“Do you like one-person shows?” I was asked before I became an awards nominator for the Drama Desk a few years back. Well, sure; Christopher Plummer as John Barrymore (Barrymore), Mary Louise Wilson as Diana Vreeland (Full Gallop), and Sian Phillips as Marlene Dietrich (Marlene) came to mind. But it was not an idle question. I saw nearly 300 shows a year from across the New York theatrical spectrum in the 2007-2008 season, and I figure about 15-20% were one-person shows. Which meant a lot of nights in the company of solo performers telling their stories, riffing on politics, or, more often than not, putting on wigs and costumes and makeup and playing other people.

“Do you like one-person shows?” I was asked before I became an awards nominator for the Drama Desk a few years back. Well, sure; Christopher Plummer as John Barrymore (Barrymore), Mary Louise Wilson as Diana Vreeland (Full Gallop), and Sian Phillips as Marlene Dietrich (Marlene) came to mind. But it was not an idle question. I saw nearly 300 shows a year from across the New York theatrical spectrum in the 2007-2008 season, and I figure about 15-20% were one-person shows. Which meant a lot of nights in the company of solo performers telling their stories, riffing on politics, or, more often than not, putting on wigs and costumes and makeup and playing other people.

Some of them were good. (The winner that year was Laurence Fishburne, folksy and commanding, in Thurgood, which was later filmed for HBO.) That immersion, however, made me reluctant to enter the waters too deeply again. The bio-shows, in particular, tend to stick to a familiar template, and I need a good reason to go.

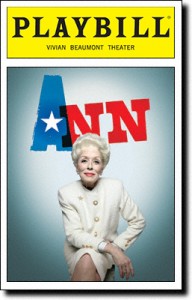

Holland Taylor is one. Best known for playing sardonic society dames or other lovably overbearing types, as on Two and a Half Men, the 70-year-old actress wrote Ann for herself, and with the help of some deft costuming (Julie Weiss) and all-important “Republican hair” (wigmaker extraordinaire Paul Huntley) she becomes Ann Richards, one-term Texas governor and lifelong Democratic firebrand, for two hours. Two pleasant hours, I hasten to add, at the Vivian Beaumont at Lincoln Center, though Taylor is rather too cautious with her subject.

The first-time playwright sticks to the script, as it were. In the time-honored tradition of solo bio-shows, we begin with an address, with Richards at “the school auditorium at an imaginary college in the middle of Texas.” We then go back in time, to the governor’s office in Texas, circa 1993, where we observe her in the tried-and-true moment of crisis–Richards ponders staying the execution of a reprehensible rapist/murderer, something Texas governors are loath to do. As Richards works the phones to reporters, associates, and family members, in a telephonic tour-de-force for Taylor (a genuine Texas rose, Julie White, voices her unseen secretary), we go over the cornerstone events of her life to date, including alcoholism, divorce, and the call to service that put her on the path of politics, which led to her legendary keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in 1988, when she was state treasurer. Names are dropped: Barbara Jordan, Bill and Hill (who were at the show last week). Wisdom is imparted: The government isn’t them, it’s us, we shouldn’t be afraid to serve, women should be empowered. There is a final, inspirational summation, post-career, post-life, even (Richards, who spent her last years in New York, died of cancer in 2006, at age 73).

Directed by Benjamin Endsley Klein, Ann is often tart and funny, like its subject, and the Philadelphia-born Taylor clearly enjoys losing herself in her rootin-tootinness. It’s also kind of shapeless within its framework, and it doesn’t really survive its intermission, the bane of all one-person shows. It’s hard to get the audience’s attention a second time, harder still when the story runs out of momentum, as Richards’ does once we leave the governor’s mansion. The last twenty minutes is all uplift and platitudes, and that’s a lot of uplift and platitudes. Taylor avoids conflict (the decision about the stay is tossed off in a single line) and score-settling, to the point where the famous keynote line about vice president George Bush’s being born with “a silver foot in his mouth” is omitted from the projected recreation that begins the show. Indeed, neither Bush is mentioned in the play at all, which is like cutting Ronald Reagan out of a show called Tip.

Directed by Benjamin Endsley Klein, Ann is often tart and funny, like its subject, and the Philadelphia-born Taylor clearly enjoys losing herself in her rootin-tootinness. It’s also kind of shapeless within its framework, and it doesn’t really survive its intermission, the bane of all one-person shows. It’s hard to get the audience’s attention a second time, harder still when the story runs out of momentum, as Richards’ does once we leave the governor’s mansion. The last twenty minutes is all uplift and platitudes, and that’s a lot of uplift and platitudes. Taylor avoids conflict (the decision about the stay is tossed off in a single line) and score-settling, to the point where the famous keynote line about vice president George Bush’s being born with “a silver foot in his mouth” is omitted from the projected recreation that begins the show. Indeed, neither Bush is mentioned in the play at all, which is like cutting Ronald Reagan out of a show called Tip.

Maybe it’s easier to create one of these bio-shows when the subject is long gone and no one will turn up at the theatre with a grievance. In any case Ann preaches to the converted, as so many of these shows do, and if you’d like to bask in the reflected glory of one of the left’s bawdier saints have at it. My mother-in-law would love the play. But I wonder how true a portrait Richards would find it, beyond the hair.

Comments