Like many cinephiles, I am obsessed with lost/alternate cuts of films. It presents an alternate version of history and, for me, was one of the main draws to a film’s home video release.

Usually, discussions of alternate cuts revolve around which version you should see if you have never seen it before. But lately, for some reason, a lot of people have found themselves stuck at home and wondering what to do to pass the time.

This gives me a valuable opportunity to explore multiple versions of films. (Hey, is it really that much worse than watching Tiger King?) I wanted to see not which one was the most ”definitive,” but rather whether the different versions had any merit. Films can be made from scratch in the editing room and you can have a great script and great scenes that are destroyed by a poor edit.

For a while there was a rush to get ”director’s cuts” out even today people are obsessing over an alternate version of The Justice League being added to WarnerMedia’s new streaming service. While it is important to ensure a filmmaker’s vision ends up on screen, taking a look at other cuts helps me determine if the underlying material was strong enough to begin with.

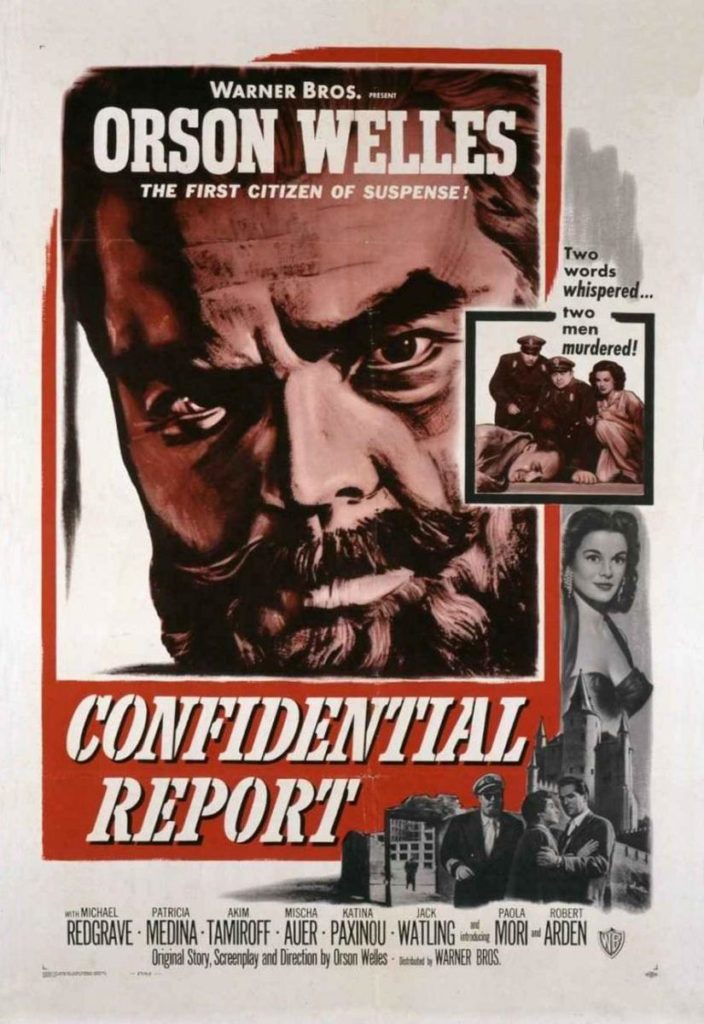

With that in mind, today I’m taking a look at one of the most infamous victims of editing in film history — Orson Welles. And I’m looking at a film that has been long overlooked in his filmography Mr. Arkadin aka Confidential Report. It’s a movie about a wealthy businessman trying to erase his mysterious past and was made at a time when Welles had already been dismissed by Hollywood as a one hit wonder who made films the public had no interest in. He couldn’t even maintain control over his European productions and Arkadin, although released in theaters, was never properly finished in his lifetime. There are five different cuts floating around, but three of them deserve closer examination.

The Movie:

Mr. Arkadin, isn’t Orson Welles’ worst movie, but it may very well be his strangest. Welles constantly struggled for a box office success throughout his career. After his starring role in The Third Man, Welles realized he had struck gold. People loved Harry Lime and the struggling Welles was eager to capitalize on that connection with the audience. First, Welles starred in a radio show that further explored Harry Lime’s adventures. Then he used that show as a basis for his first directorial outing in four years.

