When it comes to phrases intended to serve as a call to drop everything and get the party started, few hold quite the same kitschy appeal as these four words: “Everybody Wang Chung tonight.” Thankfully, Jack Hues, the man who first sang that lyric, has always had a sense of humor about the place where he and his longtime musical associate Nick Feldman have found themselves in the pop culture pantheon, possibly because they are comfortable in the knowledge that, for millions of fans, the legacy of Wang Chung consists of far more than their signature tune, “Everybody Have Fun Tonight.”

Hues and Feldman have taken a few hiatuses from Wang Chung over the years, but at present, not only are they back together and touring the world and elsewhere, but, indeed, they’re actually daring to work up a bit of new material. Yes, we know: the idea of a band who could easily coast through the remainder of their existence by playing their hits on the ’80s revival circuit taking the time to write, record, and release new music sounds crazy…but, dammit, it’s so crazy that we’d like to think that it just might work. Details of their new material and a free download of one of the new songs can be found on their website (along with a very funny video which reemphasizes the aforementioned sense of humor), but if you’re looking for information on the band’s history, you’re in luck: Jack Hues was willing to sit down with Popdose and let us pick his brain on the life and times of Wang Chung.

Popdose: I figured we’d start by talking about the evolution of the band, but since you and Nick have worked together since the late 70s, I guess it’s best to preface that by finding out how you and he first met.

Jack Hues: Well, there’s a reasonably well-documented story… (Laughs) …of me answering an ad in the Melody Maker, which was a British music paper at the time, with ads in the back for musicians. There was this ad that was bigger than all of the others, which sort of fooled me into thinking that he had some sort of deal or whatever…which, of course, he didn’t. But we hooked up, and I was doing a bunch of auditions at the time, having just finished at the Royal College of Music and decided that I wanted to get back into pop music, having studied classical stuff for awhile. Yeah, Nick at that time was played with a drummer called Paul Hammond…who’s passed on now, God rest his soul, but he was the drummer in Atomic Rooster, and a really fantastic drummer, actually. I remember jamming with them: Paul and Nick and myself and a bass player whose name I don’t recall. We just had a lovely afternoon, basically, and Nick and I hit it off. And that’s where it all began, really.

I know you guys were first in a band called the Intellektuals, which was followed by one called 57 Men. As a fan of music family trees, I was fascinated to learn that 57 Men ties in not only to Wang Chung but also Heaven 17 and Bow Wow Wow.

That’s right! It was sort of a meeting place for fairly talented people. (Laughs)

Given the disparate sounds of those bands, can I presume that musical differences had something to do with the dissolution of 57 Men?

I guess so, yeah. I mean, I think that back in those days there was quite a…how do I say this?…a structured way that you approach the business, which was that you wrote some songs and you rehearsed them with a band. I think Nick and I, by this time, had decided that we should get a proper singer, so we got Glenn (Gregory). And Leigh Gorman, the bass player, used to work a lot with Darren Costin, who was the drummer in Wang Chung. They were a little rhythm section together. And, potentially, the pattern would be that we’d rehearse, then we got some gigs on this little pub circuit in London, which is where A&R guys would hang out. They’d check you out, and you’d do this pub circuit for three or four months, and if you hadn’t gotten signed by then, it was back to the drawing board, and that usually meant that everyone went their separate ways. But Nick and I stuck together…and Darren, at that point…and decided that we should slim it down, because 57 Men almost was 57 men. (Laughs) There was something like seven or eight of us — it was far from an economic prospect — so we stripped it down to a 3-piece, and the three of us did the first demos and started up the Huang Chung project.

What gave you the idea to take on pseudonyms in the band?

I think everybody was doing it, actually. Johnny Rotten and…uh, I can’t think of anybody else! (Laughs) I thought Joe Strummer was a pseudonym, but, of course, it’s not . Everybody else dropped their pseudonyms after awhile, but mine has stuck. I sometimes wish I’d gone back to my real name, but I think perhaps me more than the others needed to have a pseudonym…an alter ego, a double identity so that I could deal with all of the rigors of being in the business. (Laughs)

There are some purists out there who feel that you guys have never managed to top that very first album, when you were still calling yourselves Huang Chung. How does it hold up for you?

