At 11:29 A.M. on Friday, July 8, 2011, just three months past the 30th anniversary of the first shuttle launch, the Space Shuttle Atlantis launched into orbit for the last time, thus beginning the final mission of the Shuttle program. It was a breathtaking, gorgeous launch — one which came very close to being scrubbed due to weather. And it was one of the most bittersweet moments of my 33 years.

If you know me at all, you know that I am a giant space nerd. I’ve been one for as long as I can remember, and it’s mostly due to NASA and the Space Shuttle. I remember watching Shuttle launches as a little girl and being fascinated by the idea that humans were going into space on what looked like an airplane. And I wanted to know when I could go up, too. As it turns out, I could never be an astronaut, for many reasons I won’t go into, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t still love the space program, and in particular, the Shuttle program.

I wasn’t alive during the height of the space race in the ’60s, nor was I around for any of the Apollo missions. But I have been alive for the entirety of the Shuttle program and watching the beginning of its end yesterday made me sadder than I thought possible. I regret that I never got to see a Shuttle launch in person, though I did get to take an incredible tour of Johnson Space Center a few years ago that will always be one of the most memorable days of my life. I wish that more people had paid as much attention to the Shuttle program in the last couple of decades as they did in the first. It would be great if we could equally take for granted space exploration and still be fascinated by it.

I’ve been hearing from a variety of sources, including NASA itself, that the end of Shuttle is making way for a new chapter for the U.S. space program, and I do believe that we are capable of great things in the future. But the Shuttle program has been a huge part of my life, so I’m very emotional about its end. Though, I’m guessing not as emotional as these guys:

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/ldlphfRuk1Q" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Now that the Shuttle program is coming to a close, I hope that it can get as much attention in the pop culture world as the Gemini and Apollo programs have received. Maybe Tom Hanks will see fit to give us a mini-series about the Shuttle that’s as brilliant as From the Earth to the Moon (1998). Or maybe we’ll see a feature film that looks at the Shuttle program and its history, much like The Right Stuff did for the early U.S. space program (and yes, I know that was a book first). I would love to see more quality films that celebrate the Shuttle rather than overlook it for the shinier, uninvented spacecraft of the future.

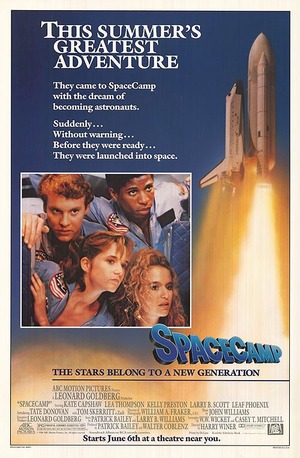

One film that does embrace the Shuttle program, even if that embrace is slightly spaghetti-armed, is SpaceCamp (1986). I saw this movie in the theater when I was was eight years old and I adored it, despite the fact that it was released just five months after the Challenger disaster, which I was still traumatized by (that disaster also doomed the film to do terribly at the box office — the rest of the world was also still traumatized, I guess).

The movie tells the tale of a group of kids — aspiring astronaut Kathryn (Lea Thompson); slacker Kevin (Tate Donovan); science lover Rudy (Larry B. Scott); smart Valley Girl Tish (Kelly Preston) and Star Wars lover Max (Joaquin Phoenix) — who spend the summer at Space Camp and, along with their astronaut instructor, Andie (Kate Capshaw) get acidentally launched into space aboard Shuttle Atlantis.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/BYCJAkeD33o" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

At the time, though I loved the Space Shuttle, I didn’t really know much about how it worked. So, when I watched this movie, I totally bought it hook, line and sinker. OF COURSE they let a bunch of kids sit inside a brand new Shuttle while they tested its engines for the very first time. OF COURSE the Shuttle could be “accidentally” launched into space by an annoying robot. Hell, I even believed that they shot the space scenes in zero gravity. Give me a break — I was eight.

