There are movies playing now that maybe I should see, but I’m not seeing them. I blame The Social Network for spoiling my usual appetite—after the feast, why go back the thinner gruel of jackasses and paranormal activities and saws?

There are movies playing now that maybe I should see, but I’m not seeing them. I blame The Social Network for spoiling my usual appetite—after the feast, why go back the thinner gruel of jackasses and paranormal activities and saws?

This would seem to be an obvious problem for a Film Editor. Got it covered, though. I haven’t been entirely negligent: I spent the end of the New York Film Festival in the disarming company of Joe Dante, who was screening his latest ”therapeutic horror movie,” The Hole, in 3D, and greeted this week’s DOC NYC fest with Werner Herzog’s eye-opening 3D exploration of the paintings at Chauvet Cave, Cave of Forgotten Dreams. (Between them these two films reawaken artistic interest in the process.) After a 15-year absence—the length of two Kubricks, and almost a Malick—England’s Philip Ridley has returned with a strong (and touching) new thriller, Heartless, which opens Nov. 19.

Mostly I’ve been letting the new movies come to me, or as close to me as I can get. Unless you’ve been living under a Swedish meatball you’ve surely heard of the late Stieg Larsson’s selling-like-lingonberry jam Millennium trilogy and its first filmic progeny The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, the country’s hottest export since Ikea. Tattoo introduced us to disgraced investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist) and computer hacker and Jill of all trades Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace), who teamed up over e-mail to ferret out pedophiliac secrets intricately tied to old money. Salander did most of the heavy lifting, which included a brutal S&M turning-of-the-tables that would not have been out of place in the most downmarket torture porn, then (SALANDER SPOILER) made off with a rotter’s ill-gotten gains.

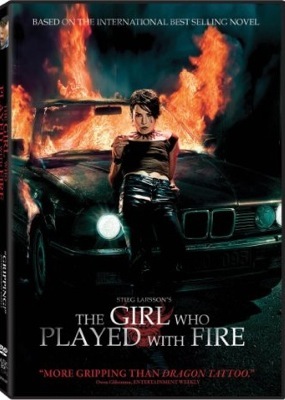

In the sequel, The Girl Who Played with Fire, Salander is back to shake the ramparts of power in sleepy Stockholm, which the filmmakers don’t even try to turn into a nourish Sin City. Also back is the mopey, fretful Blomkvist, who mopes and frets a lot in this one, too, as he and the stealthy Salander sleuth a sex trafficking ring right into the heart of darkness—our girl’s tortured, and torturing, family. This requires Salander to dress up like a member of the mime group Mummenschanz, participate in another, lesser sado-revenge, and endure more punishing beatings. Larsson wrote his thick books in a white-hot rage against his sex (Dragon Tattoo’s original title translates to the unenchanting Men Who Hate Women) and it’s hard not for a male viewer to watch them without a slight twitch, no matter that this one has a mid-hot lesbian sex scene to mollify us. (Film buffs can get off on seeing Sven-Bertil Taube and Per Oscarsson, who had international careers in the 60s and the 70s, in these movies.)

In the sequel, The Girl Who Played with Fire, Salander is back to shake the ramparts of power in sleepy Stockholm, which the filmmakers don’t even try to turn into a nourish Sin City. Also back is the mopey, fretful Blomkvist, who mopes and frets a lot in this one, too, as he and the stealthy Salander sleuth a sex trafficking ring right into the heart of darkness—our girl’s tortured, and torturing, family. This requires Salander to dress up like a member of the mime group Mummenschanz, participate in another, lesser sado-revenge, and endure more punishing beatings. Larsson wrote his thick books in a white-hot rage against his sex (Dragon Tattoo’s original title translates to the unenchanting Men Who Hate Women) and it’s hard not for a male viewer to watch them without a slight twitch, no matter that this one has a mid-hot lesbian sex scene to mollify us. (Film buffs can get off on seeing Sven-Bertil Taube and Per Oscarsson, who had international careers in the 60s and the 70s, in these movies.)

The director of Dragon Tattoo, Niels Arden Oplev, has lambasted the director of Played with Fire and the just-opened The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, Daniel Alfredson (older brother of Let the Right One In director Tomas Alfredson), for hackwork and opportunism, as if Dragon Tattoo was The Seventh Seal or some other zenith of artistic expression. It isn’t: I’ve read none of the books but like the Harry Potters the film version would seem to suffer for an overzealous fidelity, running as it does a posterior-punishing 152 minutes, and like the Potters a lot happens while nothing much seems to go on. The movie could be condensed to two hours, a goal that Played with Fire, which I watched on an extras-less screener DVD, comes closer to fulfilling. (It’s also on Blu-ray.)

Fire, though, is less satisfying as a genre entertainment. I’d say this is one of those cases where the fault is more in what’s being adapted than the adaptation, not that it’s anything above a potboiler. I get the appeal of Dragon Tattoo, which, with its multiple suspects, is like a spicier, spikier version of Agatha Christie, and Rapace, who’s receiving the Hollywood build-up, is as riveting as a jungle cat as the multifaceted Salander. We don’t make these kinds of mysteries anymore, and good for Music Box Films, the distribution arm of the great Chicago arthouse, for spotting its potential and running with it (the outfit had some experience, with its successful handling of Tell No One). Good, too, for large audiences to be reading, subtitles as well as books. For the intimidated, David Fincher (him again) is directing the U.S. remake, with Social Network co-star Rooney Mara and Daniel Craig, who I can only hope has more to do than stare into a laptop and carry Salander’s water for the duration.

That’s a real problem with the fizzle of Fire, a more generic conspiracy yarn for all the incestuous kinks, with one melted face bad guy and another who can’t feel pain, like the villain in the Bond picture The World is Not Enough. The two leads never really connect and when they do the movie just stops, as if winded, catching its breath for Salander to kick the hornet’s nest. She better give it a good hard kick to jump-start this unleavened, uneven series. Here’s its trailer; it may be that the most shocking thing about is its print ad, which shows Salander breaking an American cultural taboo and (gasp!) smoking. Playing with fire indeed.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/auMUTwFBomU" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

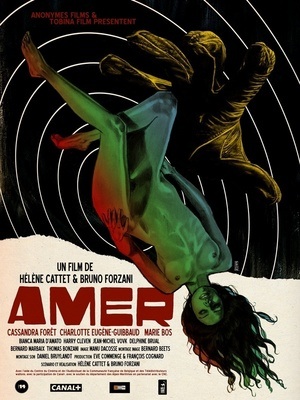

If Salander thinks she has problems, she should see what Ana goes through in Amer. As a child, the protagonist of the French-Belgian co-production is disturbed by her grandfather’s death, and seeing her parents having sex around the same time; as a teen she’s bothered by a motorcycle gang; and as an adult she’s stalked by a razor-wielding psycho through the family villa, which was once tended by witchy servants and is now dilapidated and overgrown. Well, OK, the tightly wound and ever-resourceful Salander would probably do just fine under these circumstances; Ana is a hot mess, not that the film, largely silent except for a jukebox full of thriller themes, means to get us close to her.

Amer (French for ”bitterness”) is an ingeniously contrived non-narrative feature concocted by HÁ©lÁ¨ne Cattet and Bruno Forzani, spun from the seductively suspenseful imagery and music of Italian giallo chillers from the 60s and 70s, specifically the films of the great Mario Bava (Blood and Black Lace, Bay of Blood) and Dario Argento (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red). It has everything genre enthusiasts like me want from a movie like this: Attractive, imperiled women gorgeously photographed in widescreen (by Manu Dacosse), liberal use of color filters and gels, Bava-style, and all sorts of fetishistic close-ups of eyes, razors, small insects, etc. All that’s absent is the convoluted plot, replaced by unfathomable longings. It’s a far more stimulating film than Argento’s latest, straight-to-DVD disappointment, titled Giallo but hardly the definitive last word on the subject we might have expected from the 70-year-old maestro.

