Released in March of 1992, Buffalo Tom’s third record, Let Me Come Over, was the beginning of a great string of records for the band. The follow-up, 1993’s Big Red Letter Day, sold even more copies and got them airplay well beyond college radio; subsequent albums Sleepy Eyed and Smitten strengthened their legacy, and more recent efforts like Three Easy Pieces and Skins showed that despite nearly a decade of dormancy, they haven’t lost their chops — or their songwriting gifts. It’s time to take a look at Let Me Come Over at the twenty-year mark — but before that, let’s retrace the steps leading up to LMCO.

Buffalo Tom released their self-titled debut in 1989 on the venerable California-based indie label SST. Labelmate and fellow UMass-Amherst classmate J. Mascis (Dinosaur Jr.) produced the record, which had lazy critics dubbing them ‘Dinosaur Jr. Jr.’ These were the same critics who, upon hearing a Rickenbacker, couldn’t resist using the term ‘Byrds-y.’ True, Mascis lent his trademark lead guitar to the track “Impossible” and guitarist Bill Janovitz displayed a penchant for distortion, but that’s really where the similarities end. Other standout cuts, like college radio staple “Sunflower Suit” and the blistering “Racine,” stood on their own as sludgy-yet-melodic rave-ups.

[youtube id=”t877jKDjpq0″ width=”600″ height=”350″]Either forewarned by Mascis or having had their own bad experiences, the band fled SST for Beggars Banquet/RCA for the sophomore effort, Birdbrain. Despite Mascis co-producing with Boston producer extraordinaire Sean Slade, the Dino Jr Jr tags all but disappeared. The title track got things off to a rousing start, anchored with a taut guitar riff that picked up where the debut left off. The album also literally referenced the debut in an acoustic reworking of “Reason Why.” The band also kept the acoustic guitars out for a nice version of the Psychedelic Furs’ “Heaven.” In between the leadoff title track and the slower acoustic material at the end, the band managed to work up a pretty good frenzy on cuts like “Enemy” and “Crawl.” The addition of Sean Slade behind the boards cleaned up the sound a bit without smoothing over the band’s ragged charm.

Whether it was a conscious move or just a byproduct of time, the band matured considerably on Let Me Come Over. The album still contained heavier riff-driven songs in the single “Velvet Roof” (with a  killer harmonica part) and songs like ”Larry,” ”Stymied,” and ”Saving Grace,” all of which could have been on either of the first two records. A major revelation however, were the band’s new emphasis on lyric-driven, melodic songs, only hinted at on Birdbrain. Janovitz wore his Keith Richards influence on his sleeve (he’d later write a book about Exile on Main Street for the 33 1/3 book series); “Taillights Fade” was the band’s strongest song to date, an aching semi-ballad with powerful lyrics and an indelible melody. The slow burn of “Mineral” is the album’s secret weapon, a sweeping, minor key song with an enigmatic “You’re so green” chorus. ”Frozen Lake” is another pretty acoustic ballad; the band’s softer side was really coming through, and it gave them another dimension. Twenty years on, Let Me Come Over still sounds fresh; no dated production, just a solid set of 13 tracks with nary a bum song in the lot.

killer harmonica part) and songs like ”Larry,” ”Stymied,” and ”Saving Grace,” all of which could have been on either of the first two records. A major revelation however, were the band’s new emphasis on lyric-driven, melodic songs, only hinted at on Birdbrain. Janovitz wore his Keith Richards influence on his sleeve (he’d later write a book about Exile on Main Street for the 33 1/3 book series); “Taillights Fade” was the band’s strongest song to date, an aching semi-ballad with powerful lyrics and an indelible melody. The slow burn of “Mineral” is the album’s secret weapon, a sweeping, minor key song with an enigmatic “You’re so green” chorus. ”Frozen Lake” is another pretty acoustic ballad; the band’s softer side was really coming through, and it gave them another dimension. Twenty years on, Let Me Come Over still sounds fresh; no dated production, just a solid set of 13 tracks with nary a bum song in the lot.

While Nirvana’s Nevermind usually gets all the credit for 1991’s sea change in the music world (U2’s Achtung Baby really oughta get some props, too), 1992 produced a bumper crop of career high water marks. Just a cursory look at the year’s releases reveals: Let Me Come Over, Automatic for the People, Copper Blue, Hollywood Town Hall, Check Your Head, It’s A Shame About Ray, Slanted & Enchanted, Dirty, Grave Dancers Union, Tender Prey and Bone Machine; among the best work for each band/artist.

