The summer movie season may have ended but the indie phenomenon that is Boyhood continues. Richard Linklater’s 12-years-in-the-making portrait of a Houston youth, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), from age six to his freshman year at college. Critics greeted it with near-universal hosannas, and count me in as one of its admirers. But a certain amount of grumbling could also be detected–and when my almost-from-boyhood pal and Popdose colleague Jon Cummings went thumbs down, I knew it was time to hash it out. So here it goes, with me offering my positive take (with reservations) and Jon–well, long time, no see, buddy, and if you’re gonna thrash a little kid like this, come back into the arena and pick on some grownup targets, OK? Missed ya.

The summer movie season may have ended but the indie phenomenon that is Boyhood continues. Richard Linklater’s 12-years-in-the-making portrait of a Houston youth, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), from age six to his freshman year at college. Critics greeted it with near-universal hosannas, and count me in as one of its admirers. But a certain amount of grumbling could also be detected–and when my almost-from-boyhood pal and Popdose colleague Jon Cummings went thumbs down, I knew it was time to hash it out. So here it goes, with me offering my positive take (with reservations) and Jon–well, long time, no see, buddy, and if you’re gonna thrash a little kid like this, come back into the arena and pick on some grownup targets, OK? Missed ya.

(Spoilers ahead.)

JC: The hype over Boyhood has been cacophonous, hasn’t it? Between the various celebrations of the filming process, the improvised plotting and dialogue–and the suggestions that we already had our Oscar winner in August–the film jumped to the top of the must-see list for hipster-doofuses everywhere.

BC: The “masterpiece” label hung on it does it no favors. That’s tough to live up to when you enter the theater expecting to be enthralled, enraptured, etc. Few movies do that; Richard Linklater’s sure don’t. He’s gotten a couple of Oscar nominations for writing but prestige isn’t his thing. Nor is crowdpleasing, School of Rock excepted. He’s an indie guy through and through, and as he’s in his mid-50s, with a 25-year career behind him, I don’t expect to see him putting out Academy Awards bait. If it happens to Boyhood, it’s not because he consciously thought about it 12 years ago.

I write a Top 10 list every year; once filed, truth be told, I rarely revisit them. In looking back I was surprised to see how many of Linklater’s films made it, or fell just outside of the yearly “pantheon.” He’s a major filmmaker who works unobtrusively, in miniature. I can see, say, Terrence Malick slapping his forehead in frustration when Boyhood was unveiled, as if an idea he should have had was realized by someone else, another Texan no less. But Mr. Tree of Life would still be shooting it, and the results would have been diffuse, pretentious.

In a sense, Boyhood is nothing new. Other movies have followed lives over long periods of time. Michael Apted’s Up documentaries began with seven-year-old subjects in 1964, with 56 Up premiering in 2012. (Coltrane was seven when filming started.) Harry Potter, referenced in Boyhood, led to eight films over ten years that took their leads from age 11 to 21. Boyhood with Quidditch!

In a sense, Boyhood is nothing new. Other movies have followed lives over long periods of time. Michael Apted’s Up documentaries began with seven-year-old subjects in 1964, with 56 Up premiering in 2012. (Coltrane was seven when filming started.) Harry Potter, referenced in Boyhood, led to eight films over ten years that took their leads from age 11 to 21. Boyhood with Quidditch!

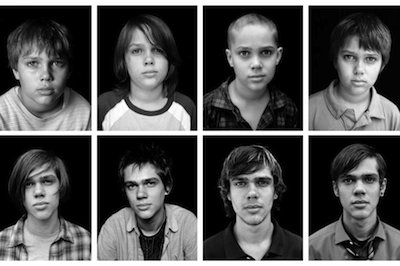

Boyhood minus wizards is a series of snapshots. I love that there are no title cards or obvious dissolves between years; you get the passage of time from the physiological changes, the clothes, and the hairstyles, sometimes unfortunate (age 10 and 11, rough, as I recall). Time is really Linklater’s subject; Boyhood compresses the decade-long gap between his Ethan Hawke/Julie Delpy films, removing backstory in the process. It’s up to you to fill it in as the movie goes from year to year–you, the hipster-doofus who grew up on Slacker and Dazed and Confused, then grew into marriage, children, the whole ball of wax that Boyhood looks at. Linklater, commendably, has aged with his audience.

JC: But just as I didn’t share in the general adoration for Before Midnight last year, finding its situations (and the characters’ reactions to those situations) completely unconvincing, I was unmoved by Boyhood and its ponderous (when not half-baked) exploration of a kid’s coming of age. For starters, the experience of watching my own son grow up over the past 17 years has seemed to move more quickly than Boyhood did during its nearly three-hour running time.