I like it…and I can sort of sympathize with their viewpoint. (Laughs) It’s sort of undiluted, that record, and I think I was writing…well, you know, having spent three or four years studying classical music, people say, ”Oh, Jack, you’ve got classical training.” I didn’t really get into classical musical until I was 17 or 18. But listening to Stravinsky and Prokofiev, you start to get into the way the harmony works and…it’s hard to explain it in layman’s terms, but there’s a sort of sparseness in the harmony, and I think I translated that into guitar chords and stuff. That kind of fitted in with the punk aesthetic, in a way, where everything was more angular, and that first Huang Chung album benefited from that fusion of my sense of Stravinsky and the Sex Pistols. (Laughs)

Is there anything from that record that you still revisit for your set lists?

No, although “I Never Want To Love You In A Half-Hearted Way,” Nick and I were talking about how, if were going to do any of the tracks on that album, I think we might do that. I think that’s something we might get practiced up while we’re out on the road and maybe drop that in a few of the sets.

The slight change in the name, from Huang Chung to Wang Chung, was that a contractual thing from changing labels, or was it the band’s way of cutting ties and starting fresh?

I guess a bit of both, you know? We did the Huang Chung album and got this deluge of, ”Why have you got this ridiculous name that nobody can pronounce?” So we started thinking upon signing to Geffen, ”Maybe we should have a fresh start and find something else.” But we couldn’t come up with anything else, really, so I think it was David Geffen who said, ”Well, why don’t you just spell it like it sounds?” Which was a very pragmatic idea. (Laughs) So that’s what we did, which made nonsense of the name as any kind of Chinese phrase, but it’s what we did, for better or worse.

Yes, I understand the original phrase was intended to mean ”perfect pitch,” but with the change, it, uh, very much wasn’t anymore.

Yeah. (Laughs) I mean, the name is one of those things that’s sort of morphed its way through all kinds of stuff, really. Obviously, with ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight” and ”everybody Wang Chung tonight,” it’s in a way that gets used in all these sorts of cultural applications, so God knows what it means these days. But it’s an interesting name to have chosen…and it’s very interesting what people have done with it. (Laughs)

I’ve been a fan of Points on the Curve since the first time I heard ”Dance Hall Days.” I’m sure you were pleasantly surprised when that record turned out to be a bigger hit than its predecessor.

Yeah. I think we wrote ”Dance Hall Days” when we were still on the Arista deal, actually. I used to do a bit of guitar teaching to keep the wolf from the door back in those days… (Laughs) …and I remember that was a song that I wrote quite quickly and then sort of developing it over a period of time. I played it to Nick, and then everybody we played it to, you could see their eyes go slightly wider… (Laughs) …so it was a bit of a change from the way people looked at us. I don’t know what it was at that time, but people in the business seemed to really hook onto the fact that that was a hit record. So, yeah, it did make a big difference to our whole profile, and it was around that time that we met up with our second manager, David Massey, and he was the guy who said to us, ”You know what? You should ditch this Arista deal and go and sign with an American label, because the way your music sounds, I think you’ve got a better chance in the States.” And he was right about that, I think. It’s hard to explain why that would be, but it’s to do with the way the English scene works, which is very much based around fashion and doing something kind of…I don’t know, it’s that the music is kind of secondary, in a sense, whereas at that time, certainly in the States, people were into music and musicianship, and they got a song like ”Dance Hall Days.” I like to think it’s got a sort of Little Feat resonance. There are various American bands that it’s influenced by that simply wouldn’t work in the UK.

I liken Wang Chung, at least a little bit, to the Fixx, in that they were more popular here than they were in the UK.

Yeah, there’s a definite sort of…I always find it interesting that there are these bands that make it in the States but struggle in the UK. It’s quite often more to do with their fashion sense than their music…but let’s not go into that. (Laughs)

“Don’t Let Go” was also a hit from Points on the Curve. Are there any other songs on the record that you remember fondly and perhaps wish had been pushed as singles?