But while Carol Reed’s masterpiece captured a Europe still recovering from World War II and still in a state of flux, Arkadin depicts a world that never really existed. There are a few references to the then then current geopolitical situation, but most of the movie plays like a prewar travelogue. Welles maintained a romantic view of the world throughout his life and was passionate about learning as much as he could about European nations that had existed for millennia before the U.S. This helped him in his early career, but he never responded or acknowledged anything that happened in Europe since the beginning of WWII. His unfinished Don Quixote was a love letter to Spanish culture that was produced while the country was still controlled by a fascist regime. Most of his independent works were Shakespearean adaptations, filmed in ways that are indistinguishable from the stage adaptations he starred in as a young man. Another unfinished work, One Man Band, paints an old-fashioned version of London without addressing why the city had gained a reputation as ”swinging London.” (Welles’s incomprehensible use of ”yellowface” in the film adds icing to the cake made up of his outdated sentiments.)

This movie is a culmination of Welles’s lifelong obsessions. He was deeply interested in how the rich and famous were still dissatisfied with their position in life. He was influenced by film noir and classic Hollywood genres. And he wanted to make his films as epic as possible, even on a limited budget. Jumping from country to country gives the sense of a massive production, even when Welles didn’t have the money to properly convey his epic vision.

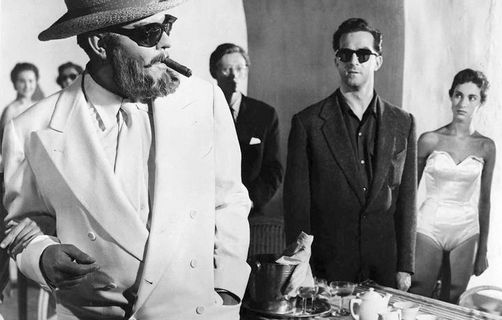

The plot also lends to a globe hopping character. A smuggler named Van Stratten (Robert Arden in a much-criticized performance) is hired by the billionaire Gregory Arkadin (Welles) to investigate his past. He claims to have no memory before finding himself in Poland in 1927. Naturally, the assignment is a ruse so Arkadin can locate his former associates and kill them so his daughter (Paolo Mori) doesn’t find out the truth about him. Van Stratten is desperately trying to save the last person who knows about Arkadin’s criminal past, Jacob Zouk (Akim Tamaroff). (The framing device has van Stratten explaining to the old man the events that lead up to him tracking Zouk down.)

It’s obvious what’s happening from the first encounter with Arkadin. There is no ambiguity and his request is farcical. Would you believe Jeff Bezos if he claimed not to remember anything about his life before 1985? The framing device is an excuse for Welles to engage in his true desires — making his own noir based on one of his most famous characters.

As weird as the plot is, the film is very engaging. Arkadin is an appropriately imposing figure and Welles made me believe his character could do anything he wanted. And Van Stratten’s realization of his true purpose is intriguing. And the (in)famous gourmand Welles manages to incorporate a food subplot. The former Arkadin friend Jacob Zouk is obsessed with obtaining a goose liver on Christmas Eve, and van Stratten is tasked with finding one.

Even if it’s not as good as Touch of Evil — or most of Welles’s other films — it’s never boring. We’re entertained by some great character actor performances, including a hammy turn by Michael Redgrave as a junk shop owner and Mishca Auer as the owner of a flea circus who provides one of the film’s best visuals. Film critic Phil Hall called Arkadin a ”brilliantly terrible movie…it is difficult not to be entertained by it.” Even though I don’t agree with his conclusion that this is one of the worst movies of all time, it’s hard to disagree that the movie isn’t entertaining. The performances alone make the film one of Wellles’ most memorable and, even if it’s a copy of much better films, Arkadin is still a great exploration into Welles’s obsessions.

Confidential Report

Welles completed filming but was not allowed to create his final cut. Instead, the first version eschewed Welles nonlinear structure with a straightforward narrative that really shows how weak the underlying story is. Although the framing device is the same — van Stratten finds Zouk and tells his story — we get extraordinarily little narration and we never see Zouk and van Stratten again until the final act of the film.

This was a mistake as the story was never the most interesting aspect of Arkadin. The film’s success is based on the visuals and the globetrotting adventures of the characters. Telling the story linearly does not emphasize those as much as the other cuts. Still, other reviewers have suggested this cut is the absolute worst of the bunch and the end result is sloppy and rushed.

