As literary figures go, Sherlock Holmes, birthed in 1887, has been well-served by 20th century media. Looking through my DVD and Blu-ray shelves I can find numerous good adaptations, some traditional and some free, ranging from the Basil Rathbone pictures in the 30s and 40s beloved by me and my dad to The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), A Study in Terror (1965), They Might Be Giants (1971), and The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976). On TV, Sherlock and Elementary have brought the sleuth into our era of social media. (And Robert Downey, Jr. has turned him into an action figure, not one of his more rewarding modes.)

As literary figures go, Sherlock Holmes, birthed in 1887, has been well-served by 20th century media. Looking through my DVD and Blu-ray shelves I can find numerous good adaptations, some traditional and some free, ranging from the Basil Rathbone pictures in the 30s and 40s beloved by me and my dad to The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), A Study in Terror (1965), They Might Be Giants (1971), and The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976). On TV, Sherlock and Elementary have brought the sleuth into our era of social media. (And Robert Downey, Jr. has turned him into an action figure, not one of his more rewarding modes.)

Now comes Mr. Holmes, which, sometime in my declining years, I look forward to seeing in repertory with Young Sherlock Holmes (1985). For this is old Sherlock Holmes, 93 in fact, and retired quietly to the seashore near Dover. The year is 1947, Watson is no longer on the scene, and the detective busies himself with his apiary. A final case, however, twinges his fading memory. The game is afoot…but, due in part to limitations of body and mind that Ian McKellen delicately plays, it’s more a game of the mysteries of the heart, an organ too long unattended by Holmes. In the present day, Roger (Milo Parker), the son of the detective’s landlady Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney), endeavors to learn more of her world-famous employer, who has made a certain peace (and only a certain peace) with living a life that is half fact and half fiction. There are reminiscences of a recent journey to Japan, in search of revivifying “prickly ash jelly,” in the company of Umezaki (Hiroyuki Sanada), who wants Holmes to clarify some murky details of his father’s time in England. And there is that vexing case, of a concerned husband, an apparently faithless wife (Hattie Morahan), and their two children, both prematurely deceased. A doctor asks Holmes to checkmark any memory slips–soon the ledger is filled with checks, as Holmes struggles to break through a fog as thick as any in London.

Adapted from a novel by playwright Jeffrey Hatcher (Stage Beauty, and also a play about Holmes, plus episodes of Columbo and The Mentalist), Mr. Holmes reteams McKellen with Bill Condon, the director of the outstanding Gods and Monsters (1998), which won Condon an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay and gave the Oscar-nominated actor a home in Hollywood movies after a false start or two earlier in his career. The wit and dash of the earlier film, which was colored with gayness and classic horror, have been replaced by a statelier look and more autumnal pacing. After his sojourn with the Twilight saga and the ill-suited biopic The Fourth Estate, Condon, thankfully, returns to his roots as a teller of more intimate tales, laced with spookiness. (All the way back to 1981’s Strange Behavior.) In one of the film’s best scenes, Holmes, used to drawing room crimes, is confronted by a 20th century horror in Japan, almost beyond even his comprehension; in another, he deduces a potentially awful fate for Milo, who (winningly played by Parker) has become his friend and confidante, and rushes to save him despite his infirmities.

But Mr. Holmes is a quiet movie, roiled only by the desperate appearance of the needle, and the misunderstood emotions of Mrs. Munro, played at a slow boil by Linney, and the lady at the center of the case. Off to a fast start at the boxoffice, it does have a few tricks up its sleeve, however, including references to Hitchcock, and one marvelous in-joke, when Holmes goes to see a Sherlock Holmes movie. It could have been a Basil Rathbone one (the series was just wrapping up then) and I was disappointed that it wasn’t. Condon’s fictional entry, in black and white, then trumps expectations with its casting of the lead role. Well played, Mr. Holmes, well played.

Irrational Man has been called Woody Allen’s worst movie ever. It isn’t. (That would be 2007’s Cassandra’s Dream.) And it is better, or at least a bit shorter, than last year’s Magic in the Moonlight, one of his spiritualism things, which tend to be ectoplasm-thin. (Scoop, A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger–believe me, I know lackluster Woody Allen.) Granted that’s hardly great news for anyone hoping for a Midnight in Paris or Vicki Cristina Barcelona, or a strong central performance like Cate Blanchett’s in Blue Jasmine. This is one of his sketchy scripts, the ones pulled hot out of the Olivetti and thrown into production before it was allowed to settle and deepen.

Irrational Man has been called Woody Allen’s worst movie ever. It isn’t. (That would be 2007’s Cassandra’s Dream.) And it is better, or at least a bit shorter, than last year’s Magic in the Moonlight, one of his spiritualism things, which tend to be ectoplasm-thin. (Scoop, A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger–believe me, I know lackluster Woody Allen.) Granted that’s hardly great news for anyone hoping for a Midnight in Paris or Vicki Cristina Barcelona, or a strong central performance like Cate Blanchett’s in Blue Jasmine. This is one of his sketchy scripts, the ones pulled hot out of the Olivetti and thrown into production before it was allowed to settle and deepen.

