For the first time in a generation, my Ventura County, CA, congressional district will receive new representation, and the race’s unique contours have drawn the eyes of the nation. This series explores the local, statewide and national ramifications of a race that just might change the composition of the next Congress, and even might help transform the way we choose our leaders. I outlined the parameters of the race here. I interviewed the independent candidate, Linda Parks, whose candidacy has drawn nationwide attention and a million dollars in attacks. I explored the ways in which debates bring out the best and worst in our politicians and ourselves. And I detailed the desperate and disillusioning behavior of local and national Democrats as they have attempted to ensure a spot on the November ballot for their preferred candidate, Julia Brownley.

As the congressional race in my home district, California 26, careens toward Tuesday’s primary election, this is as good a time as any to take a step back and assess the ways in which the state’s new, nonpartisan redistricting and its first ever open-primary campaign have transformed our politics — and the ways in which they have not. With four days left before the district’s voters go to the polls, our little race has left the local and national Democratic Party in an ugly panic, local Republicans bizarrely (and perhaps mistakenly) complacent … and an independent candidate who has become a cause celebre for moderates, contrarians and underdog-rooters nationwide, even as her local prospects may have been buried beneath a million-dollar avalanche of negative advertising.

All of this, because Californians once again chose to live up to our reputation as the ”laboratory for democracy” — a laboratory that was built on this 82-word foundation:

”The legislative power of this state shall be vested in a senate and assembly which shall be designated The legislature of the State of California,’ but the people reserve to themselves the power to propose laws and amendments to the constitution, and to adopt or reject the same, at the polls independent of the legislature, and also reserve the power, at their own option, to so adopt or reject any act, or section or part of any act, passed by the legislature.”

— The California state constitution, as amended by Proposition 7, passed in 1911

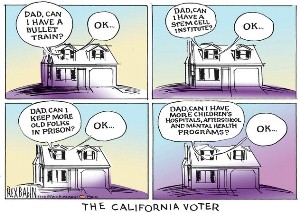

I’ve never thought much of the initiative process in California, or any other state for that matter. Dreamed up a century ago, during the Progressive Era, to give more power to the people, the tradition of creating legislation via ”direct democracy” certainly has left a legacy of laws that reflect the public will. Too bad that will is so extraordinarily fickle and impulsive, so easily manipulated by negative campaigning, and so frequently bone-headed and even immoral. It would be one thing if initiatives were restricted to one area of governance — new taxes and spending, say, or perhaps the rejection of laws passed by the legislature — while the rest of the job of running the state was left to the executive and legislative branches that were … you know … envisioned by the founding fathers to handle this stuff.

I’ve never thought much of the initiative process in California, or any other state for that matter. Dreamed up a century ago, during the Progressive Era, to give more power to the people, the tradition of creating legislation via ”direct democracy” certainly has left a legacy of laws that reflect the public will. Too bad that will is so extraordinarily fickle and impulsive, so easily manipulated by negative campaigning, and so frequently bone-headed and even immoral. It would be one thing if initiatives were restricted to one area of governance — new taxes and spending, say, or perhaps the rejection of laws passed by the legislature — while the rest of the job of running the state was left to the executive and legislative branches that were … you know … envisioned by the founding fathers to handle this stuff.

Instead, these two forums for lawmaking in California and other states have never learned to coexist, while initiatives have been allowed to run amok. They are variously responsible for instituting horrible social policy, often on issues that should never be subject to majority votes in the first place (Prop 8, anyone?); creating laws that contradict each other or are thoroughly incompatible (occasionally requiring the same revenue to be spent several different ways and several times over); and, in the case of the alternately loved and loathed Prop 13, severely curtailing the taxing and spending flexibility of our elected representatives — who, thanks in part to our own drunkenness with the power of the ballot, we no longer respect much anyway.

There’s the irony of the initiatives: Implemented during a time when legislators too rarely were seen as doing the work of the people, and invented with the hope that ”good government” would arise from the people themselves, initiatives more often than not result in government that is truly lousy.

That said, in recent years we Californians — like those of 100 years ago — have been on something of a roll, passing one initiative after another meant to shake up our system of governance. Over the last decade, as discussed previously on this site, we have achieved critical mass in our disgust with the paralysis in Sacramento — for which we ourselves are primarily responsible, thanks to the buildup of farkakta initiatives over the years (Prop 13, term limits, etc.). However, also playing a huge role in the capitol’s permanent stalemate is the grand tradition of legislators gerrymandering themselves into safe districts and then refusing to compromise with the just-as-safe representatives of the other party. And that part of our statewide train wreck, we decided, we would do something about.

That said, in recent years we Californians — like those of 100 years ago — have been on something of a roll, passing one initiative after another meant to shake up our system of governance. Over the last decade, as discussed previously on this site, we have achieved critical mass in our disgust with the paralysis in Sacramento — for which we ourselves are primarily responsible, thanks to the buildup of farkakta initiatives over the years (Prop 13, term limits, etc.). However, also playing a huge role in the capitol’s permanent stalemate is the grand tradition of legislators gerrymandering themselves into safe districts and then refusing to compromise with the just-as-safe representatives of the other party. And that part of our statewide train wreck, we decided, we would do something about.

We were spurred on by our former Governator, Ahnold Schvartzenaygah, who was elected as a Republican (in a recall election, another product of Progressive-Era reforms) but eventually gave up on the recalcitrant Cahleyfohnyah GOP and eventually urged voters to put a pox on both parties’ houses. We have acted, admittedly, less with a sense of high-minded civic urgency than with an attitude of ”Fuck it — let’s see if THIS works!” Nevertheless, over the past few election cycles we have wrested control of drawing legislative districts from the rigor-mortised hands of those lawmakers, and we have transformed our elections system to mute, at least to some extent, the dominance of parties and ideology in our politics.

We accomplished the latter by signing on to the ”open primary” system, derived from European-style runoff elections. Beginning with this year’s primary season, which concludes on Tuesday, candidates for state and federal offices are thrown into a single, omnibus primary — with voters no longer being handed Democratic or Republican ballots based on their registrations. And the top two vote-getters, regardless of party, go on to face each other in the general election. If two Democrats (or two Republicans) finish atop the primary results in a district, the other party is simply out of luck come November. It’s a shift that foments a welcome uncertainty in the early stages of campaigns; that forces even entrenched incumbents to launch their campaigns early and turn out their supporters in the primary; and that encourages moderates who can pull votes from both parties, as opposed to the candidates on the ideological extremes who recently have thrived in safe districts across California and other states. It also encourages increased turnout, particularly among independents who traditionally have been left out of the primary season altogether.

The two major parties, of course, hate all these changes, and tried like the dickens to dissuade Californians from voting for them. After all, the parties had spent the last two centuries figuring out how to game the traditional system — how to exercise a measure of control over the selection of their own candidates, how to shut out third-party candidates, and how to retain for themselves, rather than individual office-seekers or even voters, the power to determine the issues over which elections will be fought. Now the parties are no longer assured that their issues will even receive an airing during the general-election campaign, much less that they’ll have a candidate on every ballot line in the state come Novembe 5.

The two major parties, of course, hate all these changes, and tried like the dickens to dissuade Californians from voting for them. After all, the parties had spent the last two centuries figuring out how to game the traditional system — how to exercise a measure of control over the selection of their own candidates, how to shut out third-party candidates, and how to retain for themselves, rather than individual office-seekers or even voters, the power to determine the issues over which elections will be fought. Now the parties are no longer assured that their issues will even receive an airing during the general-election campaign, much less that they’ll have a candidate on every ballot line in the state come Novembe 5.

Other state and federal primary contests have been transformed by these recent changes — the two old-line Democratic congressmen who have been forced into a death match in the San Fernando Valley, for example, or the moderate Republican in San Diego who bailed on his party mid-race (despite his rising-star status within the GOP) because it makes more sense to run with an (I) next to his name, rather than an (R), against a Tea Party nutcase who has become his local GOP’s flavor of the month.

But nowhere, in California or around the country, is a congressional race considered more potentially transformative than right here in Ventura County, where the popular independent Linda Parks may still push her way past an establishment Democrat and onto the general-election ballot. This election has exposed both the benefits and the deep flaws of the open-primary system, which California is modeling for the nation. And it has served as a primer for both the major parties and for independents everywhere, as they figure out how to deal with rising public anger over entrenched incumbency and hyper-partisanship in capitol buildings across the land. Some of the lessons they’re learning:

1. Independent candidates are now a force to be reckoned with. Win or lose on Tuesday, Parks’ candidacy is going to serve as a model for moderate and nonpartisan office seekers across the state, and perhaps eventually nationwide, as they assess their chances of bucking the major parties’ dominance. In the open-primary system, a well-known, popular local officeholder has every opportunity to succeed in an evenly drawn district like the new CA-26 — or even in a district that tilts so far to one side that an independent might draw more votes than a candidate from the out-of-favor party.

1. Independent candidates are now a force to be reckoned with. Win or lose on Tuesday, Parks’ candidacy is going to serve as a model for moderate and nonpartisan office seekers across the state, and perhaps eventually nationwide, as they assess their chances of bucking the major parties’ dominance. In the open-primary system, a well-known, popular local officeholder has every opportunity to succeed in an evenly drawn district like the new CA-26 — or even in a district that tilts so far to one side that an independent might draw more votes than a candidate from the out-of-favor party.

2. Organize early, and ruthlessly. If there’s one thing the open-primary system demands from the parties, it is discipline — the discipline to coalesce early around a single, viable candidate, and to remove ideologically similar rivals from the race before they find their way onto the ballot. If the Democrats fail to get their preferred candidate, assemblywoman Julia Brownley, through the primary, they will only be able to blame themselves … or, at least, they can blame the three other Democrats who refused to clear the decks, and who may collectively pull enough votes from Brownley to launch Parks toward November.

Of course, for the last 45 years or so the terms ”discipline” and ”Democratic Party” have been mutually exclusive — and Democratic candidates often jump into races like this one because they believe the party’s voters will find their particular issue set, or ethnicity, or built-in constituency attractive enough to build a coalition around. The trouble is, the four Democrats competing in CA-26 are not on a Democratic ballot this Tuesday — they’re on a single ballot with Parks as well as the lone Republican, state senator Tony Strickland. (See how quickly the GOP can coalesce, at least when its establishment candidate is conservative enough to keep the Tea Party at bay?) And there’s a solid chance that not one of those Dems will still be competing a week from today.

It’s ironic, this notion that the parties need to weed out their also-rans even before the voting starts. And it certainly runs counter to the entire purpose of open primaries, which is to encourage more voices in the electoral process, at least in the primary phase, before giving voters a clear two-person choice in the fall. Nevertheless, if the new system results in more independent and third-party candidates who can pull significant votes, then the parties (and their potential office seekers) will need to revise their assumptions about what makes a candidacy worthwhile.

3. Raise lots of money — or make a big stink about NOT raising it. For independent candidates, increased competitiveness will necessitate learning how to gather oodles of money — or else it will require focusing their campaigns on their principled rejection of such fundraising, if not turning that opposition into a cause verging on martyrdom. Parks, who has been outspent about 10-to-1 this spring by Brownley and her PAC/party supporters, plays the no-special-interests card every chance she gets, and is getting a lot of mileage out of it. Of course, as I have noted ad nauseum throughout this series, standing firm in the face of a deluge of outside money is not just a strategy for Parks — it’s a key element in her history, and for years it has been a huge part of her political appeal. Still, she may as well be writing a textbook on contemporary independent campaigning, because other candidates will be following her example well into the future.

4. Don’t expect an end to negative campaigning … or, rather, do expect it. We’ll have a clearer answer to this question on Wednesday morning. Nevertheless, if the great political thinkers who devised the open-primary system had hoped that putting Democrats, Republicans, independents and third parties on the same primary ballot would encourage free-ranging debate and disarm the parties’ attack machines, the race here in CA-26 isn’t offering much cause for optimism. Instead, Brownley and the Democratic Party have treated the race like that bloodbath in the first moments of The Hunger Games — going after the least-funded of their major rivals (Parks) in remarkably unscrupulous and expensive fashion, lying their asses off about her record and her policy positions (in 35 mailers to date, according to the Parks campaign) in order to drive her numbers down. It must have worked, to some extent, though there’s been no recent polling to bear that out. One simply must assume that a million dollars spent on vicious attacks will leave their mark, particularly when Parks is combating their cannons with a slingshot, financially speaking. But an open primary isn’t a zero-sum game with just one victor, the way a traditional intraparty contest or general election is. And it will be interesting to see, in a six-person race from which two will emerge, whether the candidate whose supporters are behind all the negative ads (Brownley) might lose as much (or more) luster by Tuesday as Parks will. Which brings us to…

4. Don’t expect an end to negative campaigning … or, rather, do expect it. We’ll have a clearer answer to this question on Wednesday morning. Nevertheless, if the great political thinkers who devised the open-primary system had hoped that putting Democrats, Republicans, independents and third parties on the same primary ballot would encourage free-ranging debate and disarm the parties’ attack machines, the race here in CA-26 isn’t offering much cause for optimism. Instead, Brownley and the Democratic Party have treated the race like that bloodbath in the first moments of The Hunger Games — going after the least-funded of their major rivals (Parks) in remarkably unscrupulous and expensive fashion, lying their asses off about her record and her policy positions (in 35 mailers to date, according to the Parks campaign) in order to drive her numbers down. It must have worked, to some extent, though there’s been no recent polling to bear that out. One simply must assume that a million dollars spent on vicious attacks will leave their mark, particularly when Parks is combating their cannons with a slingshot, financially speaking. But an open primary isn’t a zero-sum game with just one victor, the way a traditional intraparty contest or general election is. And it will be interesting to see, in a six-person race from which two will emerge, whether the candidate whose supporters are behind all the negative ads (Brownley) might lose as much (or more) luster by Tuesday as Parks will. Which brings us to…

5. Independents can — and should endeavor to — provide ethical ballast in an open primary. This system was designed to encourage ”good government,” and whatever else you might say about disingenuous attack mailers, they’re not ”good.” Brownley’s worst, and most telling, moment of the primary campaign was her inability to join her other rivals in denouncing the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee’s mailers trashing Parks. It was an ugly, uncomfortable scene — mostly because it’s difficult to stand in front of an underfunded independent (who, by the way, shares most of your views, as Parks does Brownley’s) and justify such vast, dishonest expenditures. Very few people want to watch Goliath tear David limb from limb … and independents need to remind voters of that fact, early and often.

6. Complacency just might bite you in the ass. While Democrats have been tearing their hair out over the Parks threat, Strickland and his fellow Republicans have largely been content to raise money by the truckload, zip their lips and watch the carnage on the center-left. Their assumption has been that a half-decent turnout operation is all that will be required for Strickland to breeze through to the general. They’re probably right. Despite the ideological shift brought on by redistricting, voters in my area have been sending a Republican to Washington for decades, and Strickland is practically a force of nature among local conservatives. But what if flying below the radar doesn’t work out for him? What if the Brownley-Parks battle has concentrated interest so greatly on that center-left of the spectrum that both candidates’ supporters beat Strickland’s to the polls? It’s not likely, but it’s a possibility — and it’s even more of a possibility because…

6. Complacency just might bite you in the ass. While Democrats have been tearing their hair out over the Parks threat, Strickland and his fellow Republicans have largely been content to raise money by the truckload, zip their lips and watch the carnage on the center-left. Their assumption has been that a half-decent turnout operation is all that will be required for Strickland to breeze through to the general. They’re probably right. Despite the ideological shift brought on by redistricting, voters in my area have been sending a Republican to Washington for decades, and Strickland is practically a force of nature among local conservatives. But what if flying below the radar doesn’t work out for him? What if the Brownley-Parks battle has concentrated interest so greatly on that center-left of the spectrum that both candidates’ supporters beat Strickland’s to the polls? It’s not likely, but it’s a possibility — and it’s even more of a possibility because…

7. Voters still don’t quite know what to make of all this. Again, I don’t have any polling to back this up, just lots of anecdotal evidence based on conversations with friends, neighbors and acquaintances. But while we Californians voted open primaries into existence two years ago, many voters don’t seem to have processed the consequences of that vote, or to have adjusted their behavior accordingly. Heck, many voters clearly aren’t aware that CA-26 is no longer a safe GOP district — how can one expect them to understand how much more important their votes are in an open primary?

Of course, for many voters who don’t pay too much mind to the early stages of a race, the run-up to a traditional primary is often just noise. But I continue to be astounded by the disconnect between the attention this race has drawn nationally and the blasÁ© attitudes of so many folks locally. A friend of mine calls this the ”So-Cal Bubble” — a me-first focus among denizens of the sunny Southland that tends to block intellectual stimuli (politics, non-Hollywood developments in the culture, books more complex than Fifty Shades of Gray, etc.). Still, the stakes in this open primary are considerably higher than they used to be — particularly for Democrats who have slept through the last five months, assuming that somebody with a (D) will appear on the November ballot.

The consequences of such disinterest may cut either way on Tuesday. Those Democrats, of course, might get a nasty surprise — but so might Republicans, who probably have received a few phone calls from Strickland’s volunteers but can be forgiven for assuming their boy has a November ballot line in the bag. (I have one friend who, politically attuned though he is, believed that Republicans will receive their own special ballot that only allows them to vote for Strickland.) As for Parks, her biggest concern as the campaign heads toward Tuesday must be that voters who aren’t registered as Democrats or Republicans will be unaware that they’re even allowed to vote in the primary. Getting to the general as an independent is a big lift, no matter what the circumstances; Parks knows that, despite her popularity, she would have a much better chance of pulling this off in two or four years, when independents (and moderates from both parties) have a better understanding of how the new system works and are more likely to turn out for someone like her.

8. I still don’t know what I’ll do on Tuesday. I know for a fact that I won’t be voting for Brownley; I simply can’t reward the million-dollar hatchet job that she, the DCCC and other elements of the liberal coalition have performed on Parks. But I’m still unclear for whom I will pull a lever (or, more likely, connect a broken line) next week. Will it be Parks, whose policies and moderation I respect even if I don’t always agree with them — and whom I would like to see stick a (metaphorical) jagged pole up the DCCC’s keister? Or will it be Jess Herrera, the Oxnard harbor commissioner who represents old-line, New Deal Democratic values, and who has proven himself entirely qualified to represent us both professionally and temperamentally — yet who has next to no chance of advancing to November?

8. I still don’t know what I’ll do on Tuesday. I know for a fact that I won’t be voting for Brownley; I simply can’t reward the million-dollar hatchet job that she, the DCCC and other elements of the liberal coalition have performed on Parks. But I’m still unclear for whom I will pull a lever (or, more likely, connect a broken line) next week. Will it be Parks, whose policies and moderation I respect even if I don’t always agree with them — and whom I would like to see stick a (metaphorical) jagged pole up the DCCC’s keister? Or will it be Jess Herrera, the Oxnard harbor commissioner who represents old-line, New Deal Democratic values, and who has proven himself entirely qualified to represent us both professionally and temperamentally — yet who has next to no chance of advancing to November?

Here’s the last lesson of the open primary, at least for open-minded voters: The new system will force us to recalibrate the balance we strike between the qualities of an individual candidate and the ideological values of the party to which we gravitate. The Democrat in me wants to, let’s face it, vote for a Democrat — I want my liberal values represented in Congress (for once), I want my district to go from Red to Blue, and I want John Boehner to have more time for tanning and his party to return to the wilderness, where their lack of civility and compassion won’t hurt the rest of us. But, even notwithstanding the DCCC’s atrocious recent behavior, I can’t warm to Brownley — she seems the epitome of post-1968, something-for-everyone, special-interest liberalism. I like Herrera personally, I like his focus on the working class, and a vote for him would at least represent a clear, unequivocal expression of my personal values.

Yet Parks’ candidacy is compelling. Part of me figures, if I voted to create open primaries and nonpartisan redistricting, shouldn’t I reward a moderate candidate who wants to take advantage of the benefits those changes provide for independents? If I’m sick to death of partisans on both sides who refuse to compromise and accomplish precious little, shouldn’t I help throw a spanner into the works? And frankly, if Parks has a real shot at advancing while Herrera doesn’t, shouldn’t the message I want to send to the Democratic Party also involve backing a potential winner?

So I’m confused, and I’ve got just four days to figure it out. Help me out in the comments, if you feel like it, and I’ll be back next week to tell you how it all went down. In the meantime, maybe this will help me make up my mind.

[youtube id=”sryExlsWRMM” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Comments