Well, “Wait” was an important song on that album, and we did try and do a single version of it, but I think it was a bit of an ill-fated attempt. We worked with…what was that guy’s name? Steve Lipson, who was working with Trevor Horn at the time. I remember going into the studio with him and trying to make the beat much more like Iggy Pop’s ”Lust for Life,” but it was more of a Kraftwerk-y thing, and he and I just weren’t seeing eye to eye at all. But ”Wait” was the song that Bill Friedkin was really into when he was making ”To Live and Die in L.A.,” and he was using it as a temp track in the movie. It was that song that had him phone us up and ask if we’d like to do the score for the movie.

Actually, I’d been planning to ask you how you came onboard for that. So he’d been a fan, then?

Yeah, I guess he was into ”Dance Hall Days,” or…I don’t know. Now, Friedman is a big music fan, although these days he’s more into opera than he is into rock n’ roll, I think. He directs a lot of opera now. But, yeah, back then, he was a real music fiend and listened to all kinds of stuff, and I think he must’ve had — as they did in those days — a cassette of Points on the Curve in his car, and he was listening to ”Wait.” Although I don’t really know the history of the thing, I think he must have had somebody in who was a little more traditional to do the score, but then he thought, ”This isn’t working,” and decided that ”Wait” was how he wanted the score to be. He was in that great situation, a rare situation in Hollywood, where he was the boss and could call a shot like that, so he phoned us up and just said as much. Basically, I was spending an afternoon with a friend of mine who I’d been to college with and hadn’t seen since that time, really, so God knows how Billy got the number, but the phone rang in this guy’s flat, and Bill’s secretary was on the phone and said, ”William Friedkin wants to speak to you. He’ll be available in 20 minutes. Can you take the call?” I said, ”Yeah, I guess so!” (Laughs) this friend of mine had to go out…I think he had to do a bit of teaching or something…so I just stayed in his flat and had this however-long conversation with Friedkin where we talked about Wang Chung, music, and this movie he was making. He basically said, ”Look, what I want you to do is go into the studio with your band and jam about an hour’s worth of music, send it over to me, and I’ll cut it into the movie.” And I just got this really clear sense of what he wanted through that conversation…and, also, because he was into ”Wait.” I guess he probably thought that we were a band, but, of course, by the time, it was really just me and Nick! So we rented a studio in London, and I remember the first day we hired this huge gong thing and a whole bunch of percussion stuff and just spent the day sampling things. We had another four or five days booked, and we just recorded all of this music, some of which I’d sort of had on the boil already. The main theme for “City of the Angels,” for one. It was just a really creative time. We just did the music and didn’t look at the movie at all while we were working on that stuff, so a lot of the soundtrack music in that movie is just straight out of our heads, as it were, and nothing to do with trying to synch it to the movie…although, in a quite uncanny way, that opening sequence and the pace of the music and the cutting of the film really does work well together.

To listen to it, it seems almost like a different band than the one that would come to record Mosaic. Was it a conscious decision to go more commercial?

I think To Live and Die in L.A. was this pendulum swing, in a sense. If Huang Chung was predominantly an art-rock kind of thing, then with Points on a Curve, I think we acknowledged the need for certain commercial criteria. After Points on a Curve, I certainly had this sense of wanting to do something more arty again, and To Live and Die in L.A. was perfect for that. I remember at the time that Geffen were not super happy with us for doing it. I didn’t think about this stuff all the time at the time, but they were basically looking at the bottom line. It’s different now, but back then, an art-rock soundtrack album was just not going to sell like an album with obvious hits on it because you wouldn’t get the top-40 radio play. So they were a bit reluctant to let us do it, but David talked them into it. So we did it, and it was exactly as they expected it to be: it got a lot of, shall we say, critical plaudits, but it didn’t have a hit on it. So they were, like, ”You’ve got to shape up.” (Laughs) I do remember this crossroads, where we were, ”Well, do we do another art-for-art’s-sake project and say goodbye to Geffen, or do we toe the line and work with a producer and really try and have a #1 record?” Certainly, Nick and David were very adamant that we had to do that route, and I, uh, could see the sense in that… (Laughs) …so we hired Peter Wolf, who had produced ”We Built This City,” which was not one of my favorite records, but they all seemed to love it. I’m sounding like I’m distancing myself from it, and that’s not right. I was eager to take advantage of the situation that we were carving for ourselves. That was the way the horse was riding.

