The art of film involves many collaborators, the most important of whom — as I’ve written before — is the audience. We are more than passive receivers. It is we, the audience, who bring the movies to life. Writers and directors create scenarios, and actors play them out, in immersive environments created by composers, designers, and cinematographers. But it is inside the viewers’ heads that a film truly lives. In our heads, and in our hearts.

The art of film involves many collaborators, the most important of whom — as I’ve written before — is the audience. We are more than passive receivers. It is we, the audience, who bring the movies to life. Writers and directors create scenarios, and actors play them out, in immersive environments created by composers, designers, and cinematographers. But it is inside the viewers’ heads that a film truly lives. In our heads, and in our hearts.

Great filmmakers know this, and enlist the audience’s collaboration by crafting films that engage our intellect and emotions. Not-so-great filmmakers grasp the same principle, but engage with it in a different, far more crass way — by monetizing it.

Film is unique among the arts in that its mode of presentation has been in constant flux from its inception. While styles of contemporary painting, say, have changed tremendously since the 1890s, the experience of looking at a painting in a museum or gallery is still recognizably the same; but a host of technological advances have fundamentally altered the way we go to the movies. Some, like synchronized sound, color, and widescreen, have proved permanent additions to the cinematic experience. Others — Smell-O-Vision, SenSurround, even 3-D — have remained little more than novelties.

But they keep coming back, and the state of the art keeps moving on. Innovations come and innovations go. And all of them, game-changers and gimmicks alike, are driven by the same impulse; to find a deeper connection with an audience. All of them are predicated on the underlying assumption that the film-going experience — however it exists now, however it has moved on — remains somehow inherently incomplete.

Again, this is unique to the medium of the movies. To return to painting for a moment, nobody ever looked at a Cézanne still life and thought it could be improved by fixing it so you could smell the fruit, or that feeling the rumble of the surf would enhance your appreciation of Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa.

But cinema is an immersive artform — so much that we cannot help but wish it were moreso. It comes just close enough to replicating the experience of living to tease us with the possibility. And so the state of the art moves on, and cannot be satisfied with anything less than full-on virtual reality.

Or not. Film has been pretty good at finding new ways of involving our senses; but the hallmark of true life experience — and the endgame for “interactivity” — is to engage the higher functions of our brains; reasoning, decision-making, problem-solving. And that has proved elusive. For the most part, the greatest workout our decision-making faculties get at the movie theater (after choosing which movie to see, of course) is determining whether to get that awful fake butter on our popcorn. We may spend some time after the movie making determinations over the meaning of what we’ve just seen, but that’s a far remove from the experience of living, where our decisions effect what we see even as we see it.

It’s a high hurdle to clear, even with technological assistance. That hasn’t stopped some filmmakers from trying, though. In 2010, a German thriller titled Last Call used a combination of cell phone technology, voice recognition, and branching menus to bridge the gap between audience and actors. Audience members provide their phone numbers before the movie rolls. (At these screenings, you’re allowed to keep your phone turned on!) During a crucial scene, the character onscreen makes a call — and connects with a random member of the audience. That person’s voice instructions then influence the outcome of the movie’s action.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qe9CiKnrS1w

Last Call — which the producers bill as “the first interactive horror movie,” although the word they’re really looking for is “participatory” — was an interesting experiment, a first step. But with branching decision-tree technology so cheap and ubiquitous, it’s easy to envision where the model could go from there. Imagine the armrest of your theater seat wired with two buttons — like one the US congress uses to register “yea” or “nay” — and a film potted out with flowcharts instead of storyboards. At every turning point, two options would flash on the screen, and a simple-majority instant poll of the audience determines the next twist. It’s entirely doable.

The thing is, there’s already a medium that pretty much works this way: game design. Integrating a choose-your-own-adventure element into filmmaking — making movies more like games — seems like a losing proposition. It’s a bit like dancing about architecture, trying to convey the strengths of one medium in another that is not particularly suited to those strengths. There are already emotionally gripping, ethically complex videogames, like The Walking Dead or The Last of Us, that depend entirely upon behavioral choices — and they don’t cost you twelve bucks (plus price of popcorn) every time you want to play them.