As Mia Farrow resumed her fatwa against Allen last year it was rumored that Irrational Man was going to push a few buttons, being the story of a 40-year-old college professor (Joaquin Phoenix) having an affair with a student (Emma Stone). It is that, but, really, it’s not. There is a relationship between Abe Jacobs (Phoenix), a washed-up philosophy prof who turns up, drunk and suicidal, at a lovely college in Newport, R.I., and the sensible Jill (Stone), the daughter of two faculty members. The soft, pot-bellied Phoenix and Stone, an old soul who can take care of herself, aren’t cringeworthy as lovers, however, and that side of the story is barely elaborated upon. The one element Allen nails in Irrational Man is the gossipy side of smalltown college campuses. In its key scene, Jill, trying to distract Abe from his funk, encourages him to listen in on a conversation at a diner, where a distraught mother is holding forth about the unfair judge ruling against her on child custody issues. Perhaps enacting a scenario that Allen might have considered in his tabloid prime, Abe, in the thrall of Crime and Punishment, decides to bump off the judge, which immediately relieves his depression, though it soon creates headaches for Jill and Rita (Parker Posey), the frowsy professor’s wife he’s also sleeping with.

If the notion of homicide as life-enhancing sounds a little familiar, it’s because Allen is reworking ground covered far more successfully in 1989’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, one of his best films. Phoenix is basically a younger, guilt-free version of Martin Landau’s character, and within severe limitations placed by Allen’s scant, voiceover-heavy scripting he’s amusing to watch, pursuing women and career with newfound zeal. Despite a mild autobiographical resemblance, Phoenix is very good at not playing a Woody stand-in, which is the movie’s other strength. Other than that, well, it’s murder–Posey, who reinvigorated her career via Louie, gets one or two of the movie’s stray laughs (it’s not a comedy) but isn’t allowed to build on that small-screen triumph, and a third-act turn into a suspense story is ludicrous, ineptly written and staged. If only Bill Condon or someone with those credentials had been brought in to co-write. The biggest mystery, however, is why Allen can’t get anything going with Stone, in their second stillborn movie together. Like Diane Keaton and Scarlett Johansson before her she seems like an ideal muse, game for anything he might throw her way. But these are grounders, unworthy of her beauty and talent, and the Irrational Man is Woody, for squandering such a resource on second-hand goods.

Time now to look at some of my favorite viewing of the year to date, now on DVD and Blu-ray.

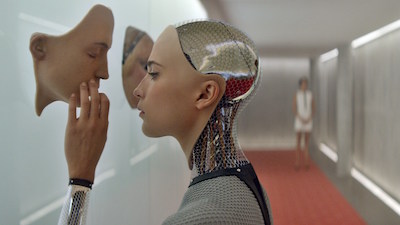

Ex Machina emerged as one of the year’s biggest indie hits, which should warm the hearts of sci-fi fans exasperated with retreads and reboots. Not that there’s much warming about it; that a film so cool, nuanced, and distanced found an audience at all is especially gratifying. In the Kubrick vein, writer and director Alex Garland (scripter of the equally engaging 28 Days Later and Dredd) has made one of the most intelligent android movies, a stealthy mystery about identity and other variables we only think we can put under our control. There are three characters–an eccentric scientist (Oscar Isaac), an eager apprentice (Domhnall Gleeson), and the scientist’s creation (Alicia Vikander)–confined to one setting, yet their interaction plays out in unpredictable ways that open our minds to interpretation about the eternal question of what it means to be human. The Blu-ray, an object of mechanized beauty in its look and sound, has some excellent back-and-forth with Garland and Isacc, among other principals, and a host of behind-the-scenes footage.

Ex Machina emerged as one of the year’s biggest indie hits, which should warm the hearts of sci-fi fans exasperated with retreads and reboots. Not that there’s much warming about it; that a film so cool, nuanced, and distanced found an audience at all is especially gratifying. In the Kubrick vein, writer and director Alex Garland (scripter of the equally engaging 28 Days Later and Dredd) has made one of the most intelligent android movies, a stealthy mystery about identity and other variables we only think we can put under our control. There are three characters–an eccentric scientist (Oscar Isaac), an eager apprentice (Domhnall Gleeson), and the scientist’s creation (Alicia Vikander)–confined to one setting, yet their interaction plays out in unpredictable ways that open our minds to interpretation about the eternal question of what it means to be human. The Blu-ray, an object of mechanized beauty in its look and sound, has some excellent back-and-forth with Garland and Isacc, among other principals, and a host of behind-the-scenes footage.

