For almost 80 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose joins the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network to explore the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, we look back at a publication that’s been a force in American popular culture for even longer …

It’s a whole subgenre of celebrity photography — the snap of the movie star reading Variety. It never looks as candid as it’s meant to; the cover and headline are always plainly visible, and the intent look on the subject’s face tells us less about personal powers of concentration than about the significance of the publication in hand. Like so much in Hollywood, these shots blur the line between recreation and marketing, between human interest and business news. And really, in a company town, where the personal is the professional, what’s the difference?

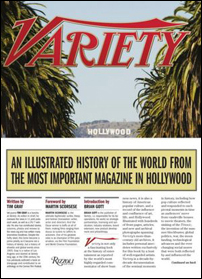

The shots may be fundamentally phoney, but the significance of Variety — celebrated in a huge and rather beautiful coffee-table book with text by Tim Gray, entitled Variety: An Illustrated History of the World from the Most Important Magazine in Hollywood — well, that’s indisputably authentic.

With the slow death of print and the atomization of entertainment journalism as it diffuses across the Web, it’s hard to credit how truly indispensable Variety was in its heyday. It was a one-stop shop, encompassing (to put it in Internet terms) the functions of Ain’t It Cool, Box Office Mojo, TMZ, Done Deal, Craigslist, Gawker, Rotten Tomatoes, and a fistful of others. For readers in the industry, it’s required reading. For those of us on the outside, it’s a fascinating glimpse into a privileged world, magical and disillusioning all at once as it lays bare the process of how the sausage is made. It is one of the few publications of which it can be said that the ads were often as informative — and as entertaining! — as the content.

It’s interesting to learn, from Tim Gray’s account, that Variety was founded at least in part as a bastion of critical freedom. In 1905, founder Sime Silverman legendarily gave up his gig at the New York Morning Telegraph to make an ethical stand. Believing that unbiased criticism benefited both the public and the artists — that is, the playwrights and performers whose work was under scrutiny — he borrowed from his father-in-law to start his own paper, conceived in principles of fairness and impartiality. Silverman publicly and consistently declared the ideals on which his new paper would be built, and decried the influence of money and sponsorship on content; he always disdained the then- (and still-) common practice of rewarding big advertisers with positive reviews. (The great composer Jean Sibelius once quipped that ”No statue has ever been erected to a critic,” but if you did, a statue to Sime Silverman would be a good place to start.)

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments