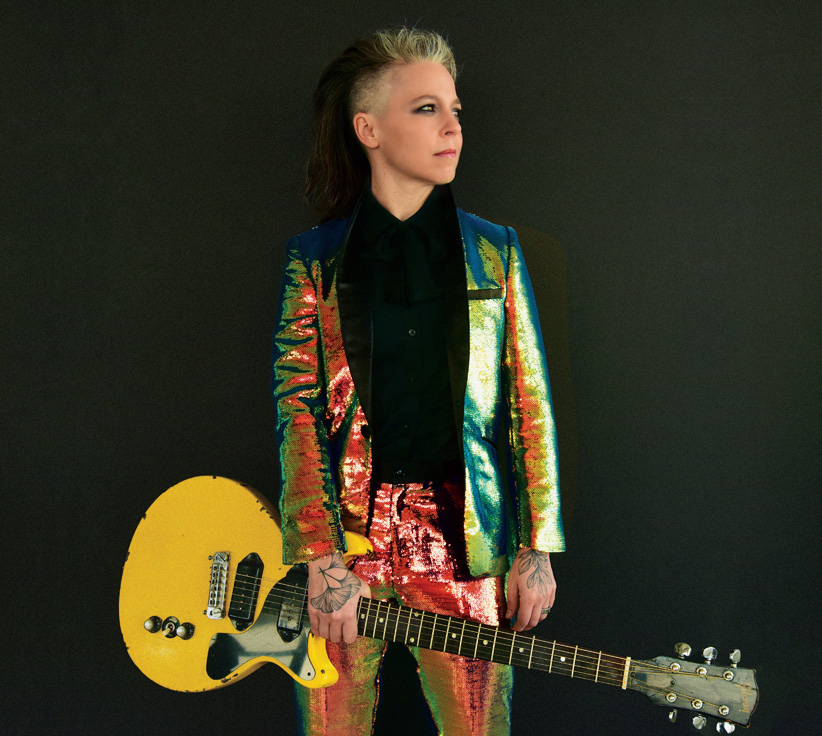

With superb musicianship, terrific wit and an unerring bullshit detector, Erin McKeown has spent the last 20 or so years quietly amassing a consistent, endlessly rewarding body of work. Easily metabolizing a range of influences, she freely picks and chooses from Tin Pan Alley pop, jazz standards, folk, and classic and indie rock, with a drop of slam poetry for good measure, effortlessly hopping between genres without a whiff of pretentiousness or showing off. Her 11th album, Kiss Off Kiss, continues her winning streak with a batch of pointed, personal songs, this time brought to life with help of producer Steve Berlin, who brings a subtly textured soundscape to McKeown’s customarily literate, emotionally charged poetics.

In a recent update to her email list, McKeown spoke candidly about the struggles of a touring musician in a not-quite-post-pandemic world, and when I spoke to her, we explored that topic in greater depth. We also discussed the genesis of Kiss Off Kiss, as well as how a former Christmas-hater came to appreciate the holiday hang.

I feel like, just given the tenor of the times, the first thing you ever want to ask someone when you meet them is: “How are you doing? How have you been?” So, how are you, Erin?

A mixed bag. I think that’s the late — hopefully late-stage pandemic. I had a great 2020. I was just telling a friend this morning. I had a great 2020. The first part of the pandemic suited me quite well. The quiet life and the lockdowns, I wasn’t trying to be out on the road and I live in the middle of nowhere anyway, and so it was great. I have found this aspect, this time of the pandemic, harder in terms of wanting to get out and do things and put this record out, and all that’s running into the — as I was saying in my newsletter — kind of running into those walls in addition to the usual walls that happen in the world. So, a mixed bag.

You know, I have some friends staying with me that played a show with me last night. I had great shows this weekend with my band. I haven’t had a band play a show with me in years! That’s great. So that’s what I mean by mixed bag.

Did this whole experience — lockdown, not being able to play out, and all this stuff — did it change how you think about making music, why you make music?

Sure! Oh, yeah. Well, I’m someone who doesn’t … first of all, I don’t really listen to music. [laughs] It’s actually not an unusual answer from professional musicians.

I kinda hear that, yeah.

Yeah. I mostly watch, like, prestige cable TV and listen to audiobooks and podcasts. That’s pretty much what my media diet is, so I don’t really listen to music and I definitely don’t play music if I don’t have to. And that’s been that way for a number of years. And then what happened in the pandemic was that I found myself interested mostly around writing, like writing songs just for the sake of writing them. I’ve been in this weekly writing group for years, and I really doubled down on that, with no intention of making an album or anything. And I really felt like I re-discovered that experience that I had as a teenager of just being like, “this is really fun to just make songs,” without having to think about all the other stuff that goes with what happens if you want to put those out in the world. So, in that sense, just the joy of creation. I mean, I also made a lot of videos in the pandemic and I did a lot of writing, just of all kinds. So I was just, like, super creative, but especially around music. That remembrance of that initial spark and excitement of it really happened for me.

I know — because I read it — the story of how you ended up making this record. Just briefly, like, so you literally got a check in the mail?

Yeah. Yup. I had a friend, a great friend of mine whose family had essentially made a widget, a long time ago, for I think some part for an airplane or something, I’m not sure. But anyway, so they were born into a family that had wealth and interest in this property, this widget or whatever it was. And it recently got sold, so they came into a bunch of wealth. And they decided to give it away, and they gave it away in a very thoughtful, very anonymous, unexpected way. I did not know this check was coming, it literally just came in the mail, and it came with kind of a form letter. I mean it definitely said like, handwritten, “Dear Erin” at the top, but the rest of it was a form letter of like, “This is the land that was exploited for this widget; these are the people whose labor was exploited for this widget; this is the benefit that my family accrued; this is what I’m doing with it.”

And I’d never received anything like that before, but the way it was done allowed me to receive it with such joy, you know? I didn’t feel like I’d been picked out because my shoes were worn through, or something, or like somehow I was needy, or it was charity, or any of those things that can get in the way of you receiving a gift. And honestly, my first thought was my dumbest thought, which was, “I’ll make a record with this.” And I wouldn’t have made the record without that chunk of money.

Were the songs written already?

No, nope, the check came in March 2020, maybe the 8th or 9th—like, days before the world shut down. And then I wrote the songs sort of over here [gestures] for fun over the summer, and there was some mysterious moment that my therapist and I are still trying to untangle [laughs], where I decided to take these songs that I had written for fun, that I didn’t intend for anyone to hear, and make a record of them. When I had apparently told my therapist many times, “I’m not doing this anymore.” So we’re still trying to figure out that moment. But yeah, it was really pretty quick at the end of the summer, I was like, OK, this chunk of money is going to go with this piece of songs, and I called Steve Berlin of Los Lobos probably in September, and within two or three weeks, we had a studio date and a band booked, and we were starting at Thanksgiving.

How did you know Steve?

I met him through an artist activist boot camp retreat that I had done for several years in New Orleans a long time ago. A nonprofit used to do these retreats where they would bring 15 or so artists to New Orleans once a year, all expense paid, and you’d basically sit in a room and talk about what works, what doesn’t work in terms of being an activist, how you can get better at it, networking, and then of course doing things in the community of New Orleans while you were there. So Steve had been in one of my cohorts of that, probably 2009, 2010, and I’ve been a Los Lobos fan for so long, I just, I love that music. He’s just a rad guy, and he’d made some records for some friends of mine, and he’s always been on a list in my brain of, like, “Next time I have the means to make a record and have a producer, he’s on my list.”

What’s it like being in the studio with him? What kind of producer is he?