BC: Funny but I rarely thought of my own kids during the movie, maybe because they’re both younger than Mason. But, hey, all parents doze through a few years of their kids’ lives. You can revisit Mason’s on DVD and Blu-ray in a few months.

Seriously, though, Linklater made it a point to avoid the sort of obvious crisis situations that give most movies their drive. His own daughter Lorelei, cast in the movie as the lead’s sister, begged to be killed off during shooting–a real grabber!–but he refused. Before Midnight hinges on the characters trying to ward off a certain stasis that’s enveloped them; many people simply go into ennui, not taking inventory. His terrain in these films is the in-between moments before and after turning points. There’s no catharsis. That this movie is set in parched East Texas supports this mode; not to condescend (which Linklater never does) but you don’t get a sense of much happening within these communities, and when it does, you can sort of see it being dealt with and shrugged off till the next development. (But things do happen–elections. Moves. Jobs. Bad husbands. Harry Potter.) I find Boyhood‘s lack of drama, its anti-drama, compelling in its own right. And also problematic. And you’re about to come to why…

JC: I found Mason’s relationship with his mother woefully underdeveloped, relying on the imposition of simplistic monster-stepdads to move the plot forward. And even Mason and mom’s encounters with those monsters provided no real insights into either mom’s character or Mason’s eventual persona–not that Patricia Arquette seemed really capable of rising to the film’s acting challenges in any case.

JC: I found Mason’s relationship with his mother woefully underdeveloped, relying on the imposition of simplistic monster-stepdads to move the plot forward. And even Mason and mom’s encounters with those monsters provided no real insights into either mom’s character or Mason’s eventual persona–not that Patricia Arquette seemed really capable of rising to the film’s acting challenges in any case.

BC: I have a tortured relationship with Patricia Arquette. Loved her from True Romance (1993) to Flirting with Disaster (1996). But she got very mannered, very quickly; she didn’t have many dimensions to fall back on, actingwise, and she grated. I was glad to lose her to TV and Medium for several years.

She returned to my good graces here. Externally, she and Hawke (and Delpy) get a lot of points for letting themselves age naturally; obvious “star” work would kill the movies dead. I doubt Hawke has any problems becoming Nick Nolte, Jr., before our eyes, but for actresses such exposure can stop a career. Arquette looks every bit her age (46) and weight, the basis for creating a believably frazzled single parent, who’s never more alone that when she’s married. Her children are her island–and they’re frequently marooned for those 12 years. She makes bad choices. Fine, people do. (You wonder if Hawke’s character had a drinking or substance problem, too, but again, backstory.) What doesn’t click is that the kids don’t suffer for them; they bounce back without the changes really disrupting the film, and I don’t think that works, either. There are repercussions–the film’s most agonizing scene is when her kids ask if they’ll ever see Husband No. 2’s children again when they flee in their car, a question that goes unanswered. Life otherwise rolls on too easily, or seems to. Perhaps the undercurrent of those unfulfilling marriages explains the film’s relative lack of humor and sentiment.

Still I think she’s the movie’s great success. I felt for her character. She’s not a loser–amidst contradictions and poor decisions she keeps her family going and acquires a decent career. Which, that said, leads to the movie’s worst scene, where the day laborer she inspires thanks her for taking an interest years later. It’s poorly written and very badly acted; I assume Linklater decided to forego better supporting players to a) give the movie its location-based realism and b) ensure that the actors he did hire would be easily available. It’s an awkward sequence, more awkward than such an encounter would be in real life. But its placement is interesting. To give the mother a happy ending it would be her last scene in a different movie; in this one, it’s her second-to-last, with the last being where her composure slips, revealing resentment, fear, and frustration as boyhood and Boyhood end. And I think Arquette played it beautifully.

JC: As for dad, played by Ethan Hawke…who has irritated me (with very few exceptions) pretty much whenever I’ve seen his too-angular mug over the last two decades, from Reality Bites forward…well, all I can say is that I gave up imposing profound life wisdom on my kids the first time they inserted their earbuds and tuned me out. You gotta sneak that shit in! You gotta ask your kids questions and force them to come up with their own answers, and help them figure things out for themselves. And you gotta slip those conversations in with the everyday reminders to clean their rooms and wipe their butts–not after driving six hours through an East Texas hellscape to throw rocks into a creek. If Ethan can make that sort of thing work for him in real life, more power to him. I don’t buy it.

JC: As for dad, played by Ethan Hawke…who has irritated me (with very few exceptions) pretty much whenever I’ve seen his too-angular mug over the last two decades, from Reality Bites forward…well, all I can say is that I gave up imposing profound life wisdom on my kids the first time they inserted their earbuds and tuned me out. You gotta sneak that shit in! You gotta ask your kids questions and force them to come up with their own answers, and help them figure things out for themselves. And you gotta slip those conversations in with the everyday reminders to clean their rooms and wipe their butts–not after driving six hours through an East Texas hellscape to throw rocks into a creek. If Ethan can make that sort of thing work for him in real life, more power to him. I don’t buy it.

