Right off the bat, I’ll admit that I’m not a Christmas person. This season full of earwig songs, clashing colors and increasingly unnecessary shopping frenzy leaves me cold. That said, I’m a staunch defender of Love Actually, the 2003 parade of rom-com conventions that writer/director Richard Curtis almost certainly intended to become a Christmas classic. Through a dizzying combination of earnestness and parody, Love Actually transcends everything that should make it an insufferable slog. Or at least that’s the way I see it. The film has a reputation that is divisive at best. I’m here to stand for its merits in spite of its obvious flaws.

The beauty of Love Actually begins and ends with Curtis’s dedication to well-worn tropes of romantic comedy. Few of the storylets that make up the film’s bald-faced tapestry diverge from cliche, but that’s part of the fun. Pretty much any of the individual “movies” within the movie would be awful as a stand-alone feature, but the fact that few of them occupy more than 10-15 minutes of actual screen time renders them palatable and even enjoyable. We don’t have to sit through the interminable middle bits that pad out most rote love stories, only the essential scenes of each. The result is an unbroken procession of memorable moments and sharp lines. Sure, none of the characters are especially deep, but then they wouldn’t be in a stand-alone movie anyway.

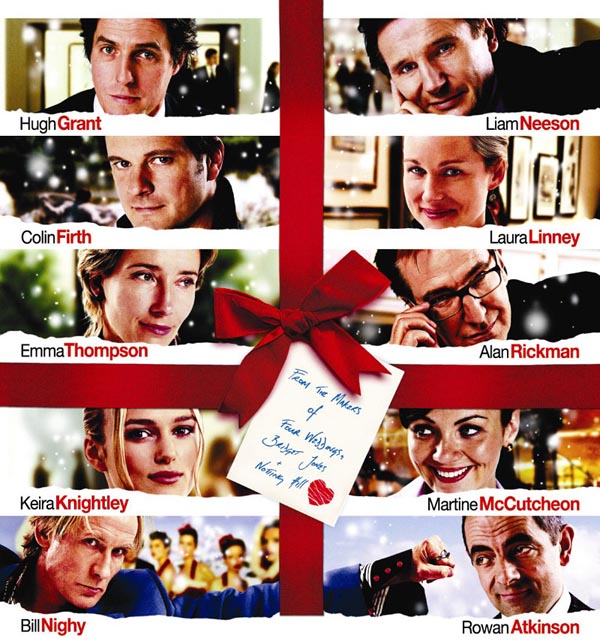

It also helps that the cast is so game throughout. Whereas the typical romantic comedy is populated by flavor-of-the-month actors or familiar faces blatantly pursuing an easy paycheck, Love Actually makes the most of a fun ensemble. Liam Neeson gets to be tragic and fatherly, Hugh Grant gets to be exceedingly British, Alan Rickman gets to go dark and Laura Linney gets to be comically frazzled. None of the cast play against type, but the end result is like seeing a showcase of why we like these performers in the first place. Really, who wants Colin Firth to show up and not play the guy who hides a deep well of emotion beneath a cripplingly reserved exterior? Like a box of assorted chocolates, the ensemble is satisfying precisely because their performances are familiar. There’s nothing bold or unusual in the offing, all the better for a collection of sweet things.

What’s most important (at least to me) about the success of Love Actually is that it’s not all happy endings. This is the mistake Garry Marshall continues to make with his cheap knock-offs of the LA rom-com tapestry model. The likes of Valentine’s Day and New Year’s Eve send their broad collection of archetypes hurtling inextricably toward the best of all possible conclusions. In a format that is already inherently false, these closing cavalcades of happy ring hollow. Love Actually is about 60/40 happy-to-sad by film’s end, though one of the “happy” endings (Kris Marshall’s absurdist sex comedy visit to America) is mostly a parody to begin with, dropping the ratio to a more or less even split between happily ever after and sadly surviving. All the while, the sad bits don’t come off as manipulative. They don’t exist purely to elevate the happy moments, but to create a full spectrum that places the varying emotional notes in context.

And as for why Love Actually also succeeds as a Christmas movie, it’s all about framework vs. message. The worst Christmas movies suggest or outright say that the holiday has some inherent meaning, then attempt to impose that meaning on reality. They’re treacly message movies about charity, family unity or faith. That, or wantonly ironic wallows that use the cheery yuletide atmosphere to drive home as much pain as possible. The truth is, Christmas (or any holiday) isn’t about one thing. Rather, it’s a period of heightened emotions full of memories, hopes and self-reflection. Love Actually uses the intensifying properties of Christmas to add urgency and even believability to its many romantic comedies, never really commenting on what Christmas itself is supposed to mean.

So, while I’m happy to avoid any version of Miracle on 34th Street, eager to shoot down the glib treatment of fairly serious subject matter in It’s A Wonderful Life and quick to cringe every time Linus trots out his churchy monologue at the end of the otherwise inoffensive A Charlie Brown Christmas, I’ll gladly admit to having a soft spot for Love Actually. When the jingle bells start ringing, I’m always compelled to drag out that old DVD, caught somewhere between the guilty pleasure of rom-com dim-sum and a surprisingly masterful work of cinema.

Comments