Now that I’m older and wiser, having learned a great deal more about the Shuttle program, it’s very hard for me to watch this movie with a suspension of disbelief. There really is so much they get wrong that it’s almost painful. But first, let’s talk about some of what they got right:

- In the summer of ’85, when this movie was filmed and, presumably, set, Shuttle Atlantis had not yet made its maiden voyage. And its FRF (flight readiness firing) did happen at the tail end of the summer — early September, to be exact.

- Space Camp does exist — it’s located in Huntsville, Alabama, near the Marshall Space Flight Center. The movie was partially filmed there. Most of the activities you see during the training scenes would have been activities the campers would have likely engaged in at Space Camp.

- The Shuttle launch and landing footage was real — the launch footage came from STS-51-C (Discovery) and the landing footage came from STS-8 (Challenger).

- Upon meeting Andie, Kathryn remarks that she was the “back-up pilot for the first Discovery mission, but Coats got it instead.” Michael Coats was indeed the pilot for STS-41D, which was Discovery‘s maiden voyage, launched August 30, 1984. Interestingly, this was the first spaceflight for a female astronaut, Judith Resnick, who was one of the astronauts killed in the Challenger disaster.

- When asked by Andie why she came to Space Camp, Tish replies, “Well, I did this audit at JPL in radio astronomy. It was unbelievable.” The JPL Tish speaks of is the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It’s very possible she could’ve sat in on a lecture series of some sort given there about radio astronomy.

- The campers miss their landing window at Edwards Airforce Base, which was, for a time, the only landing facility for Shuttle — before they made Kennedy Space Center a launch and landing site. They begin discussing other possible landing sites and Kathryn brings up White Sands, New Mexico. She says that “Columbia of ’82 landed there” because of a big emergency. She’s talking about STS-3, which was Columbia‘s third mission. It was planned as a 7-day flight, but the mission was extended one day because of high winds at the backup landing site: Northrop Strip, White Sands, New Mexico. The Shuttle couldn’t land at Edwards because it had flooded after heavy rain.

Sadly, those are probably the most accurate things about the movie. I’m not going to list everything the filmmakers got wrong, or just plain made up, because I don’t want to be a total bummer, but here are some of the big ones:

- In the film, Space Camp seems to be very near Kennedy Space Center in Florida, since it’s only a short car ride to get to the launch pad. As I mentioned, though, Space Camp is in Huntsville, Alabama, which is actually about 700 miles away from Kennedy.

- In order to launch the Shuttle into space, Jinx the robot initiates a “thermal curtain failure,” which supposedly meant that one of the SRB’s overheated, so they have to ignite the other one in order to launch the Shuttle and preventing disaster. However, if the SRB wasn’t really overheating — if Jinx just made it look like it was — igniting the other SRB wouldn’t launch the Shuttle safely. It would actually have caused the it to lift off and crash, which is what they were trying to avoid in the first place.

- As they are climbing into orbit, Andie tells Kevin that he has to hit the switches to initiate SRB and ET separation. In reality, these functions are done by the Shuttle’s onboard computer — neither the pilot nor commander touch anything to make these actions happen.

- In the film, Mission Control is handled entirely at Kennedy Space Center. Really, though, after the Shuttle launches, Kennedy has no more contact — communications are immediately taken over by Mission Control at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Also, there really is no such thing as short-range radio communications with the Shuttle. The communication system used during FRF would be the same as for standard missions, so the crew would not have lost contact with Mission Control once they reached a certain distance from the launch site.

- Once they’re on orbit, zero gravity only seems to affect some things — their bodies, Tish’s earrings, some equipment — and their hair is not affected at all. But if you’re in zero gravity, and you have even slightly long hair, it would float just like everything else.

- They don’t open the Shuttle’s cargo bay doors until it’s time for the space walk. In reality, the Shuttle opens its cargo bay doors almost immediately after it’s in orbit so that heat is able to vent through radiators built into the doors. If the bay doors remained closed for as long as they do in the film, the vehicle would likely overheat.

