I’ve looked at some films in this series that are truly bad. But when it comes to writing about the ”worst Best Pictures,” it’s less to do with the quality of the film and more to do with the fact AMPAS’ choice seems ludicrous in retrospect. How Green Was My Valley isn’t a bad movie, but compared to Citizen Kane it may as well be The Room.

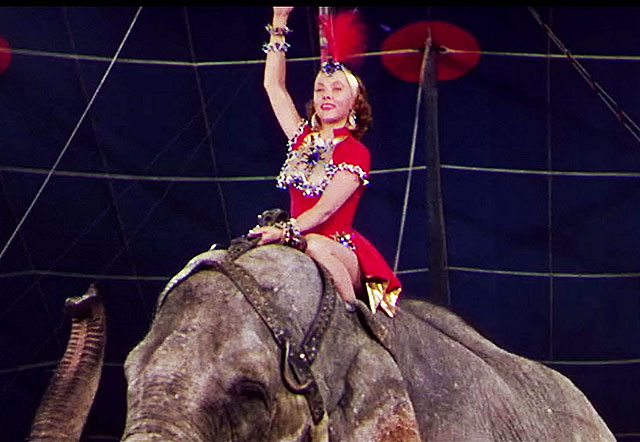

But there are a few Best Picture winners that almost everyone agrees are not just bad decisions, but wretched acts of filmmaking. This month, we’re talking about one of them, Cecil B DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth. The movie famously beat the classic High Noon for the top prize and, while it made a lot of money, frequently is listed as the ”worst” Best Picture and is one of only three winners to have a negative score on Rotten Tomatoes.

In classic Hollywood, DeMille commanded a level of fame few of his peers did. He was an equal draw to his stars and his epics remain some of the highest grossing films ever made. At a time when it was common for directors to be replaced (The Wizard of Oz went through four), DeMille frequently overruled his producers and had enough clout to make what he wanted to make.

But time has not been kind to DeMille’s reputation. Yes, The Ten Commandments remains an Easter staple on U.S. television, but when European critics started discussing the auteur theory (which helped launch the French New Wave and later New Hollywood) in the 1950s and 1960s, DeMille was considered too unsophisticated to be discussed. Other directors hated him and critics frequently didn’t like his films. When Sight and Sound put together their most recent ”best of” list in 2012, The Ten Commandments, his famous version of Cleopatra, and this film were all excluded.

How can someone who used to be one of the most famous directors on the planet be so forgotten? Well, judging by this film, it’s because he’s not a very good storyteller and as grand as his movies are, they don’t have much substance. Besides, their sensibilities are far too dated and some of his filmmaking decisions are baffling.

Let’s start with its outdated sensibilities. The film was made in partnership with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Baily Circus — a company that went defunct four years ago. While circuses and traveling carnivals used to be an important part of American entertainment, they were a joke for decades and popular media doesn’t take them seriously anymore. Yes, The Greatest Showman was popular with audiences but even that had to play up the corny reputation circuses have long held to connect with its audiences. It says something that Tod Browning’s Freaks is in the National Film Registry but this movie is, as I write this, not.

But even beyond its outdated subject matter, the film’s story is riddled with cliches and poorly thought-out characters. The main character is Brad (Charlton Heston), the circus manager who is trying to ensure that his circus has a ”full season.” He does this by recruiting master trapeze artist The Great Sebastian (Cornel Wilde) and puts him in the center ring at the expense of Holly (Betty Hutton), who has romantic feelings for Brad. However, while they initially try to compete, Sebastian ends up seducing Holly before tragedy befalls him. Also, Gloria Grahame plays another performer in the circus and James Stewart shows up as Buttons the Clown, a man with a mysterious past.

Something interesting COULD be done with this material, particularly if the film pointed out the absurdity of how these world class athletes are forced to perform under a tent. The worst thing to do would be to play it straight — but that’s exactly what DeMille does. The film is also part documentary, as DeMille walks us through how the circus moves from one town to another and acts like the erection of the big top is the creation of the eighth wonder of the world. Sebastian is treated like a movie star. The circus is always filled and is treated as the most important thing in whatever town they’re in. Was that ever the case after 1939?

The characters are also poorly written. At times I felt like I was watching a soap opera. Sebastian is as much a caricature of the French as Pepe LePew. They even have similar voices. He exists to hit on women, be a trapeze artist and…that’s it. We don’t learn much about him, like why he became a circus performer and how he became a superstar. We also don’t know why Holly eventually falls for him and what he sees in her beyond just another fling.