[laughs] He’s—I’m so glad you asked, because not many people have been asking about it—he’s … I don’t know anyone who likes making records more than him. Just his excitement about the actual process was so notable. He was just, like, in hog heaven. Every single song, he was like, “Aw, why don’t we try this amp, and this set of pedals? And, aw, let’s change the cymbal, and do this and this, and what if the bass used this sound?” He was really into tone and vibe and sound. I had made very, very detailed demos of these songs, where I played all the instruments, and basically the band that came in played my demos essentially note for note, but in Steve Berlin’s, like, soundscape world. That was really cool.I mean, my abiding image of him from making the record is like—I think I have a picture of it, but we made it in a studio in Portland, Oregon that is the studio of the frontman from Modest Mouse [Isaac Brock]. And he’s just like, I mean … four gold records’ worth of guitar shit around. [laughs] And he’s got a freight elevator where every surface has got guitar pedals like, stacked. It’s called the Pedalvator. And so there’s an image I have in my head of Steve, he went and grabbed, really, like eight pedals from the Pedalvator and he put them all in a line in the floor and decided which order they were gonna be in. He’s sitting cross-legged on the floor, twiddling knobs, so excited to find this sound with all these things from the Pedalvator. That’s what it was like making a record with him. He was a great leader, real easygoing, and assembled amazing people. I let him do everything: he picked all the people, he picked the studio, he picked the engineer. Lo and behold, it was an engineer that I had done two projects earlier with [Brandon Eggleston], that he didn’t know that. But it was a nice sign that he understood my vibe, and like the kind of music and ways that I like to work.

What do you generally want in a producer?

I want someone who answers questions definitively. Like, you know that joke, “How many producers does it take to screw in a lightbulb?” “I don’t know, what do you think?” I am just not into that. I told him from the beginning, I was like, “I need a captain. You are in charge. I want answers.” I don’t want to be, like … pull and push at an idea forever, I just want someone to make a decision and we keep moving, and to be in charge. I do so much in my creative life where I’m the auteur and very much in charge, and I really wanted it to be … I really wanted to walk into Steve Berlin’s world. And of course, every once in a while, I was like [grunts complaingingly in a Snidely Whiplash sort of way I really wish I could reproduce in words], but he did exactly what I asked him to do. He was a great leader and very decisive, and those are totally the things that I want out of a producer.

OK, I want to go back around to what you talked about in your last e-blast, and I actually want to quote a bit of what you wrote. You wrote, “this particular tour feels like a real now or never, maybe the last time i do this”™ kind of high wire act.” And you talk about how your shows are struggling to sell, lots of people you know, their shows are struggling to sell, and I just want to get your take, like, what’s happening? Is this just a temporary pando thing and it will pass, or is something actually different now that we’ve been through all this?

I love thinking about this. I don’t love the topic, but I love thinking about this. I think you phrased it really beautifully. In the short term, I think people don’t feel safe. Honestly, I don’t know the science to know whether they are or they aren’t safe if they go to shows. So, I can’t say, but I know that people don’t feel safe. I certainly know that people are like, “Are you crazy? Why would I do that right now?” Some of that is because their kids aren’t vaccinated, some of that is because they have health issues and some of it is just, it seems really unclear and, like, we’re not sure.

And the other piece of your question—has something changed more permanently—feels really interesting to me. I guess anecdotally I’ve had a lot of conversations with people, and I guess I can only speak for … these are middle-class white people in our 40s [laughs], mostly that’s who I’m talking to, who are all essentially saying, “I realized I don’t need to go out as much as I was going out. I was feeling more pressure to be more social than I wanted to be. I was busier than I wanted to be.” And the pandemic was something of a reprieve or a reset or an opportunity to rethink that, and I think maybe on a larger scale, people are thinking more about their leisure time and what they want to do with it. And it may not include as much … going out in public. I would wonder if restaurants will see something similar to that. I mean, what I do has always been extraneous, in the sense of like, it’s a leisure activity. It’s totally like, after you pay your rent and feed your children and pay your cable bill, if you have money, you might go to a concert, do you know what I mean?

Yeah, yeah.

I’m not essential in that way. I remember 2008, 2009, when the big financial crisis happened. Similarly, shows just really cratered. People did not have that extra money. I think people are reconsidering what they want to do with their time, as well. And of course, there’s always this other piece of it for me, which is, I just told you, I don’t listen to music! [laughs] And I don’t go to concerts. And I’m pretty typical for my demographic and age group. Things change in life. Think of how much music you bought in your 20s, and how many shows you went to see in your 20s and it’s just, you don’t do that anymore.