- One tank of oxygen is supposed to last four hours. The display shows the capability for four tanks. So, if they had four tanks, the shuttle would only have a two-day supply. By that point, though, missions were lasting way longer than that — most of them between 4-7 days.

- Daedalus was a totally fictional space station. The name pays homage to Project Daedalus, which was was a study conducted between 1973 and 1978 by the British Interplanetary Society to design a plausible interstellar unmanned spacecraft.

- When Max starts floating away from Daedalus, he goes really fast and it looks like he’s about ready to crash into the moon. Using the MMU — or jet pack, for you non-techies — Andie gets to him pretty quickly. The physics of all this seems really off. And, the moon likely wouldn’t have looked THAT big.Take a look:

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/opdDHA8dy1k" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

- After the automatic re-entry is aborted in order to save Andie, it’s stated that there isn’t enough oxygen, even with the replenishment, to make the next landing window at Edwards. By then, though, the shuttle landing facility at Kennedy was in use and landing there would’ve been the first option available to them. Edwards would’ve been the back-up. And, generally, if the first window to land at a site is missed, there’s usually another one available in about 90 minutes, so they would’ve had plenty of time and oxygen to land without immediately switching to a back-up site.

One thing that isn’t really an innacuracy, but that I find to be interesting is the exchange between Kathryn and Andie when Kathryn states that she thinks being a commander is more important than being a pilot. In the Shuttle program, at the time, before you can be a commander, you have to be a pilot. And Kathryn acts like she doesn’t know that one job is a stepping stone to the other. I can understand why she’d want to jump right to the commander position, but for someone who is as knowledgeable about the space program as she is, she would at least acknowledge that Pilot is a really important position and that she wouldn’t get to be Commander unless she was Pilot first.

Coincidentally, NASA wouldn’t see its first female Shuttle commander until 2005, when Eileen Collins became the commander of STS-114, which was the Shuttle’s return-to-flight mission after the 2003 Columbia disaster. There would be another female Shuttle commander, Pamela Melroy, who would command STS-120 two years later. Incidentally, both of these women commanded Discovery, which is the Shuttle for which Kathryn notes that Andie was the back-up pilot.

After all this blathering on, I suppose I should talk about the film’s soundtrack, right? Appropriately, since Max is a huge Star Wars nerd, the score was done by the one-and-only John Williams. It’s a fantastic, quite patriotic-sounding score that is befitting of a film about the Space Shuttle. I dare you to listen to title piece and not feel like you’re getting ready to be launched into space (coincidentally, that piece also reminds me quite a bit of the modern Olympics theme, which Williams also composed). I can’t help but be happy when I listen to this score — it’s one of my favorites of Williams’s and one that I think gets overlooked in his ouevre.

In addition to the Williams score, there were a few vocal tracks used in the film, though those did not show up on the official soundtrack album. Those include “Forever Man” by Eric Clapton, two Dire Straits songs and three songs by Joseph Williams, who, if I’m not mistaken, was the lead singer of Toto at the time this film was released and who also happens to be John Williams’s son. Of the younger Williams’s contributions, I was able to find two.

Score by John Williams:

Main Title

Training Montage

The Shuttle

The Computer Room

Friends Forever

SpaceCamp

In Orbit

Viewing Daedalus

Max Breaks Loose

Andie Is Stranded

Max Finds Courage

White Sands

Re-Entry

Home Again

Eric Clapton – Forever Man

Joseph Williams and Paul Gordon – Turn It Up

Dire Straits – So Far Away

Dire Straits – Walk of Life

Joseph Williams – Don’t Look Back

If you’ve managed to read — and enjoy — this entire, epic post, I thank you. Even though SpaceCamp isn’t a very good movie, it’s one that means a lot to me because of the era of the U.S. space program that it represents. I’m glad it exists and I hope that future generations will watch it with the same awe and wonder I did when I was a kid — you know, before they realize how terribly inaccurate it is — and will take an interest in the Shuttle program that was so important to me and many other people of my generation.

So long, Shuttle. I’m going to miss you terribly.

Comments