That’s not even getting into the main character, Brad. We know nothing about how he joined the circus and what drives him. He’s played as a sort of Indiana Jones-esque hero, minus the action and the enemies. We know he hates crooked carnies and is very protective of his performers. But why? Ultimately, he’s just running a circus, but he acts like he’s helping plan the Normandy landings. Does he care about anything beyond the big top? The women in his employ complain that he doesn’t let anyone in. This is true but having a character comment on it only emphasizes the flaws in the character. This is supposed to be our way of understanding why the circus is so important. But with a character this aloof, that task becomes impossible. Even when he’s injured when the circus train derails in the third act, there’s no drama. By that point I found myself incapable of feeling any sympathy for him and didn’t think of it as a human tragedy but as a way for DeMille to create action in a film that has very little.

This scene also reminds me of how padded movie is. This movie runs more than two and a half hours but only has an hour’s worth of plot. How does DeMille do it? By padding it with his documentary scenes and having characters repeat the same thing. Three different performers as Heston if they’re going to have a ”full season” this year in the span of five minutes. There’s a parade sequence that lasts a good twenty minutes, with acts around a theme like Disney characters (I assume this was before the company became one of the most litigious forces on the planet) and ”A gay 90s album” (which surprisingly isn’t a Melissa Etheridge album). It’s completely pointless to the narrative and, to make matters worse, the scene constantly cuts back to an audience member saying who the costumed characters are. (He’s apparently a big fan of the Mad Hatter.) Who is he? Why do we need him explaining the parade when the ringmaster is already doing so? What does this man have to say about how circuses entertain audiences?

You know who should have directed this material? Fellini. He has enough respect for clowns and the circus as well as the ability to recognize how weird the spectacle is. Indeed, he made a film for Italian TV about clowns and why people are so interested in them. One of his most famous characters, Cabiria, may as well be a clown with the way she dresses and acts. I haven’t seen the former film, but I imagine he embraced the absurdity of people putting on grotesque makeup in order to be ”funny.” Indeed, 8 ½ famously ends with a parade and, despite the scene’s length, it’s a brilliant reflection on the main character’s obsessions and the people in his life. I desperately wanted that parade to replace the one in this movie. It meant something to the characters. It wowed its audience. DeMille didn’t care about his characters the way Fellini did, so his spectacle is hollow.

Yet the biggest flaw of all is that this movie completely ignores what was happening in our world. What I mean is that the 1950s movies that have remained in the public conscious responded to what was happening at the time, from the beginnings of the Cold War to HUAC to examinations of a post war America and how people were responding to the new, conservative normal. There are some great ones, like Bigger than Life, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Them. There were even some films that took existing popular genres and remade them to reflect 50s sentiments, like how Kiss Me Deadly took film noir and infused it with nuclear paranoia or how 12 Angry Men used courtroom drama to confront racial bias and segregation. The Greatest Show on Earth does none of that. It feels hopelessly dated, even by 1950s standards. Sure, circuses were still around, and audiences wanted simple entertainment. But it’s not like time was standing still. How was something like a circus competing with the rise of television, which brought spectacles like this into people’s homes? Why not make Buttons, the man on the run, someone who is hiding due to his past communist affiliations? Yet the film pretends like this circus is the only thing in the world. And we know now how wrong that sensibility is.

The Greatest Show on Earth is bad. It’s dated, its characters belong in a soap opera, it’s too long, and it’s pointless. This was nothing but a Ringling Bros commercial that happens to have a giant Hollywood production behind it. That could serve as a useful time capsule, but the film doesn’t do anything to explore circus culture and circus performers. Its tone and themes could apply to any form of entertainment — Brad may as well be a movie director or a music producer. The only thing that makes this movie about circus culture is its documentary scenes, which are so melodramatic I’m not sure they weren’t meant to be funny. In fact, this would have been better as a surrealist comedy where someone pointed out the ridiculousness of the circus culture and how these performers were sacrificing themselves for a brief thrill for the audience. Other movies and TV shows have explored circus culture in a more satisfying way, like Freaks.

But why did this win Best Picture? It was possibly an honorary award for DeMille. It’s also likely the always conservative AMPAS didn’t want to ruffle feathers by selecting High Noon and standing up against HUAC. But their decision didn’t save their reputation in this case. Now that HUAC is viewed as a dark stain on American history, AMPAS’ decision to not stand up against it looks that much worse. And the fact they selected this film as a ”Best Picture” of any year makes them look downright crazy. I’m in favor of paying tribute to industry veterans, but awarding this movie Best Picture seems like it was done out of pity.

Comments