I disagree — partly because there’s another cut with TERRIBLE editing, but also because I don’t believe this version makes the story more difficult to follow. Indeed, this is probably the most audience friendly version of the material and is one of the last classic ”noirs” before the genre died out completely. (Ironically thanks to Welles’s Touch of Evil, which subverted and deconstructed many classic noir tropes.) Welles was interested in the very act of filming and editing as a way of telling a story. The Confidential Report version ignores all of Welles’s techniques, and it’s hard to argue the results take a lot of the charm out of the movie. But to claim it’s as much of a hackneyed job as, say, how The Magnificent Ambersons was sliced up is a touch disingenuous. Besides, the film does keep Welles’s obsessions with Europe and the deep scars that never fully healed after two world wars, which was the entire point of the film.

Corinth Cut

Seven years after its release in Europe, Arkadin was finally released in America with a version that was allegedly closer to what Welles intended. Of course, this still isn’t quite the case, but the film does retain the important flashback structure Welles wanted. This automatically makes it an important cut to watch.

It’s a shame the film itself looks terrible, with so much of the gothic imagery rendered impotent by poor editing, a bad soundtrack, and a surviving print that’s clearly not in good condition. It ruined a lot of the experience for me. I was too distracted by editing mistakes that looked like something a person unfamiliar with iMovies would make.

One aspect that was improved upon is van Stratten’s narration. While only a few lines are retained in Confidential Report, this version restores much his dialogue. It’s missing a lot of the cuts back to van Stratten in Zouk’s apartment as he’s narrating his story, but they do keep the flashbacks.

This helps emphasize the global trek that van Stratten must take and just how influential Arkadin is in the world. He can find anyone anywhere and shows up seemingly at random. When the story is told linearly, this element is lost because we expect Arkadin to show up where he shows up in the story. In the flashback structure, he remains an enigmatic and we wonder how he can be influencing so many events across the world.

Also, the structure emphasizes how much of a weasel van Stratten is. In the Confidential Report he’s a more straightforward noir protagonist. The flashback structure emphasizes how much he is trying to be a manipulator in the same vein as Arkadin and how he only cares for himself. As he tells the story, it’s clear that he’s not interested in stopping a villain or informing anyone of Arkadin’s crimes. (Zouk is firmly aware of Arkadin’s past, so there is no sense in relaying this information to him.) Rather, he is telling the story to get audience on his side. He does feel upset when he finds out a former associate has been killed but before long he’s only interested in saving himself. He doesn’t even have the moral anchor Arkadin has with his daughter.

The Corinth Version shows how Welles could take weaker material derived from his more famous successes and create something interesting.

Comprehensive Version

The Comprehensive Version of Arkadin was compiled and released by the Criterion Collection in 2006. It supposedly is the closest version to match what Welles intended — at least, that’s how other reviewers have categorized it. Yet what it actually does is compile all the completed footage Welles shot into one cut. Whether or not any of this would have been deleted from a final version is debatable and the fact it runs six or seven minutes longer than the previous two versions is telling. It was released at the height of the ”director’s cuts” on home video obsession, so this feels like it should be the version Welles intended to be released.

Taken on those terms, the ”Comprehensive Version” is a fascinating experiment. It presents all the narration intended for the narrative structure, it includes an extended ending, and there is a lot more b-roll footage that helps establish the scenes. Only a few scenes are properly extended (including the final scene of van Stratten talking to Arkadin’s daughter) but this cut is the best at establishing its settings and emphasizing van Stratten’s trips around the globe.

But even if this is the most complete version of the film, I’m not sure if it’s the best. For one, the plot doesn’t lend to a lengthy runtime and the cuts over 90 minutes were already straining the material. The new footage doesn’t add any new twists to the plot (although I do prefer the ending here with its crashing plane as well as the cuts back to Zouk’s apartment). It’s just padding — the sort of padding good editors know to excise. We get padded shots of the Spanish procession and further establishing shots of the masquerade…but it all doesn’t tell us anything new.

For another, as I said, the film was already strained and adding more to it makes it tedious. There’s a lack of suspense to this version and the visual restoration threatens to derail the image of Arkadin. The flaws in Welles’s makeup are extremely visible and the extra padding makes Arkadin not seem like a gamemaster fully in control of the situation (until the end, anyway) but puts the focus back again on van Stratten’s travels around Europe. This padding makes the trip seem more chaotic for both van Stratten and Arkadin which takes away from Arkadin’s menace.

I’m glad this version exists, and we finally do have a good looking restored version that arguably follows Welles’s intentions. But honestly, I think the Corinth Cut is the best version for newcomers. Not only was that the only version personally touched by Welles, but it is the most effective at establishing who Welles wanted Arkadin to be and what he hoped to accomplish by telling his story. Unfortunately, once again, Welles was cheated of the opportunity.

Comments