So there will likely be no full-on charge towards integrating game mechanic into the movies. But with the proliferation of cross-marketed franchises, we can expect to see more movies based on games — and with them continued gestures toward a ludic approach to movie-watching. I recently had occasion to watch Professor Layton and the Eternal Diva, an anime spun off from the popular puzzle-game series for the Nintendo DS. The Layton games have sold upwards of 15 million units altogether; developed in association with psychologist Akira Tago — a pioneer in the field of “brain training” — they are deliciously addictive. While the scenarios are inconsequential, pseudo-Victorian hokum, their main attraction is the array of brain teasers on offer. Their integration into the narrative is rarely more than cursory; the titular Professor Layton — an archeologist with a sideline in crimebusting — needs information to crack a case, and the interviewee refuses to come across until he’s found the area of such-and-such a triangle, or traced a certain route so that it never crosses itself, or successfully identified different views of an irregular solid rotated in 3D space. The player must solve literally hundreds of such puzzles to complete each game.

The Eternal Diva movie teases us with its setup — a group of stranded theater patrons follow numbered clues in hopes of finding the secret of everlasting life — and even frames the clue sequences in such a way as to recall the videogame. The clue-number appears onscreen, and the characters (and, presumably, the audience members) fall to silent contemplation, all to the accompaniment of a musical motif as familiar to Layton fans as the classic “think music” from TV’s Jeopardy!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUc9Oz4cN9U?t=21m54s

This is mildly amusing, at first, even though we know that the movie — unlike the games — will keep rolling on even if we fail to come up with the right answer. But — as much as your Old Professor is loath to denigrate the work of a colleague — Professor Layton and the Eternal Diva ultimately feels like a cheat. There are only a handful of puzzles in the movie, and they’re all based in elementary wordplay rather than the math and spatial geometry of the games. This shifts the focus inescapably to the weakest aspect of the franchise — the steampunk flapdoodle of the plotting.

Another film that feints rather more successfully towards the mechanics of the game that inspired it is Clue. This 1985 farce, based on the classic boardgame, is not only a fiercely witty sendup of the whodunit genre — it was originally rolled out to theaters with three different endings, each plausible and consistent with the previous events of the film. Which ending you got depended on where and when you saw the movie.

Clue’s alternate endings, though, only became a selling point when the movie hit home video. It was a bomb during its theatrical run, and crapshoot quality of the endings is often cited as a reason: “[Producer John Landis] thought that what would happen was that people, having enjoyed the film so much, would then go back and pay again and see the other endings,” says writer/director Jonathan Lynn. “In reality, what happened is that the audience decided they didn’t know which ending to go to, so they didn’t go at all.”

But there is at least one film that very successfully plays the multiple-ending game — the film that gives this week’s column its header image. That happy-looking jasper up above is Mr. Sardonicus, title character of William Castle’s 1961 B-movie Gothic.

Castle was a true original. He styled himself as a sort of downmarket Alfred Hitchcock — an auteur who was also a showman, who spun his public persona into a brand. Movie posters and tie-in merchandising were emblazoned with a silhouette of Castle in his director’s chair, cigar jauntily aloft — an image reminiscent of Hitchcock’s signature profile. In place of Hitch’s cool European irony, though, Castle projected a gleeful huckster vulgarity that is thoroughly American; Hitchcock may have been his role model, but his spiritual godfather was P.T. Barnum.

Known as the King of the Gimmicks, William Castle came off like a cross between Roger Corman and baseball impresario Bill Veeck. This academic paper ties him conceptually to a cinema tradition stretching back to George Méliés, in his energetic tweaking of the fourth wall — but there was nothing highbrow about his technique; his self-proclaimed goal was simply to “scare the pants off America.” Castle’s operating principle was that a trip to the movies should be an event — and with a string of low-budget shockers through the 1950s and ’60s, he set out to deliver just that.

These days, the “wide release” is standard practice, with any given movie opening in hundreds of theaters simultaneously, and a movie’s fortunes depend almost entirely on a single weekend’s grosses. In the days before the consolidation of theater chains, though, it was common for smaller movies to roll out piecemeal, over a period of months; distributors would truck a handful of battered prints from town to town.

These days, the “wide release” is standard practice, with any given movie opening in hundreds of theaters simultaneously, and a movie’s fortunes depend almost entirely on a single weekend’s grosses. In the days before the consolidation of theater chains, though, it was common for smaller movies to roll out piecemeal, over a period of months; distributors would truck a handful of battered prints from town to town.