Amer (French for ”bitterness”) is an ingeniously contrived non-narrative feature concocted by HÁ©lÁ¨ne Cattet and Bruno Forzani, spun from the seductively suspenseful imagery and music of Italian giallo chillers from the 60s and 70s, specifically the films of the great Mario Bava (Blood and Black Lace, Bay of Blood) and Dario Argento (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red). It has everything genre enthusiasts like me want from a movie like this: Attractive, imperiled women gorgeously photographed in widescreen (by Manu Dacosse), liberal use of color filters and gels, Bava-style, and all sorts of fetishistic close-ups of eyes, razors, small insects, etc. All that’s absent is the convoluted plot, replaced by unfathomable longings. It’s a far more stimulating film than Argento’s latest, straight-to-DVD disappointment, titled Giallo but hardly the definitive last word on the subject we might have expected from the 70-year-old maestro.

Amer adds to the dialogue, though what it has to say about the fusion of sex and violence and ”the discovery of the body, of desire, of sensuality,” as the co-directors put it, is intentionally opaque. And purists may object to its many quick cuts, as the filmmakers take a straight razor to the long tracking shots and carefully crafted sequences that distinguished the genre. No one, however, will complain about Amer’s use of vintage compositions by Ennio Morricone, Bruno Nicolai, and Stelvio Cipriani, heard in all their sexy, scary swagger. For Ana, and admirers of the form, they’re to die for. And that intoxicating poster—even without the trippy movie to support it supplies a rush all its own.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/KbcCsoMqVRk" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

The western is another genre given up for dead in these here parts. Galloping to the rescue is Red Hill, a thrill-packed ”Aust-ern” from down under, starring a local boy made good, True Blood co-star Ryan Kwanten. The oversexed Jason Stackhouse is playing at lawman on the show, but here Kwanten is the real deal, a rookie cop dispatched to the one-horse town of the title to join its long-entrenched force. Shane Cooper’s fateful first day brings the jailbreak of a convicted murderer, Jimmy Conway—which throws the grizzled veterans into a panic. Before you can say ”first blood” the crafty Jimmy has knocked off several members of the old guard, leaving Cooper relatively unharmed in their encounters. With his pregnant wife alone at home it’s up to the greenhorn to defuse the deadly situation.

Patrick Hughes wrote, produced, directed, and edited Red Hill, and was probably so tired from wearing all those hats you can’t blame him for leaning on fairly generic material for his feature debut. I mean, ”Shane Cooper,” that’s wearing it on your sleeve to suggest that your lead is a hero in the mold of Alan Ladd’s immortal gunslinger and the star of High Noon (so is naming your villain after a goodfella). Hughes and his star, huskier than on True Blood, make it count for something, however. (Does Kwanten live up to the name Shane Cooper? He wears it pretty well; it may help that behind his baby face is a 34-year-old who has been acting since his teens.)

Red Hill is one stripped-down, bad to the bone movie. Sure it references other westerns, and other types of movies, besides (it put me in mind of 1969’s The Stalking Moon, a ”horror western” with Gregory Peck trailing a remorseless Apache) but it does so stylishly, and like executive producer Greg McLean’s slasher opus Wolf Creek (2005) and killer croc flick Rogue (2007) it puts a native spin on the usual tropes. Conway is an Aborigine, and the film’s exciting climax, where white hat and black hat realize the grayness of their situation, manages a moving double resonance.

Red Hill is one stripped-down, bad to the bone movie. Sure it references other westerns, and other types of movies, besides (it put me in mind of 1969’s The Stalking Moon, a ”horror western” with Gregory Peck trailing a remorseless Apache) but it does so stylishly, and like executive producer Greg McLean’s slasher opus Wolf Creek (2005) and killer croc flick Rogue (2007) it puts a native spin on the usual tropes. Conway is an Aborigine, and the film’s exciting climax, where white hat and black hat realize the grayness of their situation, manages a moving double resonance.