I’ve always been curious, though, and you kind of touched on this, but was there any point when you were recording where you were, like, ”Wow, really? We’re really going to be this commercial?”

No, I understand what you mean. And I did feel that. ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight,” when we first recorded it as a demo…we released it on one of our hits albums, and it’s kind of slow. Not a ballad, but a medium tempo that’s very Beatles-influenced and a slightly ironic thing. I heard it as more of an ”All You Need Is Love” thing, more whimsical. But Peter’s sense was, ”Oh, no, you’ve got to make it so it’s like a Donna Summer record!” (Laughs) And I was, like, ”Oh, God.” And that whole ”everybody have fun tonight, everybody Wang Chung tonight” was really an ad-lib idea, but that became the focus of the song. But Peter was a great musician to work with. He’d been in Frank Zappa’s band, and he was very much of that L.A. scene and knew all of these great session singers. He hooked us up with Siedah Garrett, who at that time was working with Michael Jackson, and she sang on ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight.” I can remember the vocal sessions for that album being amazing for me as an English guy who really didn’t ever consider himself a singer. Being in the room with all of these talented people was an education…and working with Peter was an education. He’s a very high powered musician and very exacting. Yes, it’s a commercial album, but it’s got some pretty intricate music on there as well.

The band was also still contributing to the occasional soundtrack as well. It wasn’t too long before Mosaic that you provided ”Fire in the Twilight” to the hallway sequence in ”The Breakfast Club.”

That’s right! Yeah, that came up right after To Live and Die in L.A., I think, and we did that as a one-off thing with Keith Forsey, who was Billy Idol’s drummer and producer. He produced that track and wrote it. In fact, I’ve been rehearsing today, actually, our first rehearsal up in London, and we’ve been routining that track. It’s been quite fun to revisit it in a 21st century way.

When you released Warmer Side of Cool, I was working in a record store at the time, and I remember cranking ”Praying to a New God.” I still view it as a great, terribly underrated single. I would have to guess that you were disappointed by the reception to that album.

Yeah, I guess so, although I think…you know, Nick and I were definitely pulling apart through the making of that album. This pendulum swing I talked about, the art-rock thing is more my bag, I suppose, whereas Nick is more entrepreneurial, shall we say… (Laughs) …so there was a sort of tension there. Peter produced Warmer Side of Cool as well, and I think he struggled to get us to come together and do that sort of positive stuff that we did on Mosaic. With Nick and me, there’s a way for us to work together where the two sides of us really adds up to something pretty good, and there’s a way for us to work where the two sides are quite destructive. I must say that, listening back on various occasions, like when we’ve done a greatest-hits package or have been thinking about remastering things, I’ve found Warmer Side of Cool a difficult album to listen to. It’s kind of overblown, and there were things that Geffen was really turned off by at the time. I think we were slightly…I think we had gone into our Wang Chung bubble a little too far. We weren’t relenting to the way things were going in the outside world.

I’d wondered how much Geffen was needling you with, ”C’mon, boys, we really need another Everybody Have Fun Tonight’!”

Well, absolutely there was that. I think every band and every record label that’s had that relationship wants ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight 2.” Or in our case, it was wanting another ”Dance Hall Days” and then another ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight.” For whatever reason, that pendulum swing makes it…for me, at least…very hard to replicate those things. In fact, very hard full stop to write another ”Dance Hall Days.” Believe me, these days, I would love to do that! (Laughs) I guess if you could bottle all that stuff, you would, but… (Trails off) But, yeah, you have to deal with that as an artist, and I don’t want to sound too pretentious with this, but you do want to keep moving forward, and it’s hard to go back. But the record company has the commercial desire to want to keep replicating the same old trick every time, and that creates a tension. Most bands come up against that, I think, and I think most bands flounder with that at some point. Some of the great bands, of course, manage to reinvent themselves beyond all that stuff.

During Wang Chung’s hiatus after Warmer Side of Cool, you recorded a solo album for Sony that the label promptly shelved without releasing. Are you in a position where you can self-release The Anatomy Lesson, or do they still own it?