While there was certainly a long drought of Buffalo Tom material from 1998 to 2007, the band never actually split, they just went on hiatus. I put some questions to singer/songwriter/guitarist Bill Janovitz and drummer/eponym Tom Maginnis about Let Me Come Over and what was going on with the band then (and now).

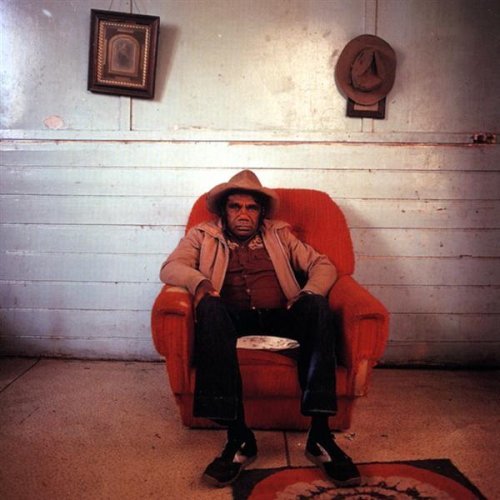

Who’s the person on the cover? He almost looks Aboriginal.

Bill: Yes, it was from a collection of National Geographic photos. This was from an Australian series by Michael O’Brien. I think Chris remembers the name of the subject. Mr. Brown? A rancher?

Let Me Come Over came out mere months after Nevermind, so presumably you were writing, recording and assembling the album in its aftermath. Was there any conscious acknowledgement of that, did you make strides to avoid it, or was it coincidence? Part of why I ask is that Frank Black/Black Francis said the Pixies covered ”Head On” because they kept hearing it every day in Los Angeles on KROQ, so I’d imagine you’d hear Nirvana songs on Boston radio.

Bill: No, you seem to underestimate how long it takes to make and release records, especially at that time. I’m pretty sure the record was in the can well before that. In fact, I recall being on tour for LMCO in Europe when Nevermind was coming out.

This might sound heretical, but while I liked them OK and totally respected them, Nirvana were never my thing as a fan. I rarely ever listened to them. I think I was most interested later in In Utero. I bet Cobain’s best work was before him. But as far as an influence either way, I can only speak for myself, not Chris or Tom, but Nirvana did not factor in any more or less than other bands around that time. In fact, we went on to Big Red Letter Day, which was more influenced by what the Lemonheads and other, rootsier combos were up to, I think. The Pixies were big influences for us as well as (obviously) Nirvana.

[youtube id=”GohsvUBhldY” width=”600″ height=”350″]Tom: I can actually speak to this in detail, as I happened to go see Nirvana play at Axis in Boston, the night before Nevermind came out. We were in Fort Apache [recording studio in Boston] finishing up some last minute tracks and overdubs for LMCO. I remember leaving the studio to go meet my girlfriend (future wife) at the club to see the show. She had actually tried to see them at MIT on their first record, but could not get in because she was not a student at the school (I believe we were on tour for Birdbrain then). So Bill is essentially correct, our third record was pretty much in the can before Nevermind came out. We had already recorded the tracks over three days at Bearsville (NY) and had a few things we needed to finish off before we started mixing.

There was a huge amount of energy at Axis — I remember when I got there and I see now from the club line-up card seen here that the Smashing Pumpkins played that night (must have missed them) and Bullet LaVolta played right before Nirvana, so our manager Tom Johnston, who also managed LaVolta can probably add more about this. I do recall knowing “Smells Like Teen Spirit” because I had heard in on WMBR (the MIT radio station) and it made an impression — big production, huge dynamics, very aggressive, but with pop hooks all at the same time.

Besides that, at the time I actually only knew a few songs from their first album when we were at the show. And we were so cool, that we even left before it was over! It was late, I’d been in the studio all day and probably had to work the next morning. To put a little bow on this whole thing, we played Reading Festival in 1992, which Nirvana headlined and I believe it was their last show on the Nevermind touring cycle. So those were the only two times I’d ever seen Nirvana, at a tiny club the day the record came out and the last show they played in support of that record in front of about 50,000 people singing every word….what a difference a year makes! Enough with the Zelig moments already!

[youtube id=”xbvrADHK9BM” width=”600″ height=”350″]How much camaraderie was there among you and your Boston peers? Did you ever consider signing to TAANG! before SST?