BC: We have to assume that all we see of dad in the movie is all that his kids see of him in real life. He has to make those minutes, and those mixtapes, count. There’s a certain anxiety there, a trying-too-hard quality that I thought Hawke nailed. The kids see it, too; maybe they’re more willing to indulge him than a day to day parent who’s always, predictably around. It’s amusing that he marries a nice Christian woman (who, refreshingly, is presented in a non-stereotypically) who can keep him in line, unlike his first wife. He and Arquette play flawed, decent people who don’t add up as a married couple.

Maybe because I see Hawke onstage regularly I don’t have outstanding issues with him. He’s shown more variety there than he has in movies.

JC: Beyond the sheer chutzpah of picking out a first-grader at the turn of the millennium and trusting that he’d grow into a sloe-eyed, brooding Linklater hero, what in particular floated your boat about Boyhood?

BC: An outstanding if not altogether novel idea has become a good Richard Linklater film, if not necessarily a top-tier one. I’m still sorting it out; no “instant masterpiece” talk from me. Yet you’ve walked us over to the elephant in the room, what no one is talking about: I don’t think Ellar Coltrane, now 20, is as interesting as what’s going on around him. Linklater took a gamble on him, and I don’t think he lost; he’s as appealing as any kid when a child, and as mopey as any teen. But he doesn’t magnetize the screen. He’s sort of a Michael Sarrazin type, and if you have to look up Michael Sarrazin on the IMDb, well, there’s the problem. He’s perfectly ordinary, which is to say, perfect for what Linklater wanted. Yet I don’t see much range or depth there, even in the undercurrents. The strength of the film is that we see him mature in a way rarely seen; the limitation, given restrained drama or any over-fictionalization, is that he grows up to be, well, Richard Linklater. Which is probably healthier than growing up to be Michael Bay, if less fun. Maybe different kids can be assigned different directors and we can have a range of Boyhoods and Girlhoods in the coming decades.

BC: An outstanding if not altogether novel idea has become a good Richard Linklater film, if not necessarily a top-tier one. I’m still sorting it out; no “instant masterpiece” talk from me. Yet you’ve walked us over to the elephant in the room, what no one is talking about: I don’t think Ellar Coltrane, now 20, is as interesting as what’s going on around him. Linklater took a gamble on him, and I don’t think he lost; he’s as appealing as any kid when a child, and as mopey as any teen. But he doesn’t magnetize the screen. He’s sort of a Michael Sarrazin type, and if you have to look up Michael Sarrazin on the IMDb, well, there’s the problem. He’s perfectly ordinary, which is to say, perfect for what Linklater wanted. Yet I don’t see much range or depth there, even in the undercurrents. The strength of the film is that we see him mature in a way rarely seen; the limitation, given restrained drama or any over-fictionalization, is that he grows up to be, well, Richard Linklater. Which is probably healthier than growing up to be Michael Bay, if less fun. Maybe different kids can be assigned different directors and we can have a range of Boyhoods and Girlhoods in the coming decades.

JC: You certainly make some interesting points, but I don’t sense you changing my mind about (or causing me to feel more moved by) the film. We’re just going to have to agree to disagree on Arquette’s performance, for one thing. I suppose she picked up her game a bit (a bit!) over the last couple years of filming, as her character was finally allowed to blossom, but if we assume that much of this film was the result of Linklater, Arquette, Hawke and a few others brainstorming situations and then improvising the dialogue–because that’s the way they’ve described the process–then I just don’t feel like Arquette had her head in that process the way the others did. If you think back on the film, she simply disappears for much of the midsection. There was a point about halfway through when I thought, we haven’t seen mom much at all for a half hour!…even as Bad Stepdad (Marco Perella) shitty-acted his way toward his final status as an abusive drunk. (Perella seems to land a role in pretty much every film shot in Texas; I’m waiting for an explanation as to why.)