I saw the movie under diminished circumstances (a watermarked screener), where it still played very effectively, and can only imagine how much better Tim Hudson’s widescreen photography and Enzo Iacano’s production design will look on the big screen when the film opens this Friday. Fans of westerns and suspense films are advised to make the trip to Red Hill.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/9vafKLgdg94" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Queue Tip: Halloween has come and gone but a good ghost story can be enjoyed at any time. And The Eclipse, on DVD and Blu-ray, is a good ghost story, from Irish playwright and filmmaker Conor McPherson. The best ones are more about the living than the dead, and The Eclipse introduces us to Michael (the excellent CiarÁ¡n Hinds), who is struggling to raise his two children and start a writing career in the shadow of his wife’s death. The fog lifts when a writer’s conference in his picturesque seacoast town brings him into contact with noted horror author Lena (High Fidelity co-star Iben Hjejle)—but this intensifies his ongoing bout with bad vibes and after-midnight heebie jeebies. Further complicating his emotional well-being is the growing instability of his father-in-law Malachy (Jim Norton), who has been placed in a rest home, and the arrival at the conference of the haughtily successful Nicholas (Aidan Quinn), who, besides a film deal with the ”lovely” Ralph Fiennes, has a yen for Lena.

Onstage, McPherson specialized in spooky monologues; one of his best, St. Nicholas, has been revived at New York’s Irish Repertory Theatre, with Joe Martello as a drama critic tangling with vampires. He had trouble getting his characters to converse, however, until his delightful breakthrough The Seafarer, which was performed on Broadway in the 2007-2008 season. In the show, Hinds played a satanic cardsharp, and Norton one of his wily marks. Not yet 40, McPherson, who received Tony nominations for writing and directing The Seafarer, has directed two other theatrical films, neither released here, so The Eclipse is something of a debut. (You may have run across the first film he wrote, 1997’s funny, Tarantino-ish I Went Down, on cable.)

Onstage, McPherson specialized in spooky monologues; one of his best, St. Nicholas, has been revived at New York’s Irish Repertory Theatre, with Joe Martello as a drama critic tangling with vampires. He had trouble getting his characters to converse, however, until his delightful breakthrough The Seafarer, which was performed on Broadway in the 2007-2008 season. In the show, Hinds played a satanic cardsharp, and Norton one of his wily marks. Not yet 40, McPherson, who received Tony nominations for writing and directing The Seafarer, has directed two other theatrical films, neither released here, so The Eclipse is something of a debut. (You may have run across the first film he wrote, 1997’s funny, Tarantino-ish I Went Down, on cable.)

What an assured ”debut” it is, too, from a story and co-screenplay by Billy Roche, with the key elements in near-perfect balance. Hinds’ taciturn, touching performance bounces off nicely on Quinn’s atypically sarcastic, self-loathing portrayal (a clumsy, absurd fight scene is a highlight), and he and Norton (a Tony winner for The Seafarer) transfer their stage chemistry to the screen in a much different scenario. Accompanied by a lovely score by Fionnuala NÁ ChiosÁ¡in themes of transcendence through love and art are briskly developed in its 88 minutes—oh, and there are several good scares, including at least one leap-off-your-couch moment. A good ghost story has to have those, too.

Two par-for-the-course making-of’s supplement the DVD transfer, a fine 2:1 aspect ratio encoding. It took some time for The Eclipse to come out from under the shadow of numerous other titles on my pile, and it’s worth hauling up from yours.

Fond Farewell: To George Hickenlooper, gone too soon. I’ve interviewed a number of filmmakers over the years but never got to know them; I never interviewed the director of the short Some Call it a Sling Blade (from which Billy Bob Thornton’s indie hit came), Mayor of the Sunset Strip, Factory Girl, or the forthcoming Casino Jack, but did get to know him through his informative and reasoned posts on the Hollywood Elsewhere site, which always threw light onto the heated discussions there. RIP to a voice stilled far too young.

Comments