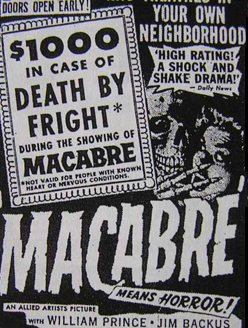

This roadshow approach allowed for all manner of stunts and promotions, and Castle used ’em all — from simple gambits like planting ringers in the audience to scream or faint on cue, or hiring teenagers to don rubber masks and run around the theater during the scary scenes, to conceptual gags like “Fright Insurance” (which promised your next-of-kin a hefty payout if you died of fright during a screening of Macabre), to low-tech gimmicks like flying a plastic skeleton out over the audience on a zip-line (House on Haunted Hill’s “Emergo”) or wiring select theater seats with joy buzzers (that was The Tingler’s “Percepto”). These flimflams made the movies interactive before “interactive” was a buzzword. But none of Castle’s productions were quite so participatory as Mr. Sardonicus, which offered viewers the chance to influence the outcome of the film.

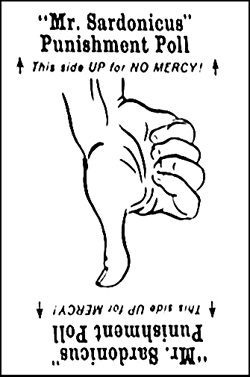

The gimmick for Mr. Sardonicus’ theatrical run was the ”punishment poll.” Before entering the auditorium, each member of the audience was handed a placard, printed with a glow-in-the-dark hand with extended thumb. The placard’s purpose being not immediately clear, they would settle in to watch the action unfolding on the screen.

What they would see is a handsome little movie. Watching it today — you can see the whole thing on YouTube — Mr. Sardonicus has the same vaguely-Mitteleuropean gloom that characterizes Roger Corman’s Poe pictures. The title character, played by Guy Rolfe, is a shady aristocrat, lurking about his castle, hiding his face from the superstitious locals. In flashbacks, we learn that he was once Marek Toleslawski, a common peasant with a lust for wealth. Marek’s father, dreaming of a better life for his son, buys a ticket for the national lottery, but dies before the drawing and is buried with the ticket in his pocket. The ticket, of course, proves to be a winner. So consumed is Marek by greed that he violates his own father’s grave to retrieve the ticket and claim the enormous jackpot. He succeeds — but is so traumatized by the sight of his father’s grinning skull that his own face is permanently fixed into a hideous contorted leer.

In a melodramatic irony worthy of a Vault of Horror comic book, Marek gets what he thought he wanted while losing everything that really matters. His riches buy him a castle and the bogus title of Baron Sardonicus, but his wife is driven to suicide by the sight of him. Don’t feel too bad for him, though; seeking to cure his horrible rictus, Sardonicus resorts to weird science, murder, and extortion — even threatening and betraying his second wife.

In the end, an experimental treatment wipes the smile off Sardonicus’ face — but leaves him with his face completely paralyzed, unable to speak or even eat; he seems doomed to a slow death by starvation. The film holds out a momentary glimmer of hope when it is revealed that Sardonicus’ condition is entirely psychosomatic. If told this, he will almost certainly be fully cured, repent his evil ways, and reform his life.

At this point, the narrative pauses, and director William Castle appears onscreen to address the audience directly.

Now, the execution of the “punishment poll” was different from theater to theater, and the specifics are faded with time, hazy memories, and a fog of self-aggrandizing bullshit. But there’s an odd little cut that makes me assume that — in selected theaters, anyway — the projector was briefly shut off, allowing the ushers to tally the vote and the projectionist to change reels, as necessary. If the poll went one way, the benign ending would be screened; if it went the other, Sardonicus was doomed, and the projectionist would roll the bleak ending.

Ostensibly, at least.

Because here’s the thing: While Castle maintained for the rest of his life that he had indeed shot a “merciful” ending to the movie — stating as much in his autobiography Step Right Up! —the fact is that no one can seem to remember ever seeing it. If any such ending existed, the print has been lost. The overwhelming likelihood is that such an ending never existed in the first place— that the whole thing was an elaborate ruse.

Interestingly, even while claiming he did shoot an alternate ending, Castle states in his memoir that he did so at the insistence of studio bosses, who were covering their asses in anticipation of an audience rebellion, should the supplied ending not match their wishes. William Castle, of course, knew better. You can’t be an effective huckster without a keen understanding of human nature, and Castle had that in spades. He understood that an audience is a mob, and what mobs want is mob justice; and moreover, that the illusion of choice is just as satisfying as the real thing.

Comments