Bill: I think we would have loved to be on TAANG, but they probably passed on us. We played a lot with the Lemons, Blake Babies, Galaxie 500, and others, but we were on the road pretty early and got to know other bands from around the country and Europe. We did not feel like there was a “scene,” per se, but looking back, it seems there was something. A lot of it had to do with Fort Apache Studio, which was home base for a lot of these bands. We would see people at Christmas parties and passing in and out of the studio those first few years. But I remember meeting some Boston bands in far-flung places, meeting the Throwing Muses in Germany, e.g. in 1989. Though we went to UMass at the same time as Charles and Joey in the Pixies, and we saw them play later at very small clubs, it was only while recording BRLD in LA in 1992 that I recall meeting the band.

Tom: Not a lot to add to this, as Bill is right on. We got to know bands by playing shows together and that tended to happen more outside of Boston as time went on and we were all on the road in vans. Lemonheads, Blake Babies, Dino Jr., and Sebadoh were bands we got to know the most because we played a lot of shows — one-offs in Boston and/or a string of dates on the road.

Was radio a big factor for you coming up? Locally and nationally? With alternative radio dying nationwide in the last decade, it’s tougher for certain bands to get on the air, but Buffalo Tom seemed to get a fair shake. Was MTV at all a factor?

Bill: We had a good look at MTV; they were pretty fair and generous with us in getting exposure, even in the early days, on shows like 120 Minutes. Before and concurrent with that was the ultimately important college radio play, which from start to finish was the major exposure we got in the States.

Much of it, however, was buzz that filtered back to the US from the UK, where we received early favorable reviews and coverage in the weekly music papers, like Sounds, Melody Maker, and NME, as well as play on BBC radio, such as an early Peel Session. But we did not get consistent mainstream US radio until Sodajerk. And even that only lasted a record or two. Our appearances on the Jon Stewart and Conan O’Brien shows as well as My So Called Life were hugely significant in boosting our profile, if not record sales.

[youtube id=”RyUnP3y-QRk” width=”600″ height=”350″]Not to slight the other albums (which I like a great deal) but I believe LMCO was your creative high-water mark. Would you agree? If not, what’s your personal fave?

Bill: I think it was our breakthrough creatively, in establishing our style, sound, and songwriting. However, I honestly think our peak sustained through BRLD and Sleepy Eyed. I think those three records are very solid and I am very proud of that run. But I see all of our work, including our last few records, as a relevant continuum, and artistically solid, with some individual peaks equal to those early records. It is just that the context of the times is different. Listeners also bring their own experience. For those in their 20s and 30s, those records meant a lot to them, more than our current records could for them in their 40s.

Tom: Personally, listening to LMCO frustrates me, because I don’t think the production (time/money spent, studio knowledge) are equal to the quality of the songwriting. The songs deserved better, but it was a factor of the times — low budgets, little studio time, etc. My drumming in particular is pretty erratic. Lots of youthful energy, but a bit all over the place… and most of the time way too fast! I agree with Bill’s take about these albums. Here is my quick review of those three records:

LMCO: best songs

BRLD: best studio production

Sleepy Eyed: best studio performances as a band

Any plans to revisit LMCO for the 20th anniversary of its release? I love what Big Dipper did with that Merge boxed set. Are there any outtakes or bonus material worth unearthing from the era?

Bill: No plans. We had our 25th band anniversary in Boston this past fall. Enough nostalgia for the time being.

Michael Azzerad’s (excellent) book Our Band Could Be Your Life basically posits the notion that indie labels weren’t that much better at managing their finances than the majors and that SST was notorious for underpaying bands. Was that a factor in your jump from STT to Beggars/RCA after the debut?

Bill: Yes, precisely, as well as wider distribution and exposure. Very accurate and interesting book. That captures the years — and indeed, months — leading up to our first record on SST.

Tom: I agree, but in defense of SST, they also signed bands to one-album contracts, which was not standard practice. Most small labels at the time would try to tie up bands to long contracts then sell them off to big labels once they got some success. We were free to walk after the first record, no strings attached.

[youtube id=”OJ09IPoF3os” width=”600″ height=”350″]Bill, I love your Part Time Man of Rock blog/concept. Any plans to compile your Web tracks into a collection, or will you keep releasing them free on the site?

Bill: I toyed with this idea, and may still do so. But I have this other project I am working on now (see below). Maybe I will compile the covers and essays at some point in the next year or two. Thanks for the kind words.

Bill, I know you’re a realtor now and still make music for your blog and wrote a great book on Exile on Main Street. What’s next for you? And what are Chris and Tom up to these days when not playing Buffalo Tom gigs?

Bill: I am currently working on a solo “album,” seemingly for online only. The first song is up at billjanovitz.com, along with an explanation of the project. I am always writing as well. I may have another book soon. We will see.

Tom: I work at a publishing company north of Boston and play with a soul/funk cover band once in a while just for kicks.

Comments