, unless you were the drummer in Blue Oyster Cult; in that case, it was the drummer for the opening band who got dibs on the babes). Jon Anderson was a harp-strokin’ elf who could quote from Paramahansa Yogananda’s footnotes as easily as Bon Scott could quote a filthy limerick. Steve Howe looked like Margaret Hamilton in full witchy-poo regalia, minus the green skin. Chris Squire could have used some green tannin; his froggy lips stood out against his pasty pallor. And if the be-caped Rick Wakeman wasn’t auditioning for the role of Merlin in Unidentified Flying Oddball, he sure as hell dressed the part.

Beauty, it is said, is in the eye of the beholder; to each his or her own; different strokes for different folks; one man’s trash is another’s treasure; you ain’t a beauty, but hey, you’re all right. All this I mention in the interest of noting that the five guys in Close to the Edge-era Yes were not conventionally handsome blokes (with the exception, I suppose, of drummer Bill Bruford, who shouldn’t count, because the drummer always gets first pick of the chicks, unless you were the drummer in Blue Oyster Cult; in that case, it was the drummer for the opening band who got dibs on the babes). Jon Anderson was a harp-strokin’ elf who could quote from Paramahansa Yogananda’s footnotes as easily as Bon Scott could quote a filthy limerick. Steve Howe looked like Margaret Hamilton in full witchy-poo regalia, minus the green skin. Chris Squire could have used some green tannin; his froggy lips stood out against his pasty pallor. And if the be-caped Rick Wakeman wasn’t auditioning for the role of Merlin in Unidentified Flying Oddball, he sure as hell dressed the part.

U-G-L-Y: the Yes-men had no alibi. Yet, I argue that the music they made contained moments of exquisite, perhaps overwhelming, beauty. And I offer Side One of the aforementioned Close to the Edge as Exhibit A. Say what you will about prog, its pretensions, its pseudo-classicism, its swordplay and faerie-wooin’, and its off-putting bombast. You’re right about all of it, sure as Greg Lake’s corset cries for mercy to this very day. But there is also beauty amid prog’s clamor. Exhibit B: Soft Machine’s Third. Exhibit C: Camel’s The Snow Goose. Exhibit D: the Strawbs’ Bursting at the Seams. You betcher Tarkus, boys ‘n’ girls.

Back to Exhibit A. “Close to the Edge” has just about everything prog-haters decry in their run-ins with the stuff. First of all, it’s not just a song, but a side-long, four-part, 18-minute suite (already, you’ve lost the three-minutes-and-out pop folks). Secondly, its lyrics are gibberish (Dylan and Kristofferson folks have just cleared the room, though the Leonard Cohen set are sticking around, just out of curiosity). Third, it begins with a completely bombastic, explosively fartastic three minutes of sturm und drang, gee-tar-twiddlin’ twaddle (which clears out the Allmans’ fans, though a 20-minute blues solo typically has more than its share of fartasm). It also includes the castrato-testification of Jon Anderson, supplemented by Chris Squire’s slightly lower-timbre mirror vocalizin’ (alienating fans of singing, in general).

But it’s beautiful. Absotively, posolutely beautiful, and it so perfectly entices the listener to slide into the spiky yet tuneful prog of Close to the Edge, the album. Yes have made some other quality records (Relayer, Fragile, Going for the One, Drama) and some not-so-great ones (Tormato and … well, Tormato—so bad it should count twice), but none grab the ears quite the same way as Close to the Edge does.

But it’s beautiful. Absotively, posolutely beautiful, and it so perfectly entices the listener to slide into the spiky yet tuneful prog of Close to the Edge, the album. Yes have made some other quality records (Relayer, Fragile, Going for the One, Drama) and some not-so-great ones (Tormato and … well, Tormato—so bad it should count twice), but none grab the ears quite the same way as Close to the Edge does.

Side One is the money shot, minus all that pesky foreplay (I know, that’s a disgusting image when placed in the same column with a discussion of Steve Howe and Chris Squire’s looks). The song begins with a pastoral soundscape, with water rushing and birds chirping and synthesized wind chimes chiming, a new-agey intro that explodes into a storm, a maelstrom of noise and whomping percussion—in prog terms, total freakout shit. It’s hard to keep up with what Howe’s fingers are doing; it’s all independent of any melody, or of anything being played by Wakeman at the moment. Squire tries to keep up, gives up, and eventually goes his own way as well. Only Bruford seems to be keeping any real consistency in his contribution. A choir of heavenly Andersons chimes in, in relief, with a lovely “Aaaah,” as in “Ah, a respite from the chaos. Let me sing, ‘Ah’ again!” And he does. Or they do—the choir of heavenly Andersons.

The dissonance comes to a crescendo and falls into the first main theme of the song, where syncopated guitar and gurgling bass give way to the first lyrics of the track. And oh, what lyrics they are:

A seasoned witch could call you from the depths of your disgrace,

And rearrange your liver to the solid mental grace,

And achieve it all with music that came quickly from afar,

Then taste the fruit of man recorded losing all against the hour.

And assessing points to nowhere, leading every single one.

A dewdrop can exalt us like the music of the sun,

And take away the plain in which we move,

And choose the course you’re running.

Down at the edge, round by the corner,

Not right away, not right away.

Close to the edge, down by a river,

Not right away, not right away.

Now, the English-speaking among us can feel completely justified in responding to such a verbal osmotic bowel expulsion with a robust “What the fuck?” Turns out that Anderson—Yes’ chief lyricist—loosely based “Close to the Edge” on Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, to which Hesse, had he survived another ten years in order to hear Anderson’s tribute, would likely have also responded with a robust “What the fuck?” Time and several confessional interviews have revealed Anderson’s lyrical penchant for using words for their sounds and cadences, as opposed to, you know, their meaning. That’s right, folks, he wrote the line, “And rearrange your liver to the solid mental grace” because it sounded good.

Now, the English-speaking among us can feel completely justified in responding to such a verbal osmotic bowel expulsion with a robust “What the fuck?” Turns out that Anderson—Yes’ chief lyricist—loosely based “Close to the Edge” on Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, to which Hesse, had he survived another ten years in order to hear Anderson’s tribute, would likely have also responded with a robust “What the fuck?” Time and several confessional interviews have revealed Anderson’s lyrical penchant for using words for their sounds and cadences, as opposed to, you know, their meaning. That’s right, folks, he wrote the line, “And rearrange your liver to the solid mental grace” because it sounded good.

Onward the song wends through its first two sections, code-named “The Solid Time of Change” and “Total Mass Retain” (recalling the “total mass retention” teachings of the Gautama Buddha, who ameliorated the extreme asceticism of Sramana faiths by encouraging his followers to eat Snickers bars. Yes, I just made that up), into the churchy waft of the third section, “I Get Up, I Get Down.” The segment begins with dripping water effects and atmospheric synth chords—maybe we’re in a cave; maybe the cave is in us. Squire and Anderson trade vocal leads that start on this ponderific note:

In her white lace, you could clearly see the lady sadly looking.

Saying that she’d take the blame

For the crucifixion of her own domain.

I get up,

I get down,

I get up,

I get down.

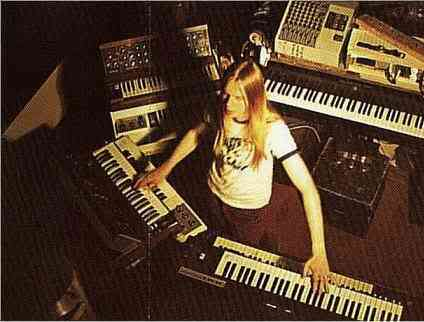

I’ve dated a few women with crucified domains in my time, but none of them were as pretty as the sounds the band coaxes from their instruments during this portion of the song. Rick Wakeman is really the star of this piece, shuttling from synth to cathedral organ to Hammond organ, round and round again. Indeed, his work here lends credence to the rumor that he hid eight arms under his wizard cloak—two to play the cathedral organ, two to alternate between Mellotron and Moog, two to play the Hammond B-3, one to pick the cape wedgie out of his buttocks, and one to hold the massive turkey leg from which he drew protein and sustenance during these long fucking songs.

I’ve dated a few women with crucified domains in my time, but none of them were as pretty as the sounds the band coaxes from their instruments during this portion of the song. Rick Wakeman is really the star of this piece, shuttling from synth to cathedral organ to Hammond organ, round and round again. Indeed, his work here lends credence to the rumor that he hid eight arms under his wizard cloak—two to play the cathedral organ, two to alternate between Mellotron and Moog, two to play the Hammond B-3, one to pick the cape wedgie out of his buttocks, and one to hold the massive turkey leg from which he drew protein and sustenance during these long fucking songs.

It all comes crashing back into the fourth section, for some reason dubbed “Seasons of Man,” which returns to the “Total Mass Retain” theme, with the bass figures from the first two sections repeated and more imponderables pondered in the gibberish lyrics. It all ends where it began, though—with the synthesized sounds of nature cascading all around us, getting up and getting down. My God, but I can imagine the prototypically spaced-out teenager listening to this thing on headphones back in 1972, stoned off his gourd, closing his eyes and seeing the Buddha delivering takeout manna to Jesus and Ridwan and Rin Tin Tin somewhere in his own temporal lobes. It’s ridiculous and impenetrable and also beautiful, the former two feeding into the latter with alarming and appealing strength.

And that’s just Side One. Flip the record over, and you have another four-part epic to greet you—“And You and I.” Though half as long as “Close to the Edge,” it possesses as many gorgeous moments, and as much outlandish lyrical absurdity. And then there’s “Siberian Khatru,” classic rock and guitar nerd staple with the exquisitely nonsensical refrain, “Even Siberia goes through the motions.” It also ends with a dance between Wakeman’s spacey synths and Howe’s clean-toned guitar, a swirling tandem that concludes the record on a note of splendor that befits all that precedes it.

Close to the Edge might not convince prog’s detractors, but to the converted, it’s a grand thing, indeed.

Comments