Considering that Mason lives with his mother throughout his boyhood, and dad is just an occasional player, it’s nonsensical (considering the film’s strained efforts at realism) that Hawke would get as much screen time as he does compared to Arquette. Yet, of course, his role is much more compelling, and his impact on Mason is portrayed as being much stronger than mom’s. Yet his role, as I said, is largely one of perpetually dropping in to offer sage advice, while Arquette’s is largely one of moving from house to house, bad relationship to bad relationship, lousy job to college to better job. Which is all fine–that’s what the Surface Stuff of parenthood is all about, I suppose, particularly for a broken family. But it’s also problematic, in a film called Boyhood, that the parents are the ones we see having most of the emotions and performing most of the action. Until Mason becomes a teenager, Coltrane is given little to do besides react to one adult or another. To use a 50-cent word, Mason isn’t given much “agency” in his own development, at least not until he’s a teenager. (I will say, though, that Coltrane’s eyebrows have a whole lot of agency through his middle-school years–I thought those suckers were going to slink right off his face through the film’s middle third, until his face finally grew into them.) I suppose the emphasis on the adult characters’ performances and actions is inevitable, this being a movie written and directed by adults, with adult stars, for an audience of adults. But that doesn’t make it a real representation of boyhood. Even a seven-year-old engages in activities, has intense feelings, and develops personality traits that eventually inform his character as a teen and beyond.

But we see precious little actual boyhood in Boyhood. We see a lot of parenthood–but if I want to see a film about parenthood, I can pull out a treasured DVD and watch Mary Steenburgen blow Steve Martin until he crashes his car. By the way, Martin and Steenburgen’s older son in that movie? Anxiety-ridden Kevin? He’s a much more well-rounded character than Mason turns out to be in Boyhood, at least until the film’s final moments. So are all the kids in Apted’s Up series, who–even when they were seven, much less 14–showed that even little kids can have real, compelling ideas and attitudes and behaviors that carry through into their later years (or are just as compelling when they don’t carry through).

But we see precious little actual boyhood in Boyhood. We see a lot of parenthood–but if I want to see a film about parenthood, I can pull out a treasured DVD and watch Mary Steenburgen blow Steve Martin until he crashes his car. By the way, Martin and Steenburgen’s older son in that movie? Anxiety-ridden Kevin? He’s a much more well-rounded character than Mason turns out to be in Boyhood, at least until the film’s final moments. So are all the kids in Apted’s Up series, who–even when they were seven, much less 14–showed that even little kids can have real, compelling ideas and attitudes and behaviors that carry through into their later years (or are just as compelling when they don’t carry through).

Of course, the lack of a real throughline for Mason’s character is in large part a function of the multi-year filming process, as well as the use of improvised setups and dialogue. Coltrane wasn’t ready to participate on that level when he was a little kid–and while I’m sure it was easy and fun for Hawke, Arquette, Linklater, et al, to sit around saying, ”Yeah, I did this when my kid was that age,” they don’t seem to have put enough thought into what their kids were doing or thinking at those young ages. In the end, the film consciously celebrates the idea that life is a collection of resonant moments, of the sort of ”snapshots” achieved via the film’s structure of dipping into Mason’s life for a couple of days at various stages in his development. (Mason turns out to be a photographer…get it?) I’d argue that such is not entirely the case, either in real life or (particularly) in the movies, and that the most valuable moments from a life are those that not only resonate, but evoke–moments built on emotions and behaviors that evoke where a person is now, and where he’s going in his life. I don’t feel like Boyhood accomplished that.

Clearly, plenty of others have allowed Boyhood to touch them in ways that it didn’t touch me. When I think back on the film, I remember that I never felt capable of losing myself completely in its fictional story, because every shift in Coltrane’s age/look/voice took me out of that story and reminded me of the real-world circumstances of the film’s creation. Perhaps that was just me being over-analytical in the moment–a personal flaw to which I cop wholeheartedly, and which drives my wife crazy (particularly when it resulted in you and me coming out of Schindler’s List (1993) on New Year’s Eve over-intellectualizing the little girl’s colorized coat, a moment for which Gwen will never forgive either of us). Or perhaps my failure to suspend disbelief was a function of my boredom with a film that rarely did more than scratch the surface of its protagonist’s developing persona. Either way, I suppose that someday I’ll have to go back to Boyhood someday to see if I feel differently on a second viewing. Considering the frequent fidgeting and sighing that caused Gwen to emerge from the theater saying, ”Well, I know you didn’t like it,” I imagine that if I do see it again, I’ll have to do so by myself.

BC: God, you were awful to go to the movies with. Were you this way during Austin Powers in Goldmember? Hardbodies? Better Gwen than me, anyway.

Just kiddin’. Come on over, we’ll watch the Blu-ray! Maybe we’ll get an extended cut.

After 3,000 words, with me positive if reserved and you, you, we’re at an impasse, and when you bring the likable yet totally different Parenthood (1989) into the mix, well, I don’t where to go. About Boyhood lacking boyhood; I didn’t feel that way, but perhaps I’m grateful for the absence of forced scenes with kids at play. (Maybe Linklater is rebuking the many films where kids seem entirely divorced from home life, or have stereotypically awful parents.)

And maybe, as we reach Boyhood length, it’s time to ponder some more in the Comments section, and invite other boys and girls to do likewise.

Comments