”Why are we willing to pay for computers, iPods, smart phones, data plans, and high speed internet access but not the music itself?”

— David Lowery

”But I honestly don’t think my peers and I will ever pay for albums. I do think we will pay for convenience.”

— Emily White

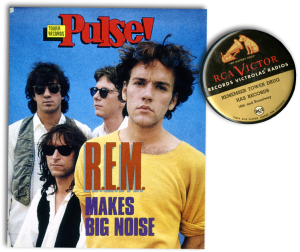

“No Music, No Life”

–Tower Records

A blog post by Emily White (a 21 year old intern at NPR), and the reaction by David Lowery (Camper Van Beethoven/ Cracker) has become quite the generational divide when it comes to the business of music. The economics of the music business — even to this outsider whose education about the business is gleaned by articles, some books, and many viewings of VH1’s ”Behind the Music” — is clearly one that rewards the few, but for a time, made it possible for the many to eek out a living doing what they love.

And then came the Internet and file-sharing…

When Napster, Kazaa, Limewire, and a number of other sites allowed people to download mp3s (a format that’s convenient for file-sharing and loading up your iPod, but horrible for audio fidelity) for free, the floodgates opened for causal music consumers to expand their library without dropping any additional coin from their bank accounts. At the time, the attitude toward downloading music for free went something like this: ”Man, I pay $12.99 to $18.99 for a CD and there’s maybe one or two good songs on them. CDs have been out since the 80s and they have never gone down in price. In fact, they are going up in price and the quality of the music we’re being asked to pay for is for shit. So if I can get the songs I want for free, I think it’s justice for all those years I’ve been paying for expensive CDs and not getting value for my money.” In short, illegal downloading was a revolt of the consumers who felt the record companies were ripping them off at the cash register. And you know what? I’m totally guilty of grabbing free to low cost mp3s (and offering it on my blog and here at Popdose). My agenda, though, was not to make a buck (I never did), but rather share my enthusiasm for a band or artist by showcasing a song (or six — in the case of the feature I used to write every week here at Popdose). I wanted to remind people of the greatness of a song or artist and motivate them to buy the music through a legitimate music service (which is why links to Amazon or iTunes were included). Did it work? For a minority of readers, yes. But the vast majority just wanted their free mp3s. Alas, the initial rebellion of consumers against the record labels turned into an addiction to free.

file-sharing and loading up your iPod, but horrible for audio fidelity) for free, the floodgates opened for causal music consumers to expand their library without dropping any additional coin from their bank accounts. At the time, the attitude toward downloading music for free went something like this: ”Man, I pay $12.99 to $18.99 for a CD and there’s maybe one or two good songs on them. CDs have been out since the 80s and they have never gone down in price. In fact, they are going up in price and the quality of the music we’re being asked to pay for is for shit. So if I can get the songs I want for free, I think it’s justice for all those years I’ve been paying for expensive CDs and not getting value for my money.” In short, illegal downloading was a revolt of the consumers who felt the record companies were ripping them off at the cash register. And you know what? I’m totally guilty of grabbing free to low cost mp3s (and offering it on my blog and here at Popdose). My agenda, though, was not to make a buck (I never did), but rather share my enthusiasm for a band or artist by showcasing a song (or six — in the case of the feature I used to write every week here at Popdose). I wanted to remind people of the greatness of a song or artist and motivate them to buy the music through a legitimate music service (which is why links to Amazon or iTunes were included). Did it work? For a minority of readers, yes. But the vast majority just wanted their free mp3s. Alas, the initial rebellion of consumers against the record labels turned into an addiction to free.

And that rebellion had an effect that we clearly see today: the dominance of digital downloading (whether it’s through Amazon, iTunes, or freebiemp3) has created a generation who has been socialized to view music as a product that should not be paid for. Who has that hurt? Well, there are only a handful of major music labels left, the number of artists who make a living at music (according to David Lowery) has fallen 25% since 2000, the CD is almost dead as a format, people spend less of their income on music, commercial radio stations won’t play ”proven” hits and have trimmed their play lists to around 250 songs in rotation, and MTV is a channel that has very little to do with music. Talk about a recession! But missing on that list are record stores. You know, those brick and mortar entities that actually employed people to market and sell records to the general public.

Many regions in the country have (or had) record stores that where a lot like the one featured in the book and movie, High Fidelity. Those places, however, were usually located in urban areas where coolness seemed to abound. But I grew up in the suburbs of the Bay Area and the one place where I could find an impressive collection of music was Tower Records. Started in 1960 in Sacramento by Russ Solomon, Tower was a place that not only sold records, but at the time I was a frequent customer, videos, books, and magazines as well.

Many regions in the country have (or had) record stores that where a lot like the one featured in the book and movie, High Fidelity. Those places, however, were usually located in urban areas where coolness seemed to abound. But I grew up in the suburbs of the Bay Area and the one place where I could find an impressive collection of music was Tower Records. Started in 1960 in Sacramento by Russ Solomon, Tower was a place that not only sold records, but at the time I was a frequent customer, videos, books, and magazines as well.

Even though I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, the suburbs in the early/mid-80s were a fairly backwater place when it came to cultural consumption. Tower Records, however, was one place I was able to browse interesting books, unique magazines, and sift through the racks of albums looking for enticing artists to listen to. To me, it was a kind of oasis in a cultural flatland.

But my little Shangri-La in the burbs wasn’t always an ideal place to spend my off hours every week. For example, the employees weren’t always the most helpful (I had a couple of friends who worked there, and one of them said to me half-jokingly: ” The customer is the enemy’ is the motto at Tower.” ) Sometimes that was clearly the case. When the Sugarcubes released their first album (which MTV was saying was the ”best album of all time”) I was at the San Francisco Tower Records (on Bay and Columbus) and they were playing ”Birthday.” I went to the counter and asked if that was the Sugarcubes playing over the house speakers, and clerk just rolled his eyes, huffed, and hissed a ”yesssssss.” I asked if I could find the album in the rock category or if it was an import. He just pointed to the stack of albums at the front of the store where the new releases were. I quickly ducked away, got the albums I was there for, paid for them and went home to experience this so-called ”best album of all time.”

Sure, the clerk was an asshole about my questions, but that was part of the Tower culture. Some of the clerks were music snobs (or just had big egos), but the majority of them were cool once you got to know them. Sometimes there was an elitist judgment about purchases when paying at the cash register, but mostly these were music fans that loved being around the physical products artists created. That enthusiasm, deep knowledge, and, yes, snobbery about music helped me in my own musical education. If it weren’t for stores like Tower Records, I wouldn’t have been exposed to some jazz artists, classical music, soundtracks, comedy albums, and compilations that had rare recordings. Also, if there wasn’t a place where I could spend a few hours just browsing, talking to the staff, leafing through music magazines with friends, I don’t think my love of music would have been as deep.

You see, the record store was more than just a place where you could buy physical copies of recordings, or a place where you  could read liner notes on the back of an album (if that’s where they were printed), they were places where you received your music education from people who made their living selling this stuff. Even in our highly connected world, the power of a face to face interaction with people who know more than you about music has a deeper effect than a thumbs up on You Tube, a Like on Facebook, or a favorite Tweet. Launching the iTunes store or buying mp3s from Amazon is certainly convenient, but what made a visit to Tower so special is that you had to make an effort to get there, have a list (if you couldn’t remember what you were looking for) and then pull out actual cash and slap it down on the counter in order to experience the music. Plus, if you didn’t have a cassette or CD player in your car, you had to wait to listen to the album when you got home. That process builds anticipation — which in turn makes what you purchased valuable. Sure, I was working in radio at the time I was a frequent customer at Tower Records, and I got some promo copies of albums and singles, but when I bought the music, I savored it more. I treated my albums with a lot of care. Yes, I made cassette copies so I wouldn’t wear out the vinyl, but my music collection I was something I built out of love for the art form, the artists who created the music, and the pleasure of listening to the songs. Building that collection took time, money, and effort, and having a place like Tower where I could buy music by artists that I read about in BAM!, Pulse, Rolling Stone, Spin, NME, and many of the other publications was part of the reason why records stores like Tower were such an important part of my life. It was an investment I was making in something I valued. I didn’t understand the economics of the music business back then, but I knew that the money I spent at Tower (and other record stores) went to pay the staff at the store, the labels, and, yes, the artists who created that music. It wasn’t hard to see the effect spending money on records had on my friends. It kept them employed.

could read liner notes on the back of an album (if that’s where they were printed), they were places where you received your music education from people who made their living selling this stuff. Even in our highly connected world, the power of a face to face interaction with people who know more than you about music has a deeper effect than a thumbs up on You Tube, a Like on Facebook, or a favorite Tweet. Launching the iTunes store or buying mp3s from Amazon is certainly convenient, but what made a visit to Tower so special is that you had to make an effort to get there, have a list (if you couldn’t remember what you were looking for) and then pull out actual cash and slap it down on the counter in order to experience the music. Plus, if you didn’t have a cassette or CD player in your car, you had to wait to listen to the album when you got home. That process builds anticipation — which in turn makes what you purchased valuable. Sure, I was working in radio at the time I was a frequent customer at Tower Records, and I got some promo copies of albums and singles, but when I bought the music, I savored it more. I treated my albums with a lot of care. Yes, I made cassette copies so I wouldn’t wear out the vinyl, but my music collection I was something I built out of love for the art form, the artists who created the music, and the pleasure of listening to the songs. Building that collection took time, money, and effort, and having a place like Tower where I could buy music by artists that I read about in BAM!, Pulse, Rolling Stone, Spin, NME, and many of the other publications was part of the reason why records stores like Tower were such an important part of my life. It was an investment I was making in something I valued. I didn’t understand the economics of the music business back then, but I knew that the money I spent at Tower (and other record stores) went to pay the staff at the store, the labels, and, yes, the artists who created that music. It wasn’t hard to see the effect spending money on records had on my friends. It kept them employed.

Plus, if you had an interest in the music business, you could get your start at a record store. If you were in a band, a record store like Tower could help you sell your LP or EP by putting your DIY record next to an established artist — which, by association, had a certain level of ”Look Ma! I’ve got a record that’s next to The Rolling Stones!” prestige. There were also in-store appearances by bands who would play a few songs, sign autographs — usually on the albums fans bought at the store —and do their part to stimulate the local economy and their own livelihood. This, children of the I Will Never Pay For Music culture, is what made that part of the economy run and allowed people who didn’t want to be day traders, office drones, lawyers, or computer programmers work in an area where their passion for the art form allowed them to live.

So when folks like me get accused for being nostalgic for record stores, physical copies of LPs, CDs, and maybe even cassettes, there’s certainly a sense of loss for a place where one could hang out til midnight and be surrounded by music lovers. But there’s the hard reality that if you don’t pay for music and expect it to be free for consumption, artists will eventually stop making music and suffer the same fate as Tower Records did. Or, as David Lowery, said in his reply to Emily White: ”Congratulations, your generation is the first generation in history to rebel by unsticking it to the man and instead sticking it to the weirdo freak musicians!

While Tower Records may never come back as a physical store, you can support the Tower Records Archive Project and preserve an important part of music culture for people to remember.

Comments