I guess Sony owns the masters still. I’ve never approached them about getting that stuff back. I do have the original demos for it, which are pretty high quality, actually, so that’s something I’ll address at some point when I’ve got a bit of time with all of that stuff. Yeah, I’d love to get that album out, kind of in the way that I recorded it, as opposed to cannibalizing the songs and trying to do something new with them. I think I’d prefer to try and release it as a sort of period piece. (Laughs)

I’d be very curious to hear it. I’ve read of its existence, but that’s the extent of my knowledge about it.

Well, in a way, it’s a step on from Warmer Side of Cool, which may be a real turn-off for some people… (Laughs) …but I think it’s an album where I said, ”Let’s pull out all the stops.” I wrote a big ballad and some songs that are almost prog-rock kind of stuff, looking back on it now. Yeah, there’s some good stuff on it, so it’ll be nice to revisit that and try to put it out at some point.

Speaking of prog-rock, you did the Strictly, Inc. album with Tony Banks. That’s another one I’ve never heard, as it never came out in the States, but how did that collaboration come about, and how do you feel about the resulting album?

Well, the guy who did my Anatomy Lesson record was Nick Davis, and Nick was doing…and still does…all of the Genesis albums, most recently working on all the 5.1 re-mastering of the records. Tony decided he wanted to do a solo record and was casting around for a singer, and Nick said, ”Well, try Jack!” And we met up, and, yeah, we sort of hit it off, actually. I still hang out with Tony, still see him. I saw him last year, actually. His wife was celebrating her birthday in Venice, and coincidentally Mel and I were going over there, as it’s our favorite place to go, so we had a really nice time over there. Also, Tony and I are sort of involved with a very curious, almost impossible to explain project… (Laughs) …with a guy who lives about five miles where I live, down here in Canterbury. He’s a very eccentric guy who builds musical instruments, and he’s built this incredible thing that’s…God, I’m starting to try and tell you about it now, but it’s a Victorian barrel harp, if that makes any sense to you. It’s a machine with a rotating barrel with pins sticking out of it, and the pins pluck this almost vertically-suspended piano frame thing, and then the pins…you program it to play different tunes. It’s a weird mixture of 19th century and 21st century, really. But Tony and I have been helping Henry out with a project, so I do still see him reasonably often, and we try to go to concerts in London together and stuff…but I’m way off the point. (Laughs) With Strictly, Inc., Tony was looking for a singer, and I was very flattered to be asked to do it. I was a big Genesis fan…well, a big early Genesis fan, at least…and grew up with Foxtrot and Selling England by the Pound and all those records. It gave me a real insight into those things, working with Tony, but, of course, he’s all very nonchalant about all that stuff now. I was saying to him, ”C’mon, we should get the Mellotron out, and we should get all that old gear out,” and he was, like, ”Oh, I can’t bear to drag that stuff out. We should just use the samples.” (Laughs) But it was a fun record to do.

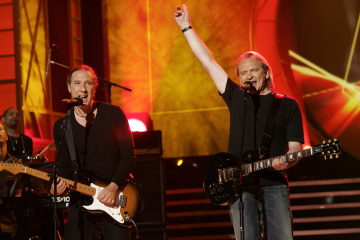

Okay, we’re slowly but surely working our way up to present day, so I guess we should keep moving. You guys had the Wang Chung best-of in 1997, and you and Nick recorded a new single for it (”Space Junk”), but then you toured for a little while as Wang Chung without Nick. What was the impetus for reuniting again in 2005?

Well, it was that TV show, ”Hit Me, Baby, One More Time,” but it was kind of a mixture of things. Nick was working in A&R from the mid-90s through to about that time, and then with all of the meltdown in the record industry, he quit that job and got into doing a bit of managing and stuff. But I think the ”Hit Me, Baby” experience for him was, like, ”Wow, there really is this warmth and enthusiasm for Wang Chung in the States!” And I think we just enjoyed that. We enjoyed spending the time together, and I think that…Wang Chung is quite an interesting little laboratory. (Laughs) Used in the right way, it can be a real fun thing to be doing. From there, we starting thinking, ”Well, c’mon, we’ve got all of these songs lying around, some from the dim and distant past and some more contemporary stuff, so why don’t we get it together and do a new album?” Also, around that time, we signed a new publishing deal as well, with this great company called Spirit Music Publishing, and they were very keen for us to do some new stuff as well. So it’s as if the stage was set already, and all we had to do was walk onto it and try to do something great. (Laughs) So that’s what we’re trying to do!

Do you remember whose idea it was to cover Nelly’s ”Hot In Herre” for ”Hit Me, Baby”?

It was Chris Hughes’, actually. Chris produced ”Dance Hall Days,” and he’s a dear, dear friend of mine who I’ve been close to ever since that time. I have a…well, I call it a jazz project, but in a way it’s more of a prog project… (Laughs) …that I have here in Canterbury called The Quartet, and The Quartet has put out two albums on Chris’s label, Helium, so I’ve been spending quite a bit of time down in Bath, where Chris has his studio, doing these Quartet records. When ”Hit Me, Baby” came up, I said, ”Look, there’s this list of eight songs,” and I think Britney Spears’ ”Toxic” was one of them, along with a bunch of other things, but he said, ”Oh, you should do Hot in Herre,’ you’d do that brilliantly.” And I said, ”Are you serious?” He said, ”Go on, give it a try.” So I basically did it here at home. I got some stuff together, figured out a version of it, and…again, it’s one of those things where it felt like the time was right and everything fell into place. I kind of like that track, actually. (Laughs)

And, now, Wang Chung has the new EP, Abducted by the 80s, and you’ve got the single, “Rent Free,” available through your Facebook page, but with the title track…I have to feel that, with a title like that, some people will say, ”Well, that’s a bit on-the-nose, isn’t it?”

(Laughs) Well, I’m not quite sure you mean by that, but as a song, it’s kind of a weird track. What I love about the current state of play is that, yeah, we can put that out ourselves, and there isn’t a record label going, ”Are you guys crazy? You need a hit single that sounds like everybody else!” So I felt like, ”Yeah, let’s do that!” There are going to be people who are really into it, and people who really aren’t into it, but that’s still great. We’re releasing this double EP that’ll have four re-records of some of the old tracks. We’ve re-recorded ”Everybody Have Fun Tonight,” ”Dance Hall Days,” ”Let’s Go,” and an acoustic version of “To Live and Die in L.A..” That’s on the first EP, and then the second EP has four brand new tracks on it. That’s going to be available in the shops, as it were, from August 9th, I think. But out on tour, we’ve got a bunch of CDs that we’ve had pressed up, and we’re going to be selling them to the fans in kind of an exclusive-preview way. Then the plan is to release another EP in September of four new songs, and then just before Christmas, we’ll release another four. Hopefully, we’ll then scale up the whole thing, and early next year we’ll release a formal album which will have those tracks on it, maybe, plus three or four more extra tracks as well. Doing it through this digital route, the way is to sort of leak it out through small runs of things and make it collectable and have it appeal to those core fans who’ve been with us through all that time, then hopefully spread out into the wider cyberspace fandom that’s available to us.

Lastly, do you have a favorite use of ”everybody Wang Chung tonight” as a pop-culture punchline?

(Laughs) My favorite is from ”The Simpsons,” probably. That’s just great. If you look at our website, which I’m sure you have, there’s a whole sequence of stuff, but I just love that fast cut to Homer, sitting on the couch after he’s been uprooted from his bed for saying that women are inferior. It’s very, very funny. Yeah, I love it that people use that ”Wang Chung” line whenever they can.

Have you always had a sense of humor about it, though?

I think so, yeah. I think of myself as a musician primarily, and I think one of the things that I liked about the name ”Wang Chung” was that it didn’t have a meaning. Of course, it has the Chinese words to it, but it was more just like a sound, and that appealed to me, that you could have a name that was just a sound and didn’t have a meaning, much like you can have a C-chord or a G7-chord. They don’t have a meaning, they just have a sound. That was the original intention. Through the spelling changes and the reckless self-exploration of putting it in a song, Wang Chung has kind of gained this life of its own, but I’ve found I quite like the idea of having a name that may enter the dictionary at some point. (Laughs) That’ll probably be our greatest achievement.

Comments