And I have to tell you, I don’t think it’s a bad thing if the pando has changed our social habits, you know? If it means people are slowing down, or relaxing more, or spending more one-on-one time with their families, or being outside more? I don’t think those are bad things. Even if they make me sad [laughs] and affect my career.

Is playing live for you something you need to do to make a living, or is that something you would do for free if no one paid you?

I do it to make a living. I mean, I certainly like playing live, and it’s a certain kind of adrenaline and communion with a room full of people, but I would be very happy doing that, like, twice a year. That’s just me, it’s always been like that for me. The problem with doing it twice a year is you’re not going to be very good at it [laughs], because it’s a muscle that has to stay trained. It’s not easy to get up and play in front of people if you haven’t done it in a while, so you kind of have to, in order to be satisfyingly good at it for yourself, you have to keep doing it. But as far as my need to do it, I’d be happy to do it twice a year. I am essentially a shy, pretty introverted person. I was terrified, full of stage fright for almost my entire life until high school, and then when I started playing music out, I would throw up for days ahead of a gig. It was really, really hard for me, and as much as I seem at ease, and you know, like a trouper and an old vaudevillian or whatever who’s comfortable with all of it, it’s a very hard-won comfort, because it was really, really hard for me when I first started.

We’re almost out of time. I did want to ask you one thing because, they’re going to be starting to hang Christmas decorations in stores soon—

[McKeown laughs]—that time of year is coming, and as you are the creator of Fuck That: Erin McKeown’s Anti-Christmas Album, I wanted to know: does a pandemic make Christmas more tolerable or less?

I just realized as you were talking, this is the ten-year anniversary of that record!

Oh, god.

I know, it’s crazy. You know, I feel … I’m so much less angry about Christmas than I used to be. [laughs] It’s really past for me, and I think making that record was actually very helpful, and the years that I toured it was very helpful in relieving my inarticulate childhood anger about that. [more laughter] So I’m much more chill about it these days. I love kitschy Christmas stuff, because it’s just so stupid to me. I can’t believe this whole industry that’s around it, and I certainly like to troll people who are super into Christmas. So I get enjoyment out of that time of year for those reasons, and my upset and annoyance and anger at Christmas is so much less than it was in 2011 when I made that record.

What’s the least objectionable Christmas song for you?

Oh, gosh. It’s funny because I have these rock and roll aunties and I do my holidays with them, and they’re musicians as well, and they always invite musicians, so there’s always a Christmas singalong. [laughs] And they allow me to play, like, a few of my anti-holiday songs at the Christmas singalong, and they know them by now, and so it’s fun. But they are singing traditional Christmas songs and, um … gosh, what is … [McKeown pauses]. There’s something about a sledding—like, a sledding song. [laughs] I can’t think of it right now!

“Just hear those sleigh bells jingling,” that one?

Well, I like that one, yeah, and there’s another one about … I can’t even think of it right now, but I have an image of [makes surfing gesture] like a sled bouncing over snow, and horses, or something. And I like singing that one, when we literally sit around with a piano and a guitar and a pile of sheet music books and sing the songs. As anti-holiday as I am, I appreciate … the hang.

[Laughs] I was going to say it’s so Victorian, but it’s a Victorian hang.

[laughs] Yeah, it’s a Victorian hang, and it’s like, two women that have been together for 35 years, and me and my queer family, and then like these other, you know, so it’s … that’s the queer Christmas. We have queer Christmas, as much as we can.I would think “Itsa Very Queer Christmas” would go well in a setting like that.

Oh yeah, I wrote that song! I forgot I wrote that song.

I love that one.

[laughs] That’s probably one of the … the truest, most personal songs on that record. It’s so nice to just not be that mad about it anymore.Kiss Off Kiss is available via BandCamp through a pay-what-you-can model; you can also trade an object to receive a digital copy.

Comments