We may soon be losing Isaac, someone I’ve liked since his earliest Off Broadway roles, to Star Wars and fame. Double dip and enjoy him and Jessica Chastain in A Most Violent Year, a most terrific thriller, albeit one in the hushed, underlit manner of Sidney Lumet–the violence, as Isaac’s self-made heating oil magnate is forced to deal with underhanded competitors and even more unscrupulous government investigators (led by Selma‘s David Oyelowo), is a slow build, and when it comes it explodes close to home. (Albert Brooks is Isaac’s attorney, a keeper of secrets). While Chastain goes on a tear with the New Yawk accent and costuming (it’s 1981, the baddest of the bad old days in the Big Apple), Isaac pulls back, like Al Pacino when he barely spoke above a commanding murmur. (Remember that?) Hear from the stars, plus writer/director J.C. Chandor (of Margin Call and All is Lost), and learn something of the history of the era in the Blu-ray’s extensive supplements.

Speaking of upending a tired genre: It Follows. A film with the intensity of a waking nightmare (writer/director David Robert Mitchell based it on his own dark dreams), it plays even better on the spotless Blu-ray, where you can track the comings and goings of characters moving in and out of the widescreen frame–randomly, or looking for the next victim of the “sex curse” that won’t leave the heroine alone? There’s a lot to look at here, including the off-kilter production design (when are we?), an effective use of Detroit locations, which move from placid to scarifying in the blink of an edit, and the throwback, John Carpenter-ish music, by Disasterpiece. The score gets its own extra; the commentary, unusually, is by web critics whose advocacy helped make It a hit, and while the open mic format is a bit distracting, they don’t screw up the opportunity.

Speaking of upending a tired genre: It Follows. A film with the intensity of a waking nightmare (writer/director David Robert Mitchell based it on his own dark dreams), it plays even better on the spotless Blu-ray, where you can track the comings and goings of characters moving in and out of the widescreen frame–randomly, or looking for the next victim of the “sex curse” that won’t leave the heroine alone? There’s a lot to look at here, including the off-kilter production design (when are we?), an effective use of Detroit locations, which move from placid to scarifying in the blink of an edit, and the throwback, John Carpenter-ish music, by Disasterpiece. The score gets its own extra; the commentary, unusually, is by web critics whose advocacy helped make It a hit, and while the open mic format is a bit distracting, they don’t screw up the opportunity.

Foreign films are in dire straits at the U.S. boxoffice, with few breaking through. Fortunately home video is netting a few good ones before they disappear entirely. The Italian-made Human Capital is one of those everything-is-connected melodramas, like Crash or Babel, but it uncoils like a serpent, and bares sharper fangs. The movie starts with a middle-aged, middle-class working stiff’s fumbling attempts to ingratiate himself with a family of nouveau riche bankers, whose appearances are calculated to deceive, then spirals outwards into a societal critique that leaves no stone unturned as survival instincts trump common sense and morality. I’ll say no more; this one will grab you. (And Rain Man co-star Valeria Golino is in it, still fetching.) Extras include an informative making-of. Film Movement deserves full credit for keeping overseas cinema alive and well on these shores.

Well Go USA continues to walk on the wild side of Asian cinema. From Korea, For the Emperor is a decent if unspectacular action yarn with a distinct film noir flavoring, as a baseball player who’s washed out of the game goes to work for a loan shark at Emperor Capital, gradually accumulating his own power base. When his barkeep girlfriend vanishes, however, it’s batter up as the protagonist pursues his mentor in crime. Good for an evening’s entertainment anyway.

Better is the Hong Kong thriller Kung Fu Killer, starring Donnie Yen, who has also been drafted into the Star Wars universe. Yen, who doesn’t need a light saber to be completely awesome, is a martial artist, jailed for killing another martial artist, who breaks out to track down a martial artist who’s killing other martial artists–which is all you need for a rock ’em sock ’em romp with episode after episode that’s crazier than the next (fossil fighting!), punctuated with starry cameos. It’s Ten Little Indians with a plethora of kung fu styles, and what more do you need, anyway? Well Go prices its titles fairly, and if the description intrigues you, go for the blind buy and say you knew Yen when as the force goes with him.

Better is the Hong Kong thriller Kung Fu Killer, starring Donnie Yen, who has also been drafted into the Star Wars universe. Yen, who doesn’t need a light saber to be completely awesome, is a martial artist, jailed for killing another martial artist, who breaks out to track down a martial artist who’s killing other martial artists–which is all you need for a rock ’em sock ’em romp with episode after episode that’s crazier than the next (fossil fighting!), punctuated with starry cameos. It’s Ten Little Indians with a plethora of kung fu styles, and what more do you need, anyway? Well Go prices its titles fairly, and if the description intrigues you, go for the blind buy and say you knew Yen when as the force goes with him.

Veteran Hong Kong action stylist Tsui Hark returns with The Taking of Tiger Mountain, which loses a point for not being available in its native 3D. The filmmaker rocks hard in the format, and I may have to track down a more dimensional disc. That said this is an era-spinning “mission movie,” rooted in Chinese history and set following World War II, which pits People’s Liberation Army fighters against a vicious gang that has taken control of a massive fortress. The structure of the movie is cumbersome, the politics a little dicey (HK movies having become something of a vessel for mainland propaganda), but rest assured that Tiger Mountain gets taken, which is good